Carnival Blood

L'EBREO / THE JEW...

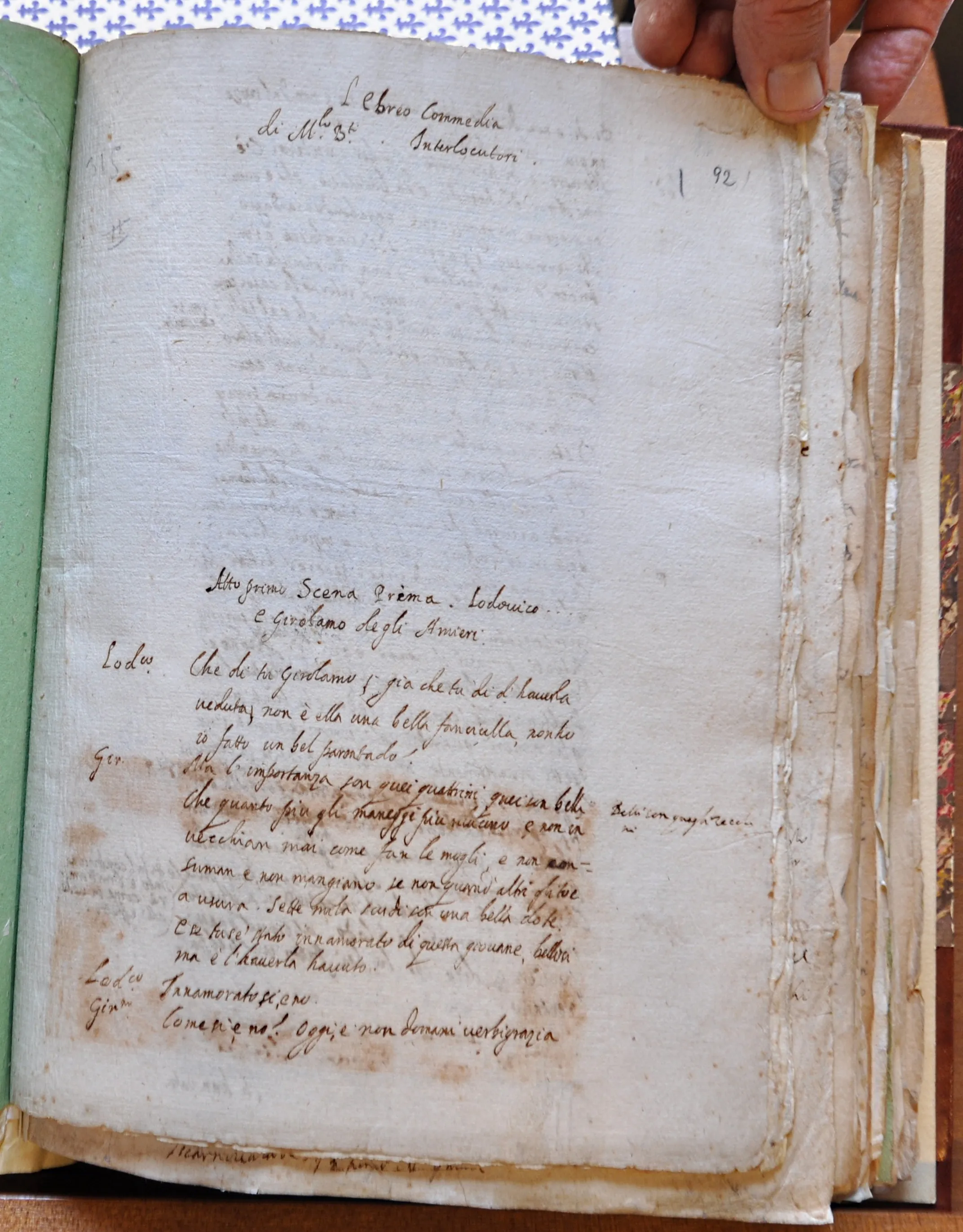

A rollicking Jewish comedy was the last thing that I expected to find when I set foot in the ancestral home of the Buonarroti family in Florence—especially one conceived for the annual Carnival at the Medici Court, especially one written by the great-nephew, heir and namesake of the Divine Michelangelo.

