GARIBALDI & GOLDBERG LAND IN SICILY: A Jewish View of the Italian Risorgimento (Part 2)

CONTENTS:

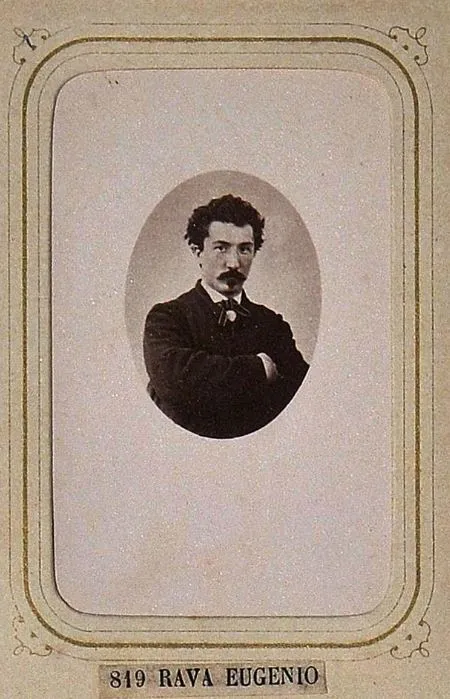

(3) GARIBALDI'S SEVEN: Eugenio Ravà

(4 ) GARIBALDI'S SEVEN: Riccardo Luzzatto (and family)

(5) GARIBALDI'S SEVEN: Francesco Grandi (and Luigi Grandi/Tobia Ariento)

(3) GARIBALDI'S SEVEN: Eugenio Ravà

In the case of Eugenio Ghion Aron Ravà, we can begin with the memorial stone that the city of Parma placed on his tomb in the Jewish Cemetery there. The municipal officials could hardly do less, since he was a long-standing member of the town council. When it came to the text, there was no more eloquent testimony than a commendation penned by Giuseppe Garibaldi himself.

