GARIBALDI & GOLDBERG LAND IN SICILY: A Jewish View of the Italian Risorgimento (Part 1)

CONTENTS:

(1) "GOLDBERG, MEET GARIBALDI!"

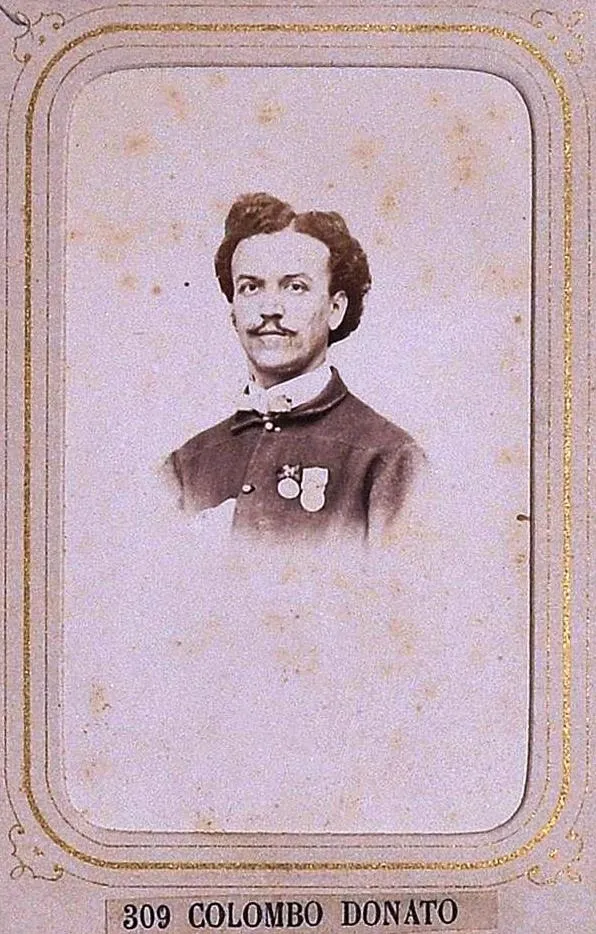

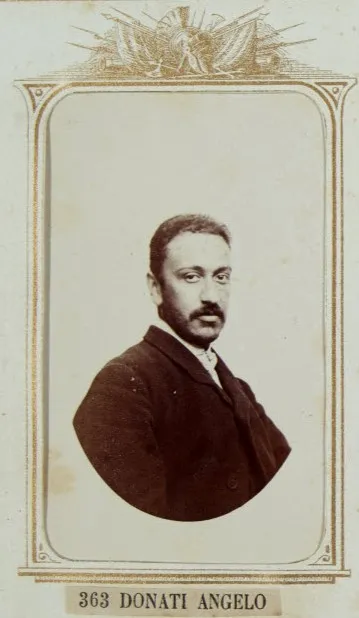

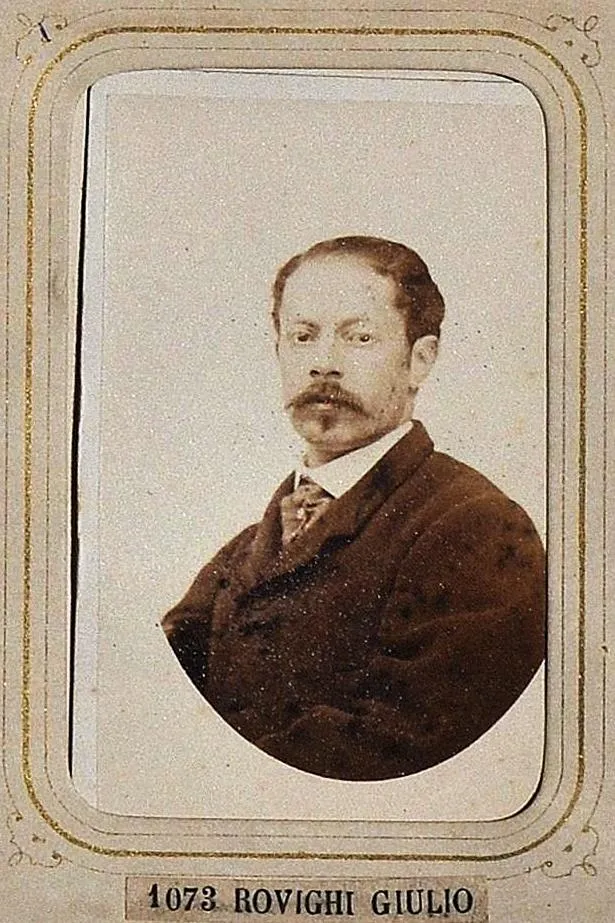

(2) GARIBALDI'S SEVEN: Giacomo Alpron, Donato Colombo, Angelo Donati, Giulio Rovighi

(1) "GOLDBERG, MEET GARIBALDI!"