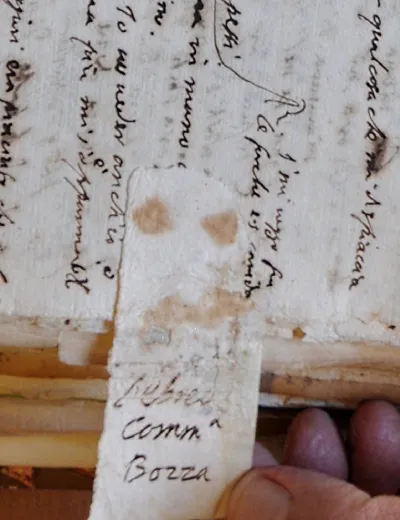

Before I knew it, I was launched on a tumultuous journey—alternately terrifying and absurd—to places I had never even imagined. Then years later, I emerged with the deeply personal and perhaps unpublishable book that I needed to write: Carnival Blood. Also, a hard-won transcription of Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger's very rough draft of a Carnival comedy, L'Ebreo / The Jew. Also, a free-wheeling adaptation of that same play (in English).

Purim Shpiel, anyone? If you are looking for a piece that is crazy fun, easy to stage and a deep dive into both the Jewish past and the Florentine Renaissance, L'Ebreo / The Jew is yours for free. Just get in touch! I look forward to helping however I can.

NOTE: The preceding Chapter 3, BLOOD RITES, features a disconcerting confrontation with a local man in the Northern Italian city of Trent, infamous site of devastating Blood Libel trials and executions in 1475. That is where I pick up, here in Chapter 4, JEWS AS JEWS.

JEWS AS JEWS?

“It wasn’t about Jews. Not really.” His voice was oddly flat. “Not Jews as Jews, I mean to say.” The silence grew, second by second.

“Oh, I see!” I gave him a searching look. “What was it about—really?”

In ancien régime France, they called it l’esprit de l’escalier (the spirit—or boldness, brilliance, daring—of the staircase). It encapsulates all of the decisive, game-changing replies that eluded us during a (typically failed) meeting, then burst forth magically, as soon as the door hit us in the back. Trepverter (step words) is a close Yiddish variant, less grand but disarmingly homespun. I always liked the instant image of a poor schlub (cognate: slob), sputtering uselessly while stomping down the stairs and out.

“Oh, I see!” That was only one of the many retorts that I spared Antonio—right there, in front of the train station in Trent—and as far as “step words” go, it was probably the least sarcastic of the lot. At that moment, truth be told, I totally choked. Maybe I was shell-shocked, arriving in a perfectly pleasant but utterly cursed city for the first time? Maybe I was afraid of his answer?

“What was it about—really?” Trent 1475, the Blood Libel and 19 Jews burned at the stake? For most of my life, I have been wandering through ex-ghettos in Italian towns and villages—places where Jews used to live and occasionally still do. Sometimes, when I can’t avoid it, I come out of the shadow, “Well, I’m Jewish, you know.” Then I track the usual non-response—a quizzical furrowing of the brow, a fleeting smile and a sudden eagerness to talk about anything else.

Now and then, there is an “Antonio moment”—a tiny explosion that comes and goes in the blink of an eye, cracking the surface of daily life and revealing the ancient realities beneath. Over the years, I have learned to read a whole language of flickering signs and signals, visceral reactions seldom acknowledged by the actors themselves.

“What was it about—really?” Jews as Jews, or not? In Florence, Rome and Trent. In 1475, 1613, 1945 and now. Who did Michelangelo the Younger have in mind, when he inscribed L’Ebreo (The Jew) at the top of his play? What do Italians think today, when I call myself—that?

FERRARA

I wasn’t looking for Jews in Ferrara forty years ago, although there are still some to be found—a remnant of the thousands that resided in the Italian Jerusalem before the papal annexation of 1597, the institution of the Ghetto in 1627 and (within living memory) the fatal savagery of the fascist era. I had, of course, read Giorgio Bassani’s bitterly nostalgic novel, The Garden of the Finzi Contini (1962) and seen Vittorio de Sica’s luscious film (1970), recording the not-quite-final dissolution of that very community. But I was an art historian back then, so I was on an art historical quest—looking for School of Giotto frescoes at Sant’Antonio in Polesine, an ancient convent of Benedictine nuns under the venerable patronage of the Este family, one-time lords of Ferrara.

The sisters were strictly cloistered, so I found a mossy courtyard, an arched portal and a heavy wooden door with a tiny grill at eye-level. “Can I see the frescoes?” I whispered—something about the place made me whisper.

“Welcome! Welcome!” a wavering voice replied. “But not now. Please! I’m alone. The sisters are in the chapel.” The hatch slid shut.

“What would be a good time?” I rang again and her voice still trembled. “Oh? Oh? I don’t know! Mother will arrive in twenty minutes.”

So I circled the courtyard and ventured into the damp garden while studying my watch. “Welcome! Welcome!” The second voice came from a very different place than the first. Then the door swung open and I found myself facing the most supremely charming woman I have ever met. Ageless and tall by nature, she seemed even taller in her traditional habit—tunic, coif and the works.