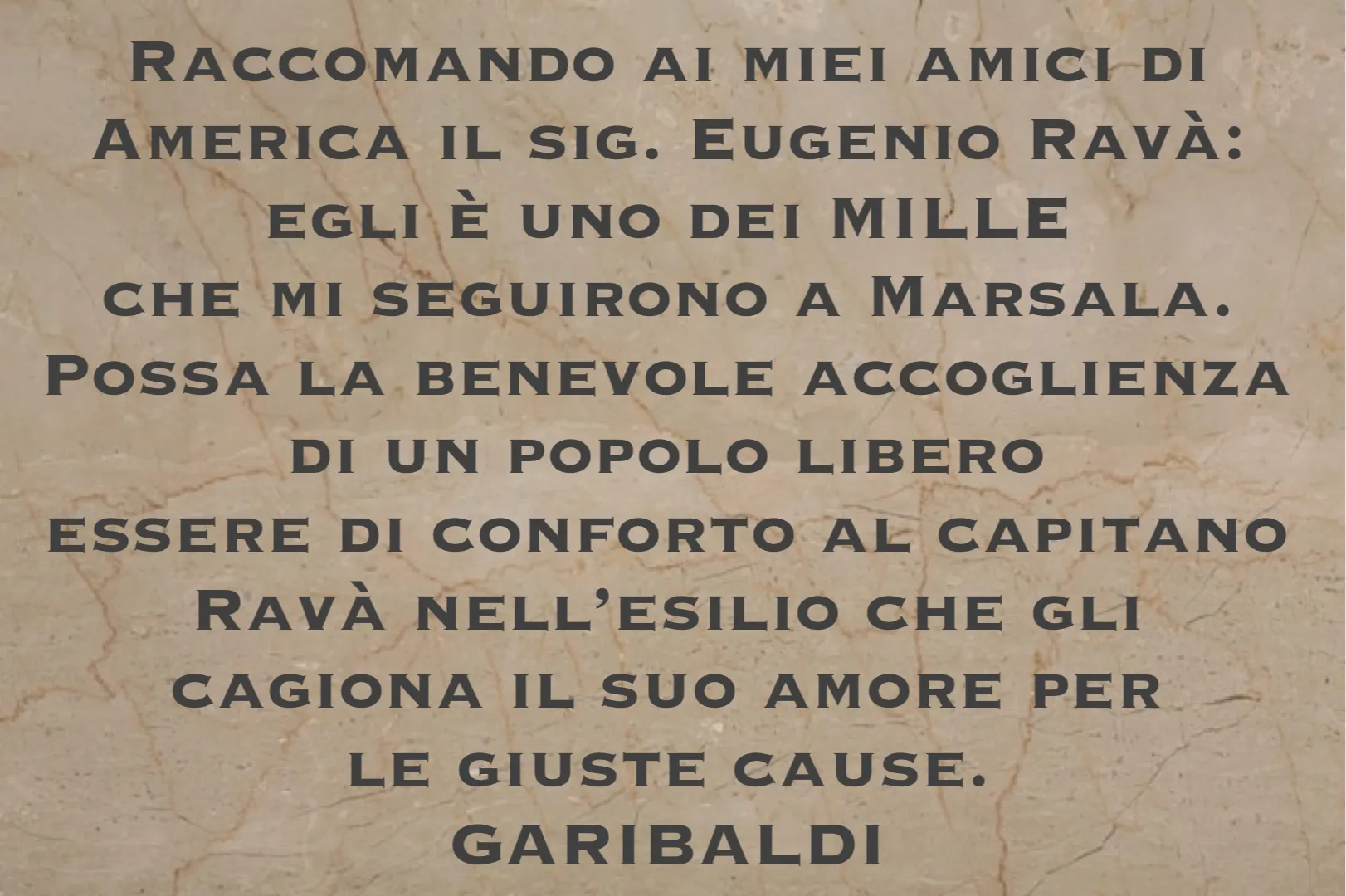

"To my friends in America, I commend Mr. Eugenio Ravà. He is one of the THOUSAND who followed me to Marsala. May the benevolent welcome of a free people comfort Captain Ravà in the exile occasioned by his love of just causes. GARIBALDI"

Eugenio (Ghion was his Jewish name) was born to Leone Ravà and Allegra Liuzzi, business people in Reggio Emilia in the Dukedom of Modena (not far from Rovighi's Carpi). He was studying in Parma in 1859, when he and his two brothers Enrico and Federico took off for Lombardy to fight the Austrians. After that campaign, he joined the regular Piedmontese military as a Bersagliere (Sharpshooter) and was stationed at Porto Santo Stefano on the coast of recently annexed Tuscany. When Garibaldi and his Mille landed at nearby Talamone on their way to Marsala, Ravà stowed away on one of their two ships—effectively deserting the royal service. During the Southern Campaign, he advanced from Second Lieutenant to Captain in the nationalist army, mustering out in the spring of 1861.

That age of revolution was strewn with disjointed lives, especially of young men who tumbled into the fray—then couldn't get out again. When Ravà reappeared in Parma in 1861, it had been recently absorbed into the new Kingdom of Italy. However heroic his exploits on the Garibaldi front, the Royal Army still viewed him as a runaway Bersagliere.