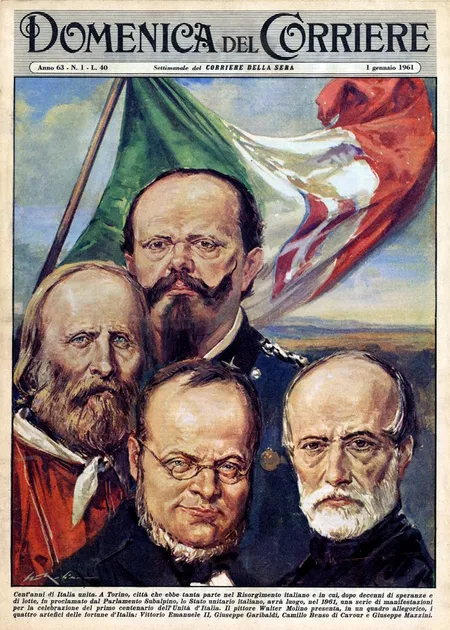

Giuseppe Garibaldi sailed from Quarto (on the outskirts of Genoa) for Sicily on May 5-6, 1860, accompanied by a band of fervent supporters dedicated to the cause of Italian Nationhood. Their immediate goal was to liberate (or annex, some would say) the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies—the southern third of the emerging geopolitical state.

The Mille di Garibaldi (Garibaldi's Thousand) landed at Marsala on May 11, 1860. Among them was my fantasy doppelganger Antonio Goldberg.

I first encountered Antonio Goldberg—evidently Hungarian, more or less Jewish it would seem—in Florence about forty years ago at the local headquarters of the Associazione Veterani e Reduci Garibaldini (Association of Garibaldi Veterans and Returnees).

The ANVRG is a place where elderly nationalists hang out, sharing a mildly companionable nationalism with little or no politics involved. The last surviving member of Garibaldi's Mille died in 1934 (Giovanni Battista Egisto Sivelli, Genoese, aged 91). While no one you meet at the ANVRG actually deployed with Garibaldi, it is often easy to imagine that they did.

I lived in the neighborhood at that time and often passed by. One afternoon, the massive bolt-studded door of their medieval tower was propped open. In the tiny piazza out front, a cluster of old guys perched on folding chairs—smiling expectantly.

"What's the occasion?", I barely had time to ask. They waved me in to a teeming display of miscellaneous memorabilia: flags of course, plus medals, cockades and spurs; hats, scarves and epaulets; letters, commendations and proclamations; a small pocket diary (punctured by a bullet hole, unless I saw that item some place else and my mind is now playing tricks).

Also, a bound copy of the Albo d'Oro (Golden Registry), listing the Mille in aphabetical order by surname. Like most people, my silly instinct was to check my own name first, notwithstanding the zero-to-none chance of finding a Goldberg in the mix.

Except...there it was...so go figure?

ANTONIO GOLDBERG (number 518 of 1089)

518. GOLDBERG Antonio. Mancano notizie ufficiali.Taluno afferma essere egli nato a Pest (Ungheria) nel 1826; tenente nei cacciatori delle Alpi nel 1859; sergente nella 6^ compagnia a Talamone. Alla presa di Palermo avrebbe riportato due ferite; appartenuto di poi al corpo invalidi, sarebbe morto nel 1862 a Sorrento (o Salerno?).

In English:

518. GOLDBERG Antonio. Official notices are lacking. It has been asserted that he was born in Pest (Hungary) in 1826; lieutenant in the Alpine Hunters 1859; sergeant in the Sixth Company at Talamone. He was reportedly wounded twice at the taking of Palermo; then he was part of the invalid corps. He reportedly died in 1862 in Sorrento (or Salerno?)