“So kind of you to come!” I could imagine her lady ancestors receiving guests in drawing rooms and ballrooms since time out of mind. “How might I help?”

“Giotto,” I began. “Frescoes,” I added.

“Of course!” She set off at a brisk but unhurried pace and I followed. The other sister brought up the rear, her hands folded, her mouth twisted in a worried frown, her glance darting in all directions at once. The corridors were sparkling clean and the windows shining, with the strangely muted aura of establishments of that sort. We entered a gothic chapel. School of Giotto, yes. Early 1300s. The Life of the Virgin. The Infancy of Christ. Then the Passion of the same.

“Now the sacristy,” Mother announced, ushering me into an opulent boudoir bedecked with flowers and birds—decorative fantasies of the most worldly kind. My double-take was entirely expected and she acknowledged it with a flawless laugh. “One of our sisters, centuries ago, insisted on bringing her bedroom with her. What can you do?” She shook her head and crossed herself. “After she died, we made it into our sacristy.”

“And the Blessed Beatrice d’Este. You know her story?” Actually I didn’t, I confessed. Beatrice was the founder of the convent, daughter of Azzo VIII d’Este, Lord of Ferrara. After her death in 1262, she was buried right there in the cloister. Surely I wanted to see her tomb? “Yes, of course,” I replied, not knowing what else to say. So, she launched a long and intricate tale regarding the tomb and its many miracles.

It was set in a corner and covered with a sheet of lead, alarmingly soft to the touch. When she lifted it, I would be able to see—well, I wasn’t quite sure what. Drops of liquefied something with marvelous properties. The Italian phrases were running way too fast.

Suddenly she stopped—missing a beat for the very first time. “Oh, are you Catholic? I hadn’t thought to ask.” And I was facing the “Well, I’m Jewish, you know” moment to end them all.Mother was a great lady, bred in the bone, and she had been handling “situations” for much of her life. But this one eluded her, for a few seconds at least. I saw a wave of panic spread across her face, then instantly she was back in control.

“Oh, but you are a faithful Jew, of course?” “Well, I try to be.” She made a perfect save and I offered the expected response. So, she lifted the lead sheet and showed me drops of something. I counted to ten—waiting for her to replace it—and we were ready to move on.

Convent sweets and herbal tea were served in the parlor, with polite small-talk about Ferrara and art. Meanwhile, she kept a close eye on the other nun, who was in evident distress and—I suddenly realized—not entirely sane.

So, I took my leave and my hostess saw me to the door, clasping my hand and kissing me on both cheeks. “Thank you!” I said, “Thank you!”, then I ran out of words. She smiled, I smiled and the door closed.

CENTO

The next morning, I set out for Cento—only 19 miles (30 kilometers) from Ferrara but a slow fifty minutes by bus. It was one of those dusty places where the train doesn’t go anymore.

“Hello! Are you Jewish?” Those were the first words that I heard, in what passed for a bus station, spoken by a certifiably crazy man, or so it seemed. He was old—seventy or eighty, at a guess—with a pronounced limp, wearing a dark smock of some kind.

“Jewish? Well…yes.” I barely had time to wonder.

“Come!” he nodded, grabbing two heavy bundles of newspapers and magazines that had arrived on the same early-morning bus. I tried to snatch one of them but he shook his head. Then he shuffled his way to an old-fashioned newsstand in the nearby square, lurching weirdly from side to side.

He arranged his acquisitions with painstaking care. Had he simply forgotten that I was there? “So, that’s okay!” he announced, without turning around. Then he circled the little structure and stationed himself inside.

Through an opening festooned with football pennants and dangling toys, he handed me a thick black binder—but quickly snatched it back. Then he started flipping pages, hastening past murky photos from who knows when.

“That’s in Israel.” He held up a dramatically shadowed sepia rendering on thick paper, featuring an elaborate aròn (ark). “These are in Ferrara now.” He showed me a disassembled heap of carved wooden fittings. “Lots of Jews in Ferrara!” He smiled.

“We still have two families here.” He rattled off a pair of names that I couldn’t catch—leaving me to deduce that “two families” meant “three people”, no more and no less.

“In Cento? You and them?” He nodded, “Yes.”

“Life is good. Baruch HaShem (Blessed Be The Name).” That was the gentle lead-in to a terrible story that he told in an utterly casual voice, as if it all happened to someone else. At the age of fifteen, he was arrested by the Germans—who tortured him, severed the tendons of his legs and abandoned him in the hills. He was supposed to die, but didn’t, and somehow made it home.

“But life is good, Baruch HaShem!” He touched his head. “I lived to have gray hair. I’m fifty now, you see!”

“Baruch HaShem,” I echoed, while doing the math. Fifty? It added up—but I would have given him seventy-five, if a day.