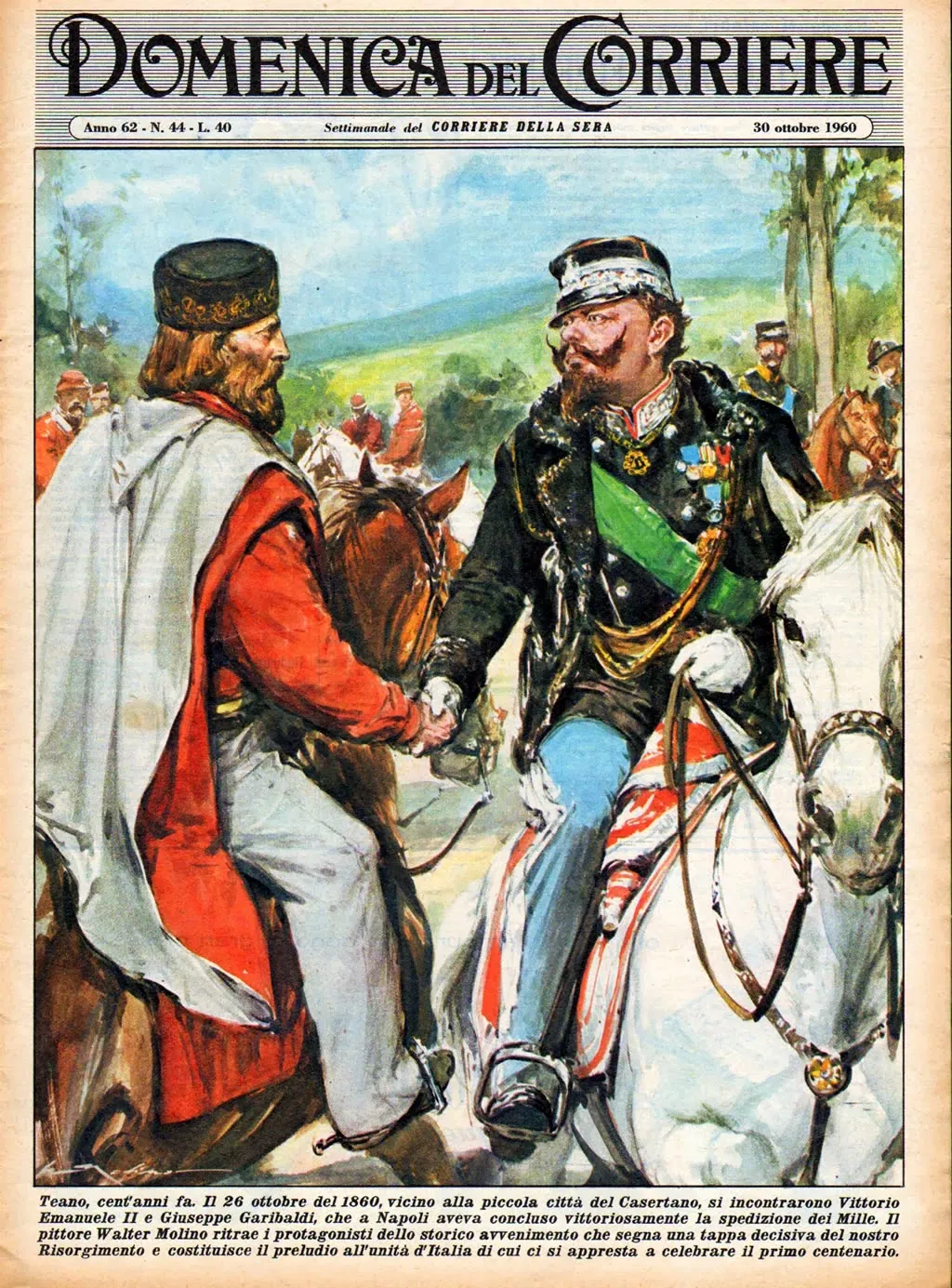

"Teano, a hundred years ago. On 26 October 1860, near a small town in the area of Caserta, Vittorio Emanuele II met Giuseppe Garibaldi, who had concluded the Expedition of the Mille in Naples. The painter Water Molino portrays the two protagonists of this historic event which marked a decisive phase in our Risorgimento. It offered a prelude to the Unity of Italy, the centennial of which we will soon be celebrating." The illustrator does not disguise their essential dislike and distrust, which sometimes erupted into open hostility.

Ravà was promptly arrested in Parma and sentenced to a year in prison, but the military authorities were loathe to waste a good fighting man. They commuted their decree on condition that he reenlist in the Bersaglieri—which he did with the rank of sergeant. Within a year, however, he deserted yet again, following Garibaldi into the mountains of Calabria.

Giuseppe Garibaldi was a radical republican in the service of an ambitious monarch. A man of principle, he believed deeply in "Italy" while only tolerating "The Kingdom of Italy" as a strategic necessity. By the time of the Aspromonte campaign, there seemed to be no lines that Vittorio Emanuele II would not cross. In 1860, he ceded the city of Nizza / Nice—Garibaldi's beloved home town—to Napoleon III in return for his support against the Austrians. After a bogus referendum, the French emperor immediately scrubbed every trace of its Italian identity, precipitating a mass flight across the new border. Then there was the looming issue of Rome, Italy's natural capital. Napoleon III staunchly defended the Pope's territorial rights and Vittorio Emanuele II seemed inclined to let him have his way.

At Aspromonte, there was an armed struggle between the Nationalists and Royalists. Wounded then arrested, Garibaldi would soon be exiled (for the first of various times) to an isolated island off the coast of Sardinia.

Eugenio Ravà could not return to the Bersaglieri after his second defection. With Garibaldi's letter of recommendation in hand, he disguised himself as a peasant and made his way to Liverpool. There he embarked for America, then in the grip of a civil war.

"Giuseppe Garilbaldi, Hero of the Two Worlds, lived here as an exile from 1851 to 1853". This Italian commemorative plaque was "placed by a few friends" on 8 March 1884 at the Garibaldi-Meucci House on Staten Island.

The infinitely charismatic Garibaldi was a celebrated figure there. He had lived on Staten Island for two years, while waiting out an anxious pause between revolutions. In 1862, President Lincoln offered him a commission as Major General in the Union Army but he was more than fully engaged with his own campaigns. In 1863, he sent Lincoln a letter of congratulation on the newly-issued Emancipation Proclamation.