Whatever the course of the Italian Experiment, no one—in 1860 and the years after—doubted that the Mille were essential to the emerging creation story.

The smoke had barely cleared when the new regime began gathering information, documentary but also word of mouth, regarding even the lesser protagonists. An initial list of Garibaldi's cohorts was published in 1864, then a more nearly definitive one in 1878.

Goldberg's cursory CV (which I cite above) is evidently sourced from this latter list. Here is a quick run-through of those assertions, plugged into a simple time-line:

Goldberg got an early start, in the Cacciatori delle Alpi (Alpine Hunters). These were Garibaldi's early shock troops, active in the far north of Italy and instrumental in the annexation of Lombardy to the nascent Kingdom of Italy in 1859.

He then embarked with Garibaldi, setting sail from Quarto (now known as Quarto di Garibaldi) on 5-6 May 1860. They stopped in Talamone (on the Tuscan Coast) on 7 May 1860 (reportedly with Goldberg).

Goldberg, Garibaldi and the others landed at Marsala (in Northwest Sicily) on 11 May 1860 (as noted in the bio).

The Mille fought and won the Battle of Calatafimi on 15 May 1860 (presumably with Goldberg, who was with Garibaldi's troops before and after this engagement).

They moved on to Palermo and took it by siege between 27 and 30 May 1860 (Goldberg was reportedly wounded twice).

Goldberg was then evacuated to a military hospital in either Salerno or Sorrento (both near Naples), where he reportedly died in 1862, after a long convalescence.