Cento feels like a toy town, when horrible things aren’t happening. There’s an arcaded piazza, a half-dozen streets, a miniature castle and masses of baroque painting—mostly by Giovanni Francesco Barbieri (1591-1666), Cento’s most famous native son. Known as “il Guercino” (The Squinter), he spent much of his life right there, while working for great patrons throughout Europe.

There are major Guercinos in the Municipal Picture Gallery but my plan was to begin at the end—at his self-created burial chapel in the Church of the Rosary (Chiesa del Rosario). A middle-aged woman was seated at a small table just inside the door, with an assortment of pamphlets, candles, medals and rosaries, plus a clipboard with a sign-up sheet.

“Prego?” Can I help you? I came to see Guercino, I explained. She laughed and tugged down the corner of her eye, miming a little “squinter” joke. Then with a practiced flourish, she pulled a bunch of keys from the pocket of her smock and led the way. The shallow chapel was richly laden with decoration, including a lavish altarpiece of the Crucifixion and three ceiling panels—all by the man himself.

“His eye! That’s why they called him Guercino,” she repeated the gesture, “but his real name was Giovanni Francesco Barbieri. How do we know?” She gave me a girlish wink.

“You tell me.” And she did—pointing to the three stucco-framed pictures on the ceiling. Saint John the Baptist (Giovanni), Saint Francis of Assisi (Francesco) and God the Father. She raised her eyebrows.

“God the Father?” I knew my lines. “Why Him?”

“Because God the Father has a beard!” Barba means “beard”. Barbieri means “barbers”. So, Giovanni Francesco Barbieri. Get it? I did.

Suddenly, the whole thing fell apart—the amiable silliness. She went running off, without a word, and returned with her clip-board and a handful of rosaries.

“These are our own special Chiesa del Rosario rosaries. You can only get them here! Every evening, we…”

Whatever was coming, I needed to nip it in the bud. “Well, I’m Jewish, you know.” Sometimes, there’s a lot to be said for the simple truth.

A tall and rather stout woman, she seemed to deflate before my very eyes. She gave me a stunned look—not hostile, merely stunned. “What are you doing here? Why did you come back?”

“To look at Guercino,” I explained. “I’ve never been to Cento before. And I’m catching the bus to Modena tonight.”

She shook her head fiercely, then smiled. I saw that the moment had passed. “You can send these to your mother and your grandmother. Maybe you have a sister too?” I handed her far too many lire notes and almost—but not quite—ran for the door.

On the sidewalk, I pulled out my guidebook, while stuffing three rosaries into a back pocket. Time for Cento ebraica. Jewish Cento. I had gone off art—for that day, at least—and I didn’t need to see another Guercino for the rest of my life.

On the map, there was an area marked “Ghetto”, just past the main square—small in itself, but still a significant portion of this undersized town. Cento was the ancestral home of the Disraeli family. Who knew? As in Benjamin Disraeli, Prime Minister of England.

A battered palace faced the narrow street, with a substantial portal in the middle. I entered an ample courtyard in advanced decay, picking my way over the broken pavement. Peeling plaster, crumbling stone and sliding roof-tiles, but also iron balconies, elegant window surrounds and other signs of former state. Two elderly women were doing—something—with a shapeless pile of—I didn’t know what. Their focus was a sturdy table of rough planks on ancient sawhorses, worthy of any museum of rural life.

They looked up from their archaic task—stuffing a mattress with hemp (canapa). A great-niece was getting married, they explained. And mattresses these days? They shook their heads. “And all of this?” I gestured to the ambient wreckage.

“This is where the Jews live!” they replied in unison, in the present tense. Was anyone else camped out there, I wondered, amidst the ruins?

“There’s the synagogue!” they gestured. “There’s the Casa Finzi! There’s the Casa Levi! There’s the Casa Carpi!” Then they started telling stories, thrilled to have any listener at all.

There was such hustle and bustle back then. I couldn’t imagine! Cento hemp (canapa di Cento) was a famous brand. Rope and sacking and whatever else. The Jews were brokers. They knew the landowners. They knew people in the towns. And they lived right here, near their warehouses.

I was talking to domestic servants—Christians, of course—from the homes of long-gone Jews. And for them, those Jewish times were the good old days of their youth. “The old signora was always staring like a hawk when we put away the plates.” A real character, I bet! “Every spring, they made the biggest feast you ever saw, but used old dishes and wouldn’t touch bread!” Passover, of course. “But they did something to the little boys…” Their eyes met and they giggled. “We can’t talk about it!” Circumcision, right?

“So, where are they now?” I looked up at the boarded windows and pitted walls. I could have counted to ten, while waiting for them to return to the present day. “Oh, they’re in Rome!” “No, Milan!” “America, I think!” They had no end of ideas.

