A Carnival Comedy: Lost and Found

L'EBREO / THE JEW...

The following quotes are from the unpublished book, CARNIVAL BLOOD.

Chapter One: A TALE OF TWO MICHELANGELOS

"When we cross the threshold of the Casa Buonarroti, the spirit of the place envelops us. We wander through opulent yet intimately-scaled spaces—gray stone, dark wood, muted frescoes, shadowy recesses, sporadic bursts of color and gilt. Exquisite taste hovers on the edge of eccentricity, with curios heaped in every corner. Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger dedicated much of his life and income to the new palazzetto. He also amassed a spectacular collection of his great-uncle’s sculptures and drawings, and established an archive for the family papers—his own included."

.webp)

"On the piano nobile, Michelangelo the Elder holds sway, more than four hundred years after his death. Life-sized in white marble, he dominates the imposing central hall, portrayed as a brooding genius by the sculptor Antonio Novelli"

"Whose story are we following, here in the Casa Buonarroti: Michelangelo the Elder’s, Michelangelo the Younger’s or both at once? The first Michelangelo was a force of nature—uncouth in appearance, harsh in manner, difficult and headstrong at best. The second Michelangelo was a polished courtier, an accomplished litterateur and something less than a genius—a different man in a different time."

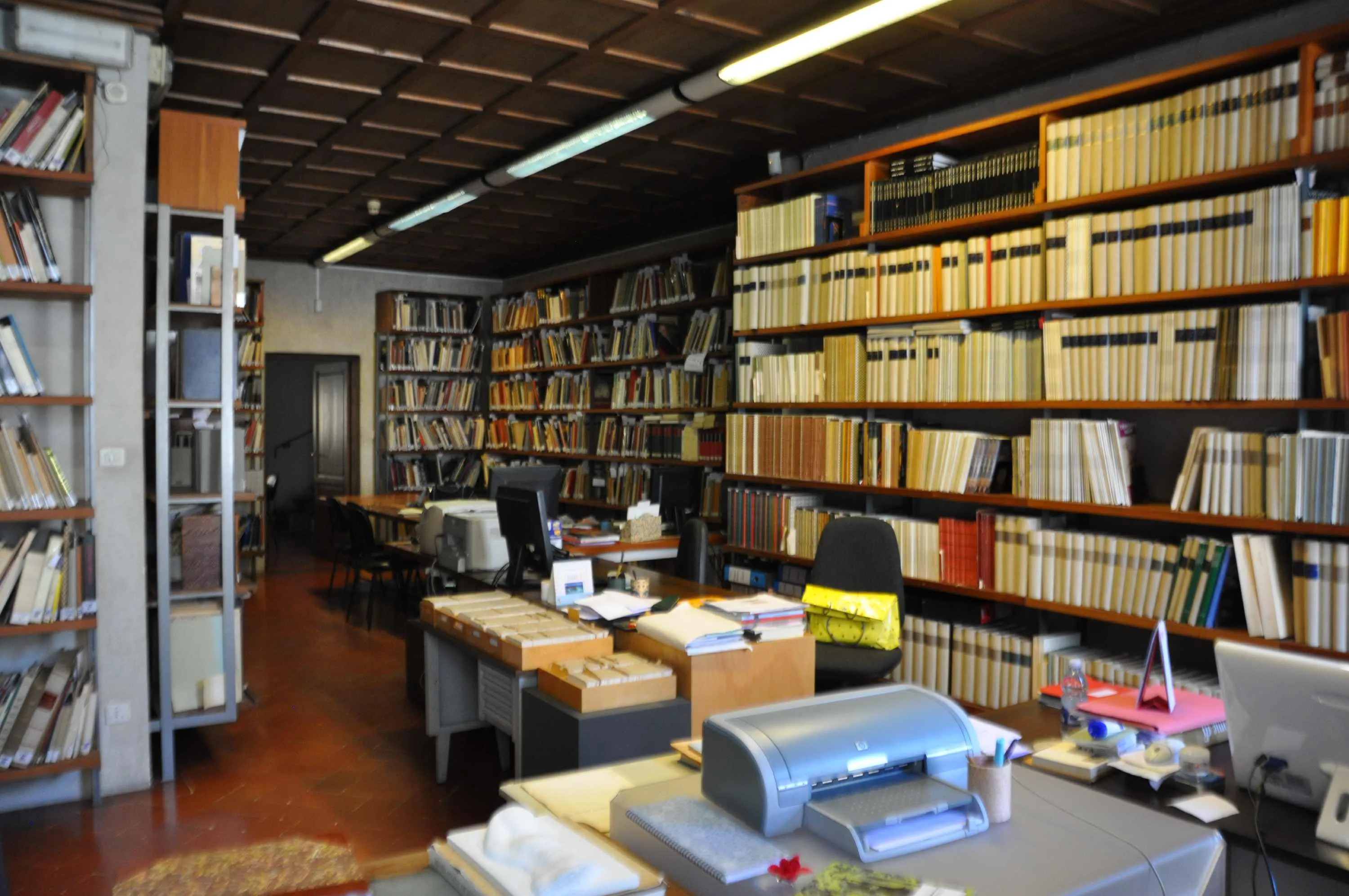

"In the Casa Buonarroti, the family archive awaits—high above the piano nobile, on the third floor. There we find the papers of Michelangelo Buonarroti the Elder (1475-1564), painter, sculptor and architect; the papers of Filippo Buonarroti (1661-1733), pioneer of Etruscan archeology; the papers of another Filippo Buonarroti (1761-1837), utopian socialist and political revolutionary, and—somewhere in the middle—the papers of Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger (1568-1647), poet, playwright and courtier."

"Michelangelo the Younger was a tireless networker, in touch with almost everyone who mattered in late sixteenth and early seventeenth century Italy...We see his hand more or less everywhere at the Medici Court, but in the realm of the theater above all. The princes with whom he exchanged letters were also the patrons of his plays. The musicians composed and performed his songs and orchestral accompaniment. The artists realized the costumes, sets and special effects—while also decorating the Casa Buonarroti."