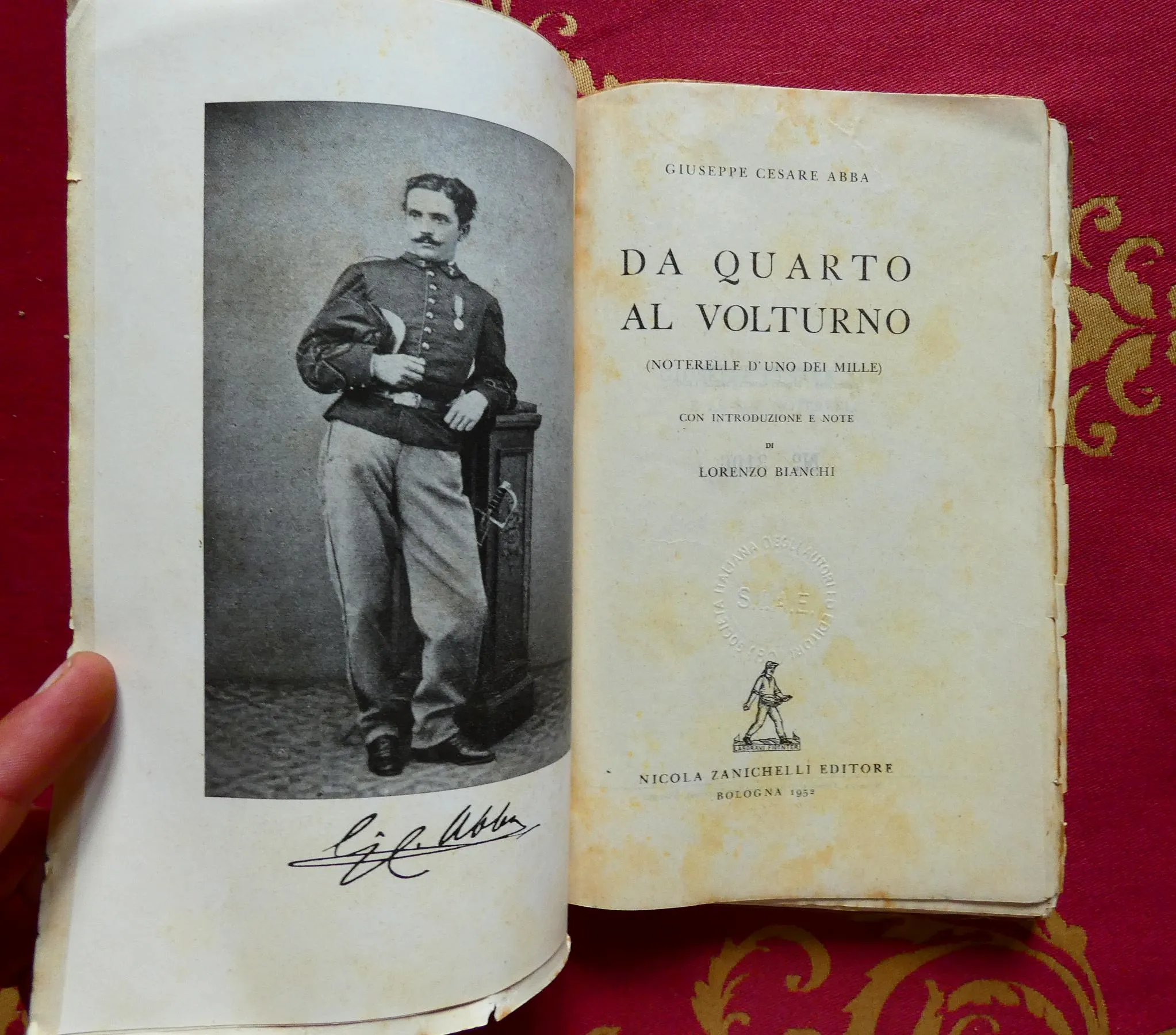

"Official Notices" aside, more than a thousand combattents accompanied Garibaldi to Sicily, while countless others looked on—soon adding their own facts and fantasies to the mix. Probably the most compelling eye-witness account of the expedition was the memoir of the then young Lieutentant Giuseppe Cesare Abba. As it happened, Abba was the immediate superior of Sergeant Goldberg.

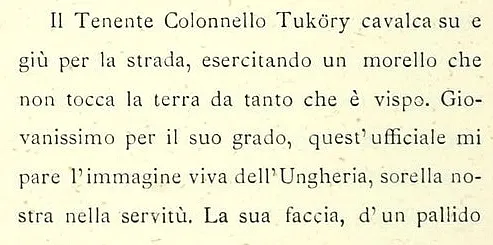

Decisively Hungarian (to Abba at least), Goldberg appears in the penumbra of the glamorous Magyar nationalist Lajos Tüköry:

"Lieutenant Colonel Tüköry displayed his horsemanship, riding his black stead up and down the street, so sprightly that they barely touched the ground. Young for his rank, this officer seemed the living image of Hungary, our sister in servitude. His face, pallid but shadowed, was finely outlined, illumined by a pair of flashing and tragic eyes...Hungary has two worthy representatives here, [Lajos] Tüköry and [István] Türr, plus two simple soldiers: that savage that I saw on board the ship [from Quarto to Marsala] and Sergeant Goldberg in my company. He was an old soldier, taciturn and moody but staunch, with a bold heart. We saw him at Calatafimi!" (pp.100-101).

Abba never mentions Sergeant Goldberg's first name (Antal, Anton or something else?) and there is no hint that he was Jewish (although other members of the Mille were evidently recognized as such). At that time, there were only four Hungarians noted in Garibaldi's expeditionary force (more would soon appear). While not of the officer class (like Tüköry and Türr), neither was Goldberg a "savage" (unlike the Magyar primitive that Abba describes elsewhere in colorful terms, p. 49).

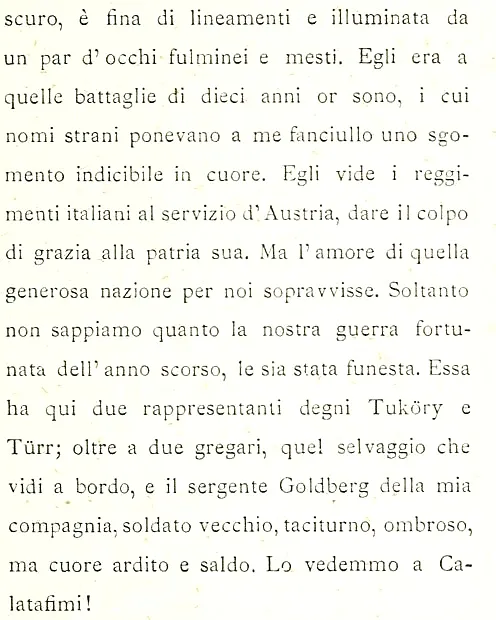

While cast as an "old soldier", Goldberg was only in his mid-thirties at that time, so "hardy veteran" is perhaps a more accurate term. In any case, neither he nor the slightly younger Tüköry had much longer to live—both fatally wounded (but not instantly killed) at the Battle of Palermo (27-30 May 1860).