In fact, there had been a full-fledged concentration camp at Fossoli, only 27 miles (44 kilometers) away—but I didn’t know that until years later. And from Fossoli, it was four days to Auschwitz, by very slow train.

NIZZA MONFERRATO, SPOLETO AND ROME

Jews as Jews? Jews as not-Jews? Jews as whatever else? In Guercino’s church in Cento, did the sacristan really imagine that my sister, mother or grandmother would welcome the gift of a rosary—however “special” it might be? Maybe it was the old male/female thing (we were back in the 1970s, after all.) Women go to church and say the rosary, while men have strange ideas—becoming communists, freemasons, sports fans and even Jews.

“Well, I’m Jewish, you know!” How many times have I announced this, to the utter bewilderment of even my closest friends? I remember an Easter weekend—way back when—in Nizza Monferrato, a small town about 55 miles (88 kilometers) from Turin. There were five of us, all in our late-20s. Except for me, everyone was Italian, a recently qualified medical doctor and Catholic by default.

In Italy, “Easter Communion—or not?” is the preferred seasonal drama. So, I could follow the usual declension from “Like hell I will!” to “Let’s just do it already and stop talking!” On the eve of Easter, I found myself at a grim exurban church—off the highway, in the middle of nowhere—watching my friends pop in and out of confessionals. Then they turned to me.

“Well, I’m Jewish, you know!” I laughed, eliciting a rapid flurry of shrugged shoulders and waved hands. What was my point, anyway?

“Well, I’m Jewish, you know!” I repeated, wondering what else to say.

A newly-minted cardiologist—a no-nonsense type—jumped in, diffusing the cluelessness. “So, we can get out of here?” Yes, we could, so we did. And that was that.

Then I remember the absurdist drama of my passport case, a notably handsome item in black leather. I was visiting a friend in a famously picturesque town in Umbria—decades ago—and I left my passport on the kitchen table with my traveler’s checks, on my way to the bank.

“Really nice!” my friend Francesca observed. Italians have an eye for leather accessories.

“My godmother gave it to me,” I explained, “when I got my first passport and went abroad.”

“Your godmother!” Signora Margherita, Francesca’s mother exclaimed. Absolute salt of the earth, raised on a small farm outside town. “She held you at your baptism!”

“Baptism?” I laughed. “Well, I’m Jewish, you know!”

“Still, you’re baptized of course!” Signora Margherita insisted and I shook my head.

“You’ve got to translate!” She spun around, grabbing her daughter by the shoulders. “He didn’t understand!”

“He’s Jewish!” Francesca tried to help.

Signora Margherita started wringing her hands. “Yes! Yes! Yes!” I could see her spiraling through a thousand years of peasant superstition, while the spirits of the non battezzati danced in the air.

Have Jews ever been real to anyone but themselves? Have Italians ever expected them to make concrete sense? Ranging through the past, I find myself bumping into “not Jews as Jews” at every turn, especially at Carnival time. I recall a droll scene in Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger’s L’Ebreo (The Jew).

Ambrogio: But where are we going to find someone who can pass himself off as a Levantine Jew?Federigo: Don’t worry! It's not as if Florence wasn't full of people who are more like Jews than Christians! Let's give this some thought. I want to try those hole-in-the-wall taverns in Messer Bivigliano's Alley where all the foreign charlatans and hucksters and buskers hang out. But wait! This is Carnival! Just walk out the door and we’ll trip over masqueraders of every size, shape and color imitating everyone you can think of. We might even stumble upon a real Levantine Jew! Wouldn’t that be nice?

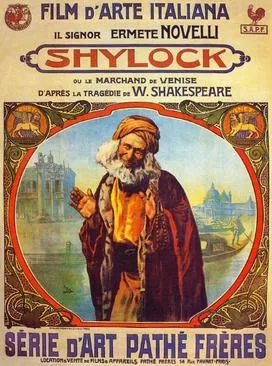

Just scratch the surface and we are all Jews, with a nudge and a wink—so now you see them and now you don’t. In the autumn of 1613, Michelangelo the Younger was composing L’Ebreo for the coming Carnival, but Shakespeare had already gotten there a decade or two earlier, in The Merchant of Venice (written around 1596-99).

Portia: Which is the Merchant heere? and which the Jew?

Duke: Anthonio and old Shylocke, both stand forth.

Wise Portia pretends that she can’t tell the difference, which she certainly could, since Antonio was dressed as a Christian gentleman and Shylock in a long gabardine. We can imagine Shakespeare’s spectators—and Buonarroti’s—elbowing each other and laughing in merry complicity.

And then, there are the opening lines of a comedy, conceived for the Roman Carnival of probably 1644.