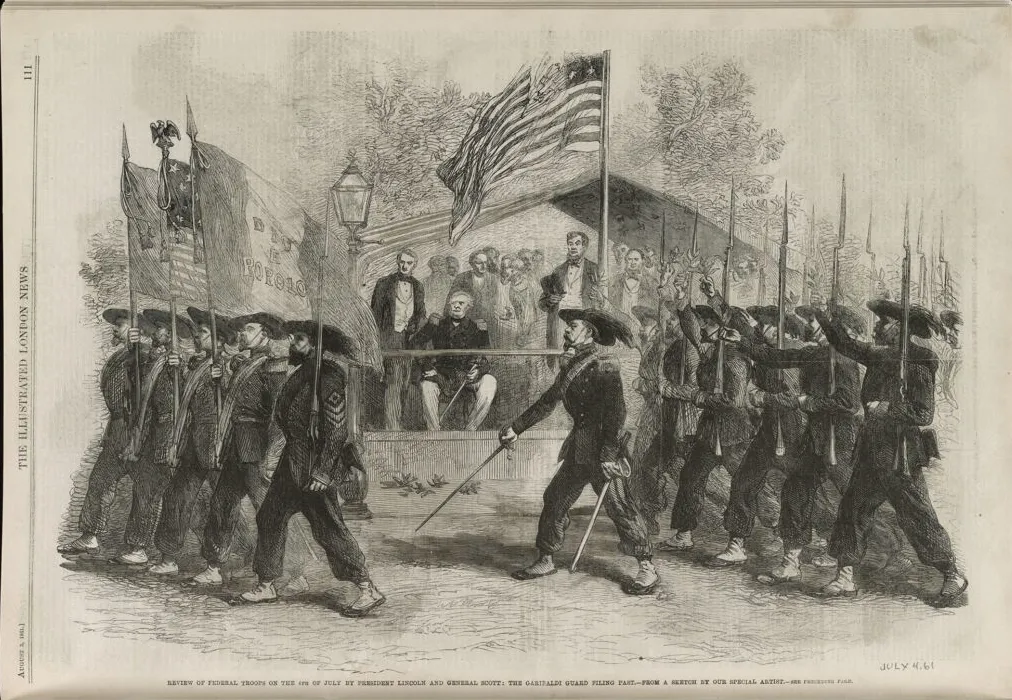

The 39th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment—better known as "The Garibaldi Guard"—was the most conspicuous embodiment of his spirit. Active from 1861 until 1865 (but often reorganized), it initially consisted of ten companies divided along geographical and linguistic lines: three German, three Hungarian, one Spanish and Portuguese, one Swiss, one French and one Italian. Although Italians were only a minority (one in ten) in this particular regiment, there were many others in the Union Army, often in predominantly foreign detachments, sometimes recruited in Europe. Italians with anti-Garibaldi and anti-Unification sympathies tended to gravitate to the Confederates. (For the case of Nunzio Finelli of Naples and Philadelphia, a staunch Union Man, see Whose Columbus? Whose Columbus Day?)

Ravà presented Garibaldi's letter to the Union military command—where and when we don't know. He then fought under Ulysses S. Grant for the duration of the conflict, with his old rank of Captain. The General certainly knew that this latest foreign volunteer was Italian but did he also know that he was Jewish? And did Grant actually try to ban Jews from the Union Army, as was widely believed?

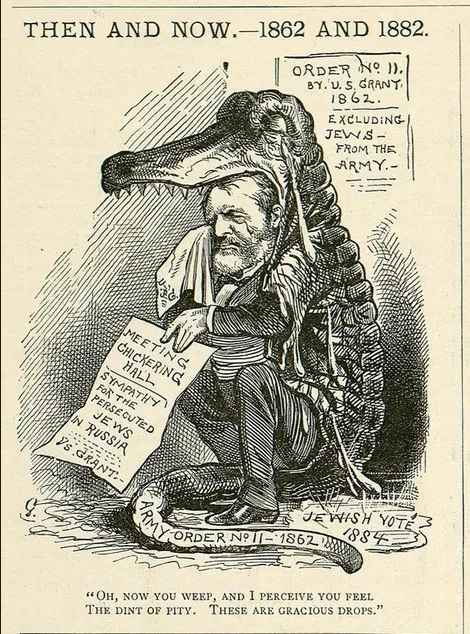

On December 17, 1862, Ulysses S. Grant issued General Order No. 11, with the categorical pronouncement “The Jews, as a class, violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department, and also Department orders, are hereby expelled from the Department.”

The story was a complicated one, involving the provision of cotton for Union uniforms and the blockade of Southern ports. A clique of Jewish merchants from Cincinnati (in the General's home state of Ohio) was playing fast and loose with the regulations, conniving with his own father Jesse Grant. In any case, there were many Jews in the Union Army (and some in the Confederate Army too). The "Department of the Treasury" was explicitly indicated in the order, not the "War Department" (as it was then known).