"Tüköry is dead, but not in full view of the sun, not before our eyes in battle. His soul did not fly away amidst the cries of the victors but rather his life was extinguished bit by bit. He lay in bed, watching death come slowly, he who had galloped boldly into the fray clenching his sword in his fist. His leg was broken by a ball at the Ponte dell'Ammiraglio [in Palermo], but even then (it is reported), he remained on horseback to lead us. They cut off his leg and then gangrene came to kill him. Goldberg, my old Hungarian sergeant, was laid low by two wounds on [that same] morning of 27 May. When he learned of the death of his Lajos, he drew the sheet over his face and didn't say a word. Covered like that, he seemed dead himself, but perhaps he was thinking of the Magyar recruits who would be returning to Hungary without that splendid and wise cavalier, who passed through this world expending his generous spirit." (pp.174-75).

Tüköry's trajectory paralleled Goldberg's—in Abba's mind, at least—since both were Hungarian. One, however, was a glorious cavaliere and one salt-of-the-earth "other ranks". When the writer made his "seemed dead himself" observation, he was apparently not aware that the sergeant would eventually succumb to wounds incurred in Palermo on 27 May 1860.

More information regarding Goldberg is evidently available, as teased by La nascità di una Nazione: Le 1000 storie dei Mille di Garibaldi (The Birth of a Nation: The 1000 Stories of Garibaldi's Mille), a fascinating but sometimes loosely documented online resource. Goldberg is there called "Antal" by name and described as "a rough old soldier who deserted the Austrian army for love of Hungary". He was born on 2 October 1826, "probably to a Jewish family" in "Budapest" (perhaps Pest, since Budapest was not configured as a single city until 1873).

"He served for 12 years in the Imperial [Habsburg] Army and was a student in the military school in Trieste and then a sergeant. In 1859, he deserted the regiment of Baron Bianchi in which he served and on 26 May 1859 enrolled in the Second Regiment of the Cacciatori delle Alpi. He was one of four Hungarians who sailed from Quarto with the Mille...At Talamone, he was assigned to the Sixth Company of the Mille. He fought with honor at Calatafimi...On 27 May [1860] he received two wounds at the Ponte dell'Ammiraglio [in Palermo], one on the right arm and one to the trunk. As a result, he was promoted to Second Lieutenant but not subsequently redeployed, since he never fully healed. In Sorrento, he was admitted to the Casa Reale degli Invalidi [Royal Hospice for Invalids), where he died probably in 1862. He was decorated with the Silver Medal for Military Valor."

This itinerary makes good historical sense, in so far as it goes. Goldberg came to Italy by way of the Austro-Hungarian territory of Trieste, at a time when much of northern Italy was still ruled by the Habsburgs. He would have served under a virulent opponent of Italian nationalism: Feldmarschalleutenant Vinzenz Ferrerius Friedrich Freiherr von Bianchi, Herzog von Casalanza (he died in 1855, but his regiment remained).

In 1859, Lombardy was agitating for freedom from Austria and union with the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, so Goldberg faced a stark choice. Either he fought on behalf of the Italians or against them, aiding the same oppressors who subjugated his native Hungary. After the liberation of Lombardy, the obvious next step was to follow Garibaldi into the South. Then came his fatal injuries in Palermo, his transfer north with the advancing Italian forces and his eventual death near Naples.

(2) GARIBALDI'S SEVEN: Giacomo Alpron, Donato Colombo, Angelo Donati, Giulio Rovighi

It is usually said that seven Jews followed Garibaldi to Sicily in 1860. Sergeant Goldberg is not included among them—maybe because he wasn't Italian, maybe because he wasn't Jewish or maybe because he simply slipped through the cracks of history.

At that time, there were some 34 thousand Jews in the territory of the nascent Italian state, which had a cumulative population of approximately 26 million. In other words, 1 in 4,857 Jews took part in Garibaldi's mythic venture but only 1 in 26,000 Christians.

This is an impressive showing, but probably more anecdotal than statistical. Meanwhile, the alleged documentation is often tenuous and unsourced, especially as cited in online treatments.

Then we have the age-old issue: What is a Jew? A race...an ethnicity...a religious creed...a state of mind...or all of the above at once? It is difficult enough to answer that question today, without looking back across the centuries.