Jews: Your Lordship, we are here to serve you.

Coviello: May a thousand plagues take you!

A sudden burst of Jewish foolery—setting the stage for who knows what?

Jews: Pardon our importunity. Again and again, we have gone to Signor Cinthio to ask for our money. And now he sends us to Your Lordship so that you can pay us.

Coviello: It is a sin to help you, beasts that you are! Do you know how many times Messer Cinthio has told me to give you that miserable money? But instead, I was trying to cut you a real break by putting you onto a great deal.

Jews: Excuse our ignorance.

Coviello: Well, now you’ve blown it! Messer Cinthio even wanted to give you permission to drive around in carriages with your women, wear black hats and go visiting palaces and gardens. But like I said, it’s a sin to help you. So, take these four filthy coins and go hang yourselves.

Jews: In that case, we don’t want them, begging Your Lordship’s pardon.

Coviello: Now go see if you can find me another silk cloak, like the one I’m wearing but longer.

Jews: We’ll take care of that.

Exit Jews.

They would have been on and offstage in only three or four minutes—these Christian actors in Jew-face—but that was plenty of time for the usual memes to come tumbling out. We have Jews dunning a debtor for money, Jews peddling old clothes and Jews sent off to the gallows (“iate alle fuorche” in Roman dialect), alluding to the fate of Judas, the perennial arch-Jew. We can imagine this Hebrew rabble in long caftans with their obligatory red or yellow hats, hunching their shoulders and waving their arms, filling out their scant speeches with a wealth of ghetto inflections. They would have worn stylized masks in the Commedia dell’arte mode, with vast hooked noses visible from the last row of seats.

Why Jews? They vanish after this explosive curtain-raiser, never to be seen again—then a whole other play kicks in. We are watching a fast-paced back-stage comedy, focusing on the trials and tribulations of a brilliant but impulsive theatrical engineer named Gratiano. He is staging a sensational Carnival entertainment in a grand Roman palace, art imitating life and all the rest.

Engaging as the concept might be, this particular Carnival entertainment would probably pass unnoticed except for the extreme celebrity of its author. He was Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), the preeminent sculptor and architect of Baroque Rome, serving pope after pope for sixty years. We can, in fact, recognize the irascible Gratiano as a witty caricature of Bernini himself. Since he often acted in his own comedies, he probably planned to play his facetious counterpart, perhaps in the ample theater attached to his palatial home.