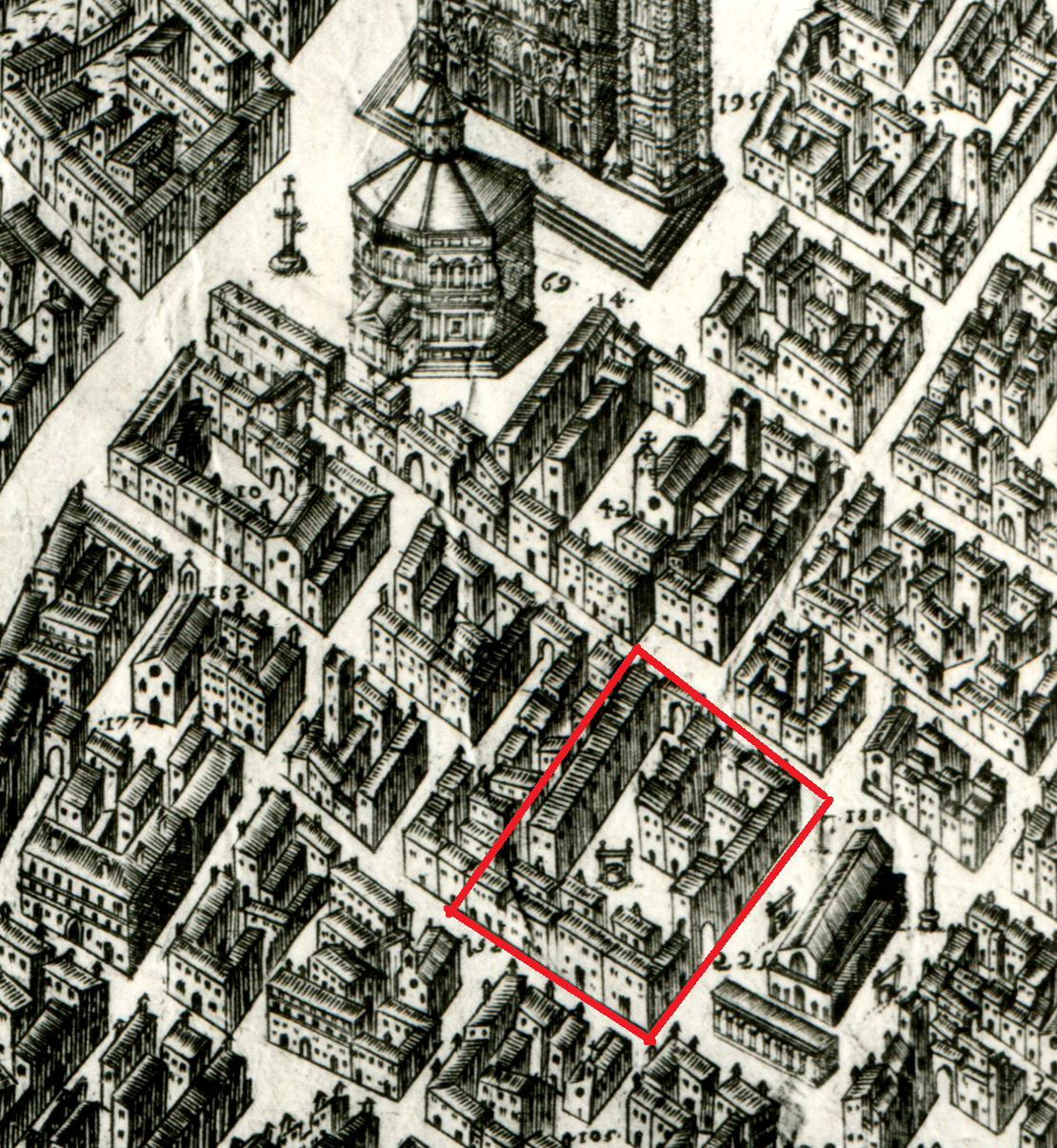

"When we open a volume of Michelangelo the Younger’s writings, we plunge headlong into the author’s life and times. One allusion leads to another, taking us through the bustling streets of late Renaissance Florence, the gilded salons of the Medici palaces, the shadowy precincts of the Casa Buonarroti and even the narrow byways of the local Ghetto."

"Scarcely 500 Jews lived in the Tuscan capital in Michelangelo the Younger’s day, among 60,000 Christians. Still, they were an inevitable feature of local life. Florentine bargain-hunters scoured Ghetto shops for 'Jewish deals' and visited Jewish money-lenders to borrow on the sly. On occasion, Christians might even develop relationships with these intriguing strangers, usually of a business nature, but sometimes veering into the realm of Hebrew language and Hebrew culture, including Kabbalah and the occult."

"Why did Michelangelo the Younger attempt an eccentric Jewish comedy for the Carnival of 1614 at the Medici court? I encountered nothing else like it in his 23 volumes of dramatic works."

"In those very years (circa 1610) rich and cosmopolitan Sephardic merchants from the Ottoman Empire were settling in Florence, carving a privileged place for themselves half-in and half-out of the local Ghetto—while pushing aside the resident community of poor and generally downtrodden Italian Jews. With their extravagant garb and foreign manners, these exotic Easterners were grabbing the attention of more or less everyone. Native Christians had always obsessed over Jews and their doings, but never had they been so visible, so varied and so potentially amusing."