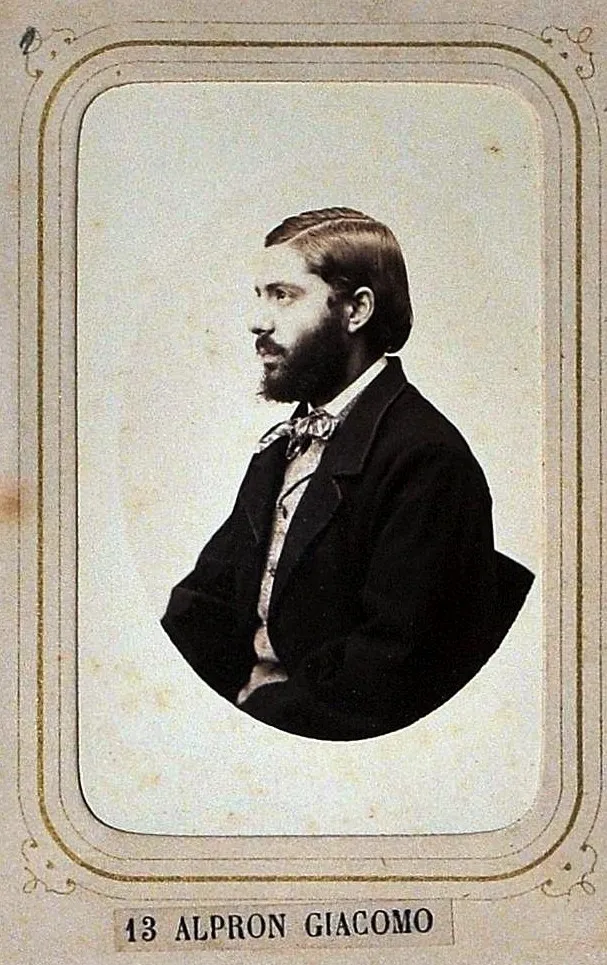

Who were Garibaldi's Seven? In alphabetical order: Abramo Isacco Alpron, Donato Colombo, Angelo Donati, Francesco Grandi, Riccardo Luzzatto, Eugenio Ravà and Giulio Rovighi.