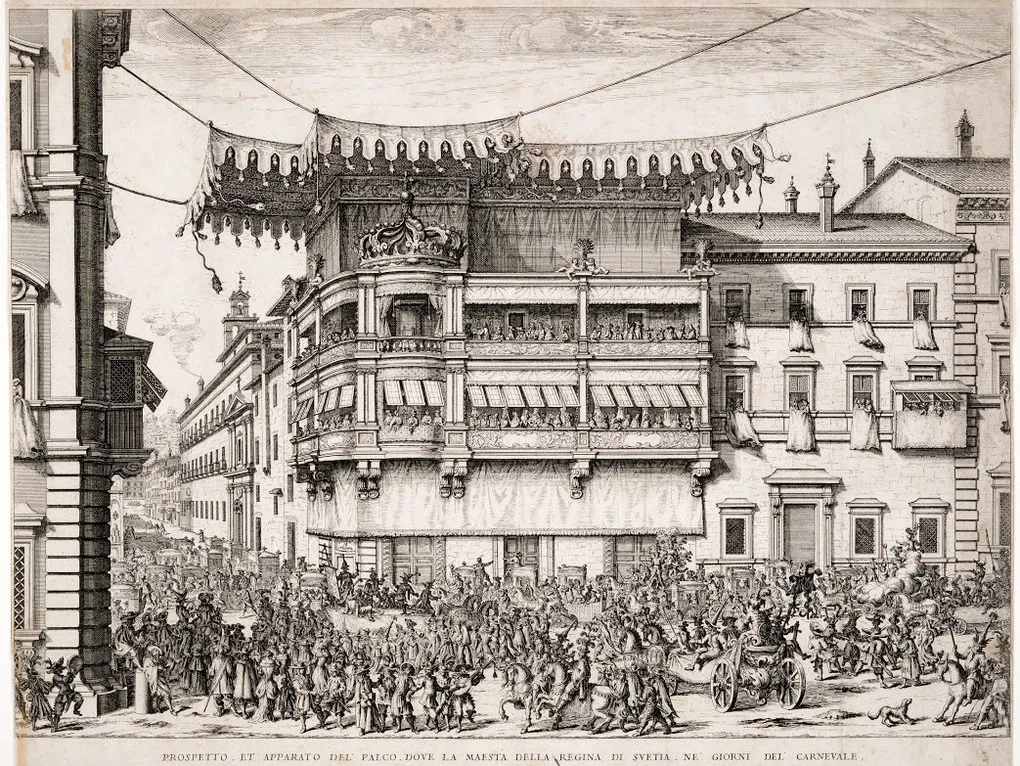

At the time of L’Impresario (The Theatrical Producer)—as Bernini’s untitled comedy is usually known—he was de facto prime minister of the arts to Pope Urban VIII Barberini (reigned 1623-44). So, we are looking at the ultimate insider production, with a renowned public figure cutting loose for his friends and patrons—including cardinals, nobles, papal nephews and foreign ambassadors. Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger visited Rome on various occasions, between 1609 and 1630, hoping to launch a career in the Eternal City. A notable insider in his own right, he was the childhood friend and former college roommate of Cardinal Maffeo Barberini (eventually Urban VIII)—as well as a distinguished writer, a Medici courtier and the great-nephew of the Divine Michelangelo.

In Bernini’s brisk prologue, there was much to entertain the rulers of Rome, who were also the rulers of the Catholic world. Just imagine! You are plowing through the jammed streets of the papal capital in your opulent carriage—with a liveried driver, running footmen and galloping outriders—when you run into another, full of frolicking Jews dressed as Christians. Then you face off with the same ghetto horde, picnicking in your garden or fingering the tapestries in your saloni.

The world turned upside down! The very stuff of Carnival hijinks! But what about the dignitaries who chuckled at Bernini’s grotesque chorus of gentile performers in Jewish disguise? Some of them would have flanked the pope himself under the Arch of Titus on the first day of Carnival, when he received the annual ghetto delegation. Then these princes and princelings hastened to join their cohorts in palace balconies lining the Corso, shouting cheerful jibes at a troop of naked Israelites racing below.

If someone made Bernini’s Carnival comedy into a movie, we would call this raucous curtain-raiser an “establishing scene”—signaling the time, the place and whatever else. But who are these fake Jews anyway and why are they suddenly in our face? Maybe Bernini’s Hebrews are just a sign of the season—I found myself wondering—a fleeting festive touch? Like Halloween pumpkins, Thanksgiving turkeys or Santa Claus?

How about Easter Bunnies? I caught myself in the nick of time—but outrageous as that sounded, it was at least partially true. The Killers of Christ were never far from anyone’s mind, in the capital of world Catholicism, during the tumultuous run from Epiphany through Lent to Holy Week and Easter. There would have been only a meager Carnival without them, since the Jews of Rome were paying for the revelry with their money and their lives.

NOTE ON SOURCES: This includes an update on my reporting from Cento. My original account (above) accurately records my experience on my two visits (several days apart). Then it took me nearly fifty years to discover that I had gotten much wrong—on a strictly factual level, at least.

There are many personal stories in this chapter and decades later, I am still in touch with some of the people involved. Have Italians become more savvy (or less clueless) in the last half century, regarding people with different cultural assumptions than their own—especially those in their very midst? My own sense is that the recentish wave of tone-deaf political correctness has tended to push people even further into incomprehension. Then the (inevitatiblle?) right-wing back-lash made things even worse.

My visit to Cento in the mid-1970s remains one of the most overwhelming experiences of my life, but only recently did I try to lock down the facts. Fortunately, I knew exactly where to begin, with my old friend David Stone, an art historian who works on Giovanni Francesco Barbieri (il Guercino) and has been in and out of Cento for many years. David Stone put me in touch with Fausto Gozzi, retired director of the Municipal Picture Gallery (Pinacoteca Civica). Dr. Gozzi vividly recalled “Bruno who ran the newsstand in the piazza”, the family of mattress-makers (named Tosi) in the former ghetto and the sacristan in the Church of the Rosary (named Rosaria, no less). In fact, Dr. Stone had met Rosaria as well—about ten years after I did—and enjoyed the same story about Saint John, Saint Francis and the beard of God the Father. Dr. Gozzi, in turn, introduced me to Tiziana Galuppi, an historian of Jewish culture and the keeper of many local memories and traditions in Cento.

Dr. Galuppi was extraordinarily generous with her research and recollections, especially regarding “Bruno Alberghini il giornalaio”, the newsagent whom I met at the bus station. Bruno’s story was even stranger and more complicated than I imagined—and not entirely what Bruno had told me first-hand. His mother was a poor widow from the country who went into service with the Jewish Finzi family in Cento, specifically three unmarried sisters Amelia, Bice and Elvira Finzi, who were known for their entrepreneurial skills (they ran a stationer’s shop) and their musical gifts. So, the boy (born out of wedlock) grew up in a Jewish environment, with these three spinsters as surrogate mothers. He strongly identified as Jewish, but was not a full member of the community (by descent or conversion, and never circumcised).