Grant regretted the wording almost immediately, especially the reference to "Jews as a class", then spent the rest of his politcal life back-tracking, seldom coherently. While running for president in 1868, he issued a widely published letter of apology to Jewish Congressman Isaac Morris. “I do not pretend to sustain the order...the order was made and sent out, without any reflection, and without thinking of the Jews as a sect or race to themselves, but simply as persons who had successfully violated an order...I have no prejudice against sect or race, but want each individual to be judged by his own merit. General Orders No. 11 does not sustain this statement, I admit, but then I do not sustain that order.”

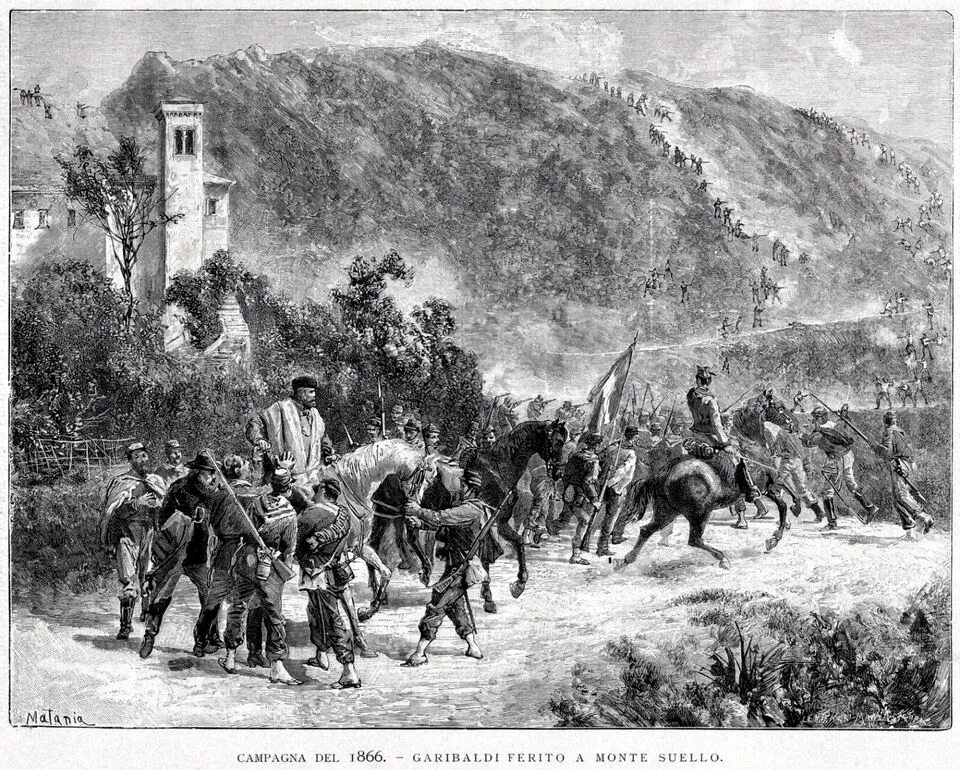

When Ravà returned to Italy in 1865, he was a deserter (yet again) from the Royal Army. Promptly arrested and sentenced to another year in military prison, he was soon released. At the outbreak of the Third War of Independence in 1866, he rejoined Garibaldi in the far north, fighting at Lodrone and Monte Suello.

In 1867, Ravà moved south with Garibaldi in his latest attempt to take Rome. The Italians were then slammed by the massed forces of Pope Pius IX and Emperor Napoleon III, dimming their dream of Roma Capitale—for the time being at least.

For once, history moved at lightning speed... In 1870, the Prussians invaded France and Napoleon III recalled his troops from Rome, leaving Pius IX to his fate. The Army of Vittorio Emanuele II then stormed the Eternal City and the Unification of Italy was essentially complete.

The taking of Rome was a Royal not a Red-Shirted affair. Garibaldi and Eugenio Ravà were otherwise engaged, harassing the Prussians in Northeastern France on behalf of the newly declared Third French Republic.

After ten years of chasing nationalist revolutions (or having nationalist revolutions chase him), Ravà ran out of wars to fight. He was still relatively young, with a life to live, so he resettled in Parma in 1878. There he worked as a commercial agent and involved himself in local affairs.

The drama of his early years was known to all and evidently admired—along with his progressive ideals and his religious heritage—recorded in that simple yet compelling inscription in the local Jewish cemetery.