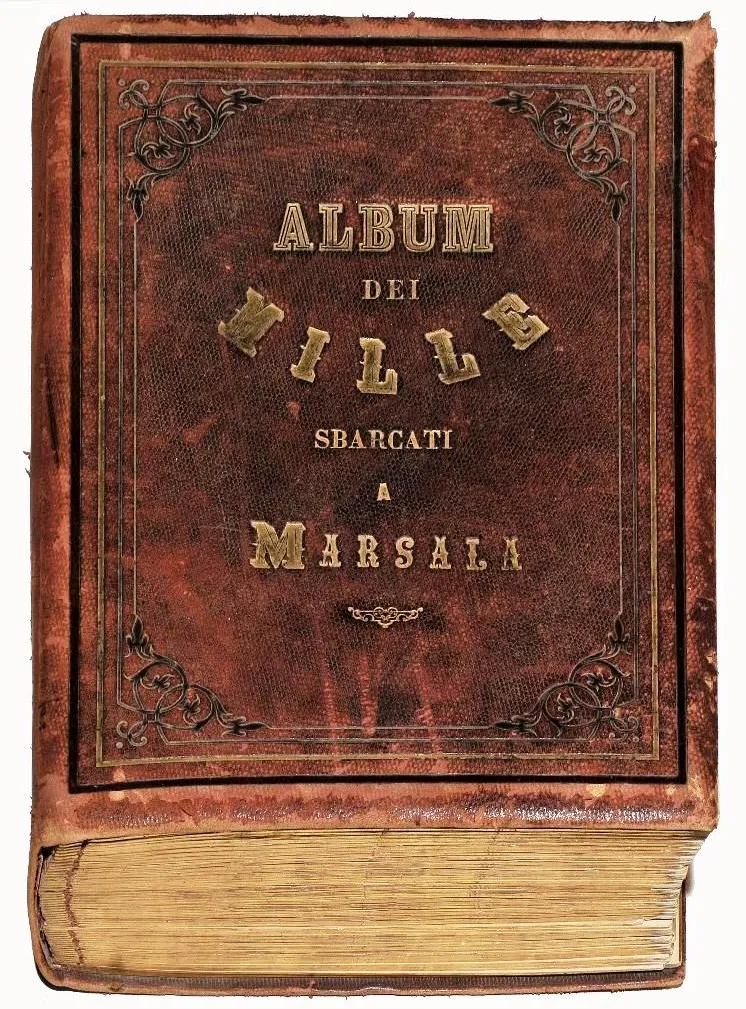

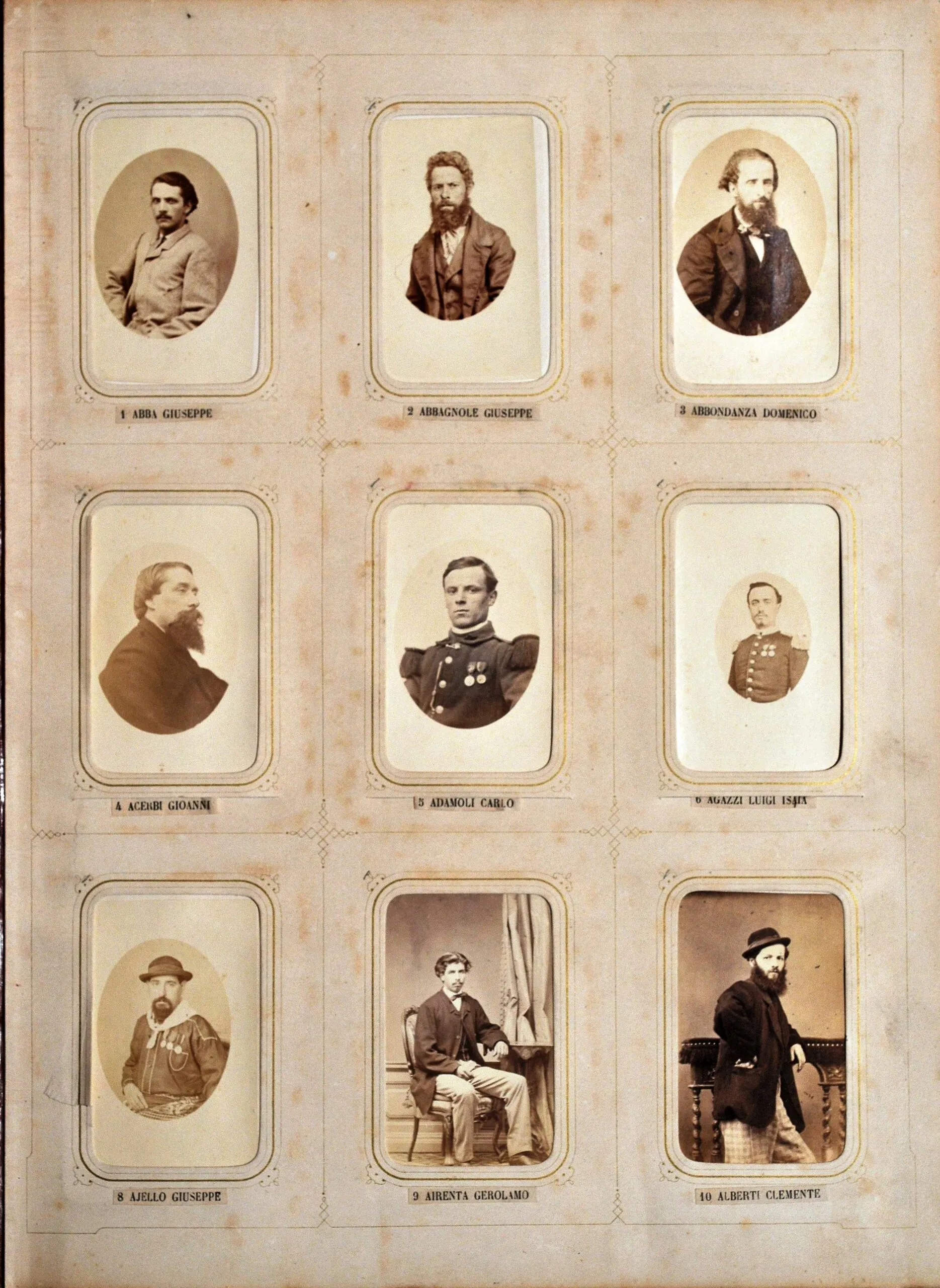

We have photographs of all seven of them—amazing to say.