Alberghini qualifies as a “holocaust survivor” by most standards, although the details of his experience remain unclear. While not actually Jewish according to the racial laws of the time, his insistence on an Israelite connection could have attracted the attention of the Nazi occupiers. Also, he was probably homosexual, which would have heightened his exposure. In late 1944 (when Bruno was around 16 or 17), he set out to acquire milk on the outskirts of town and then disappeared without a trace. At the end of the war, Bruno’s sister Adele Alberghini was contacted by the Red Cross and she made her way to Bolzano (near the Austrian border), where she found him in an emergency hospital, in very bad shape. Adele brought him home to Cento, where he was nursed back to health, but with permanent physical—and probably psychological—damage.

During the German occupation, the Jews of Cento (by then, very few) effectively went underground and avoided deportation. Even before his arrest, however, the young Bruno Alberghini had been a protagonist of the Jewish resistance. During the night of November 15, 1943—while fascist forces were descending on Cento—Bruno and a friend entered the synagogue and secured liturgical objects (including the Torah scrolls, with their ornaments) and left them with a priest (who hid them under the high altar of his church) until after the conflict.

Lucio Pardo (former President of the Jewish Community of Bologna) wrote in 2004, after Alberghini’s death about ten years earlier, “For many long years, Bruno Alberghini lived in an apartment in the Ghetto of Cento that belonged to the Jewish Community and he managed a newsstand in the nearby central piazza. He wasn’t Jewish, but still an important resource for historic memories of our presence in that city. He was very proud of ‘his’ community and apparently often thought of becoming Jewish. On major holidays, he was always present in the Synagogue of Bologna, where he kept everyone informed of the state of the Ghetto in Cento. He was a recognizable figure: rather frail, smiling, always greeting people with ‘Shalòm! Shalòm!’ In fact, he adopted that as his name, signing himself, ‘Shalòm Alberghini’.” L. Pardo, “Leone Maurizio Padoa: un ricordo, una presenza”, p.15; http://amsacta.unibo.it/899/1/Pagine12_16_da_atti_del_convegno_Padoa_27012004.pdf“

"Shalòm! Shalòm!” caught my attention, since that is exactly how Bruno Alberghini greeted me two days after my initial visit, when I returned to Cento for a few hours to see the Pinacoteca Civica. He spotted me in the piazza, shouted his greeting and added “You came back! I knew that you would come back!” Once again, he pulled out his black binder of photographs, although I did not suspect his role in the rescue of many of those objects. There is now considerable interest in Cento’s Jewish past, due in large part to Tiziana Galuppi’s efforts, including her book Gli ebrei a Cento: Storia di una Comunità (Cento, 2012).

Ever since my two brief visits to Cento circa 1976, that small town came to occupy an outsized place in my consciousness—assuming a strange non-geographical realty of its own. During the subsequent half-century, I often visited that part of the world, stopping in Bologna, Modena and Ferrara, plus smaller towns like Carpi, Correggio and Mirandola, but obsessively by-passing Cento. In the spring of 2023, I finally overcame this psychological red-lining, meeting up with Tiziana Galuppi and Fausto Gozzi, who were as charming and gracious as I had imagined. The miniature castle and the central piazza were much as I remembered, but the Pinacoteca and the Church of the Rosary were still closed for restoration, structurally compromised during the earthquakes of 2012. While the former Ghetto was spared significant damage at that time, it suffered a modern catastrophe of its own—stripped, scrubbed and partially demolished by property developers. The Ghetto is now a pleaant if unremarkable residential enclave in the heart of town and an evident commercial success, but a distressing lost opportunity on many other levels.

The manuscript of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s carnival comedy is in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. It was long referred to as La Fontana di Trevi (The Trevi Fountain) due to an unrelated notation on the manuscript. See Cesare d’Onofrio, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Fontana di Trevi: Commedia inedita (Rome, 1963). An interesting assessment of this comedy and its performance context is Irving Lavin’s “Bernini and the Theater”, in The Art of Gian Lorenzo Bernini (London, 2007), Vol. I, pp.15-32. This is a fuller version of Lavin’s review of d’Onofrio’s edition, in The Art Bulletin, LXVI, 1964, 568–72. An English-language version of the play was published some years ago, with a more appropriate (if mildly anachronistic) title, Donald Beecher and Massimo Ciavolella, The Impresario (Ottawa, 1985). The relevance of the Jewish opening scene was long overlooked, with one notable exception, Sandra Debenedetti Stow’s “Parole in Giudaico-Romanesco in una commedia del Bernini”, Lingua Nostra, Florence, vol 31, 1970, pp.87-89.

Thinking Out Loud

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.