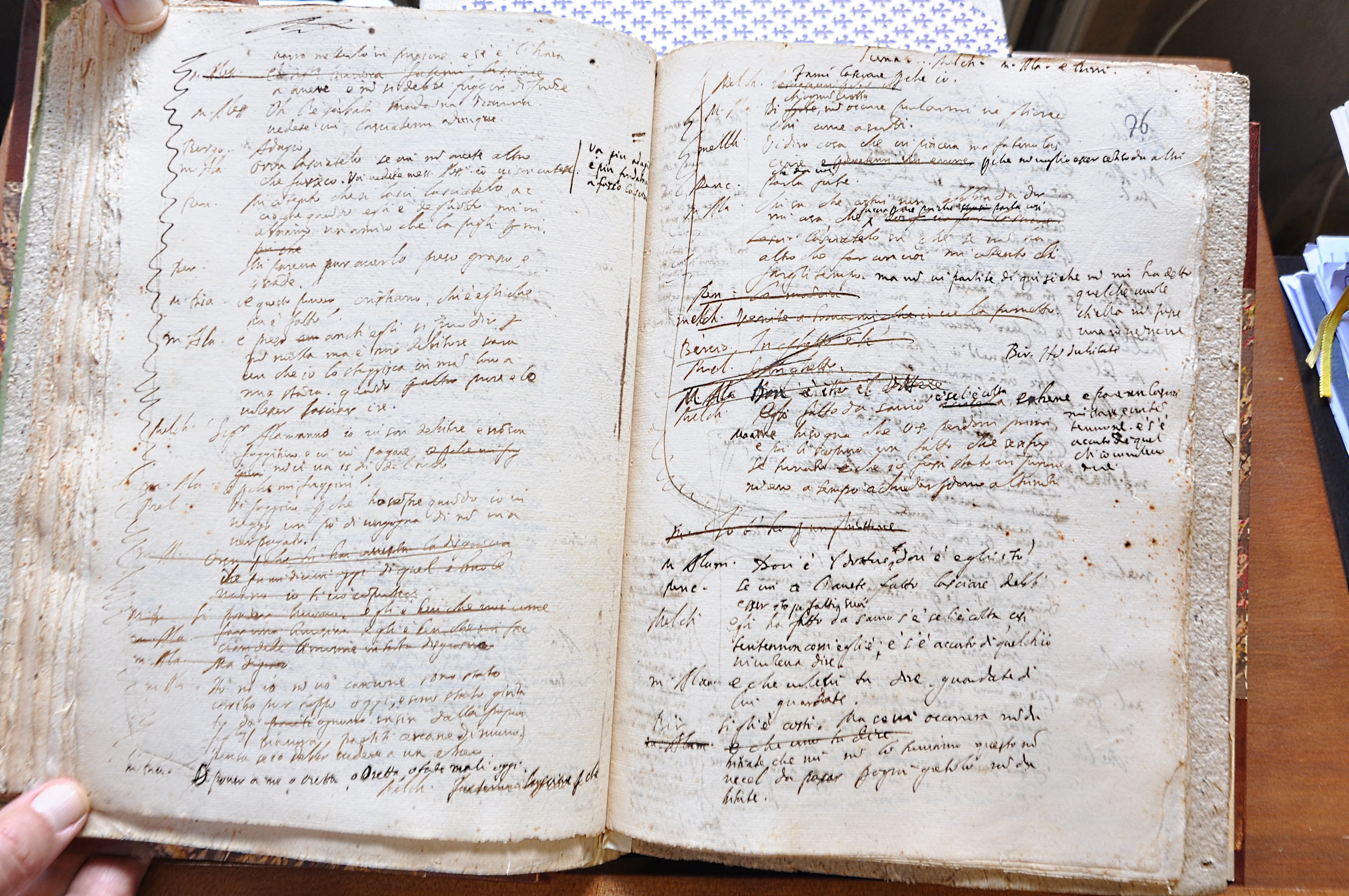

"As the manuscript of L’Ebreo came into focus, I saw Hebrews emerge before my very eyes—in the text, in the margins, in the additions, in the deletions and between the lines. First, I picked up on the back-chat between Federigo (a Christian marriage broker) and Ambrogio (a Christian lawyer in Levantine Jewish disguise).....Then there was the Carnival context."

%20edit.webp)

"Ambrogio: But where are we going to find someone who can pass himself off as a Jew?

Federigo: Don’t worry! Florence is full of people who are more like Jews than Christians. So, let's give this some thought. I want to try those hole-in-the-wall taverns in Messer Bivigliano's Alley where all the foreign charlatans and hucksters and buskers hang out. But wait! This is Carnival! Just walk out the door and we’ll trip over masqueraders of every size, shape and color, imitating everyone you can think of. We might even stumble upon a real Levantine Jew. Wouldn’t that be nice?!"