We owe these compelling human documents to Alessandro Pavia, an enterprising Milanese photographer. Over the course of five years (1862-67), he compiled as many likenesses as he could of the 1092 known Mille. Some were copies of extant photos while others were shot in his studio in Milan, only recently wrested from Austrian control.

Pavia succeeded in collecting 824—an impressive figure considering the number of dead and lost, not to mention the vagaries of transportation and communication in a still-unifying Italy. (Austria ruled the territory of Venice until 1866. Rome, the destined capital, was not secured until 1870. Trieste and the Trentino remained in Austrian hands until 1920.)

"Giacomo" was the Italian name of the unequivocally Jewish Abramo Isacco Alpron, from a family of businessmen in Padua (a city on the Venetian mainland with an old and substantial Israelite community). Padua was ruled by the Austrians at the time of his birth and he evidently joined the Cacciatori delle Alpi (Alpine Hunters) in the Lombard Campaign of 1859 (where he might have encountered Antonio Goldberg).

According to a colorful and quite likely true story, he secretly sold family furniture in 1860, to finance his journey to Genoa to join Garibaldi's Mille. Alpron fought at Calatafimi (alongside Goldberg). In 1867, he took part in Garibaldi's inconclusive first assault on Rome. After these adventures, Alpron returned to the fold—resettling in Padua, marrying and immersing himself in the family business. In 1900, he died in his boyhood home and was buried in one of the city's Jewish cemeteries.

Donato Colombo was born to Abramo Colombo and Grazia Levi in Ceva di Mondovì , a small town in southwestern Piedmont ruled by the generally liberal and progressive House of Savoy, soon to become the Kings of United Italy. Jews in that state were granted full civil rights in 1848, when Donato was ten years old and in 1857 he enrolled in the Faculty of Mathematics at the University of Turin.

In 1860, he joined Garibaldi at Quarto and embarked for SIcily, taking part in major engagements from Calatafimi, to Palermo (where he was promoted from sergeant to second lieutenant) to Volturno (where he was wounded) and Naples (where he convalesced). His patriotic feats constitute an early chapter in a long and tranquil academic career. He taught mathematics in various schools in Trapani (Sicily), then moved to Milan in 1878 where he eventually became principal of an old and prestigious high school, the Liceo Cesare Beccaria.

Angelo Irach Donati, son of Giacomo Donati and Annetta Luzzatto, was born in Padua on the Venetian mainland (as was Giacomo Alpron). Like many Jews, he was an outspoken Italian monarchist from an early age.

In the days of Austrian rule, that was a relatively liberal and progressive position, diverging however from Garibaldi's revolutionary socialism. Donati joined the Mille and was wounded in Palermo (like Goldberg and Colombo). After returning home, home, he spent the rest of his life in business in Padua and Milan.

For the Record: Angelo Irach Donati is not to be conflated with another slightly younger Angelo Donati (1847-1897) from a substantial Jewish family in Modena. He distinguished himself in the Trentino during the Third War of Independence (1866), then made a sucessful career in Milan with the Donati-Jarach Bank, a notable Jewish operation in those years.

Giulio Rovighi was born into a family of Jewish wine merchants in Carpi, then part of the Dukedom of Modena and Reggio. In 1848, he joined other local volunteers in the first War of Independence against the Austrians in the North. After the armistice, he settled in Turin until the next insurrection in 1859 (the Second War of Independence, against the Austrians once more but in concert with the French). Rovighi then segued into Garibaldi's 1860 sweep into the South, following him to Sicily, then up through the mainland, first as Second Lieutenant then Major. After the declaration of the Kingdom of Italy in March 1861, he resigned his commission and was awarded a Silver Medal for Military Valor.

The police in Turin then put a kink in Rovighi's patriotic aspirations, discovering that he had formerly managed a brothel in that city. While not quite illegal, such activity was morally unbecoming for an alleged hero, so he lost his military pension and was banned from displaying his medal.

When the Third War of Independence broke in 1866 (with the French, against the Austrians), he was allowed to enlist but only as a private soldier. Soon, however, he won back his commission and another silver medal, then in 1867 joined the largely unsuccessful Italian incursion into Roman territory (The Italian nationalists was now fighting both Pius IX and Napoleon III of France.)

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.