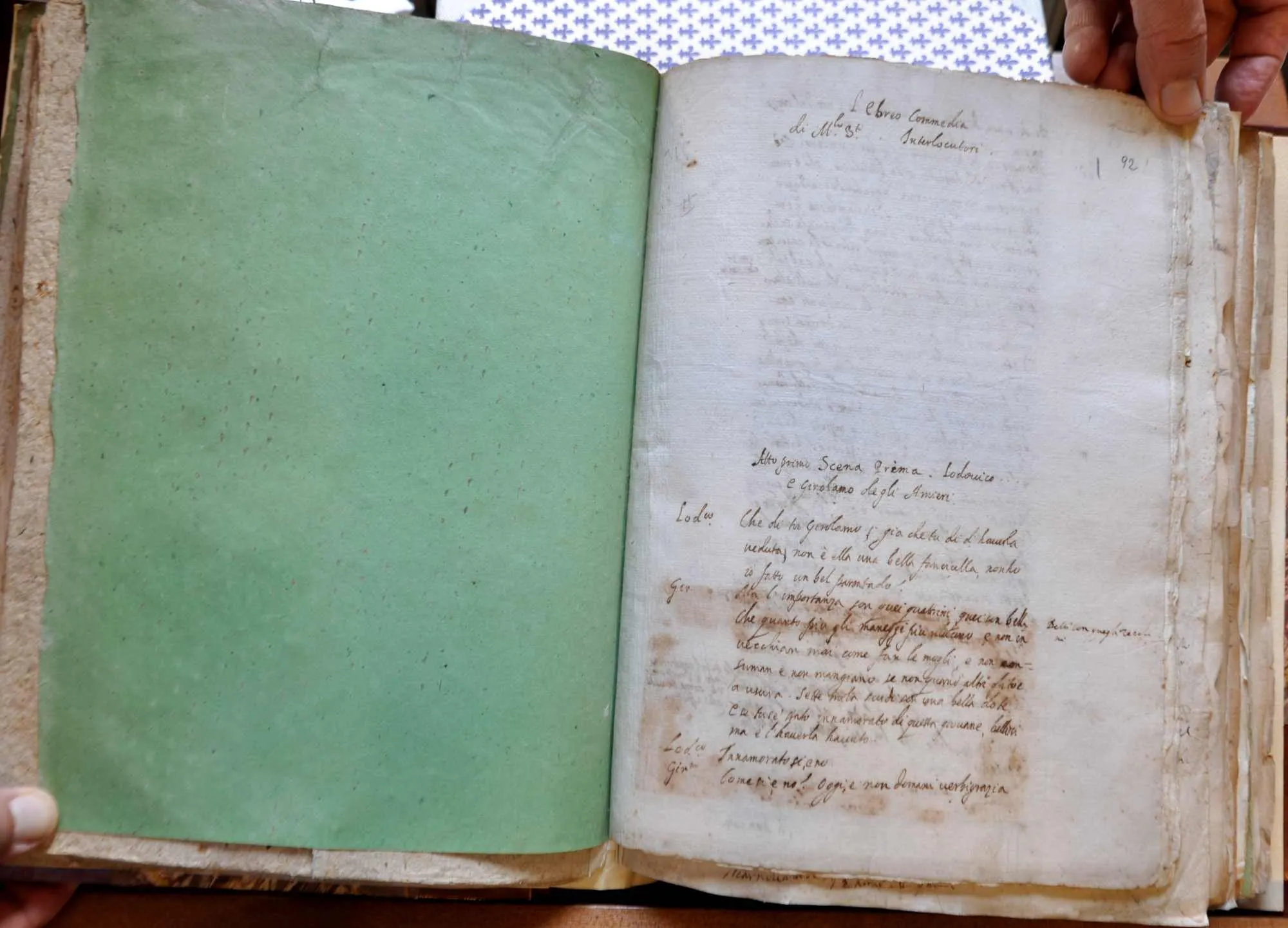

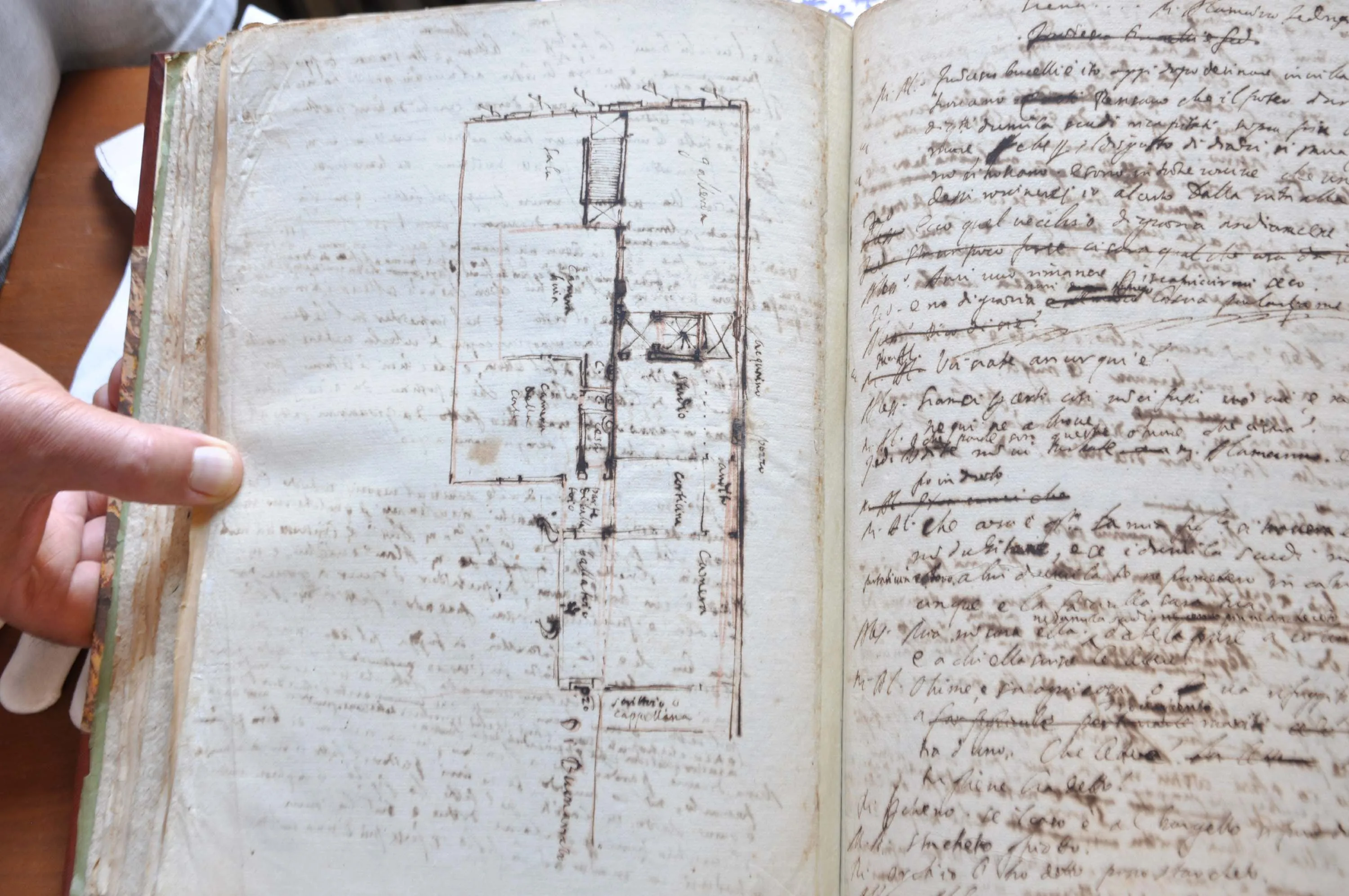

"'Finito? Finished?' What could Michelangelo the Younger possibly mean? “Rough draft” didn’t even begin to describe it! A wriggling mass of scratch-outs and rewrites, marginal notes and pasted-on scribbles. More than a hundred sheets—two hundred sides, front and back—of an unruly work-in-progress. Obscured by the slow burn of acid ink and layer upon layer of decaying restoration."

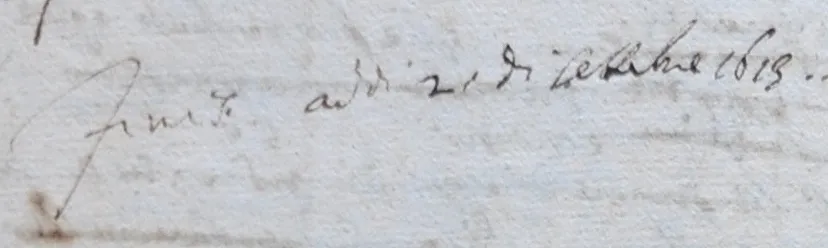

"L’Ebreo was a Carnival comedy and by September 21, 1613 the annual festivities were approaching fast—beginning on January 6, 1614 (Epiphany) and ending on February 11, 1614 (Martedì Grasso or Mardi Gras; the day before Ash Wednesday and the beginning of Lent). Michelangelo the Younger had four months to generate a viable script and move it through production. Was that remotely possible—I wondered—considering the chaotic screed that he left behind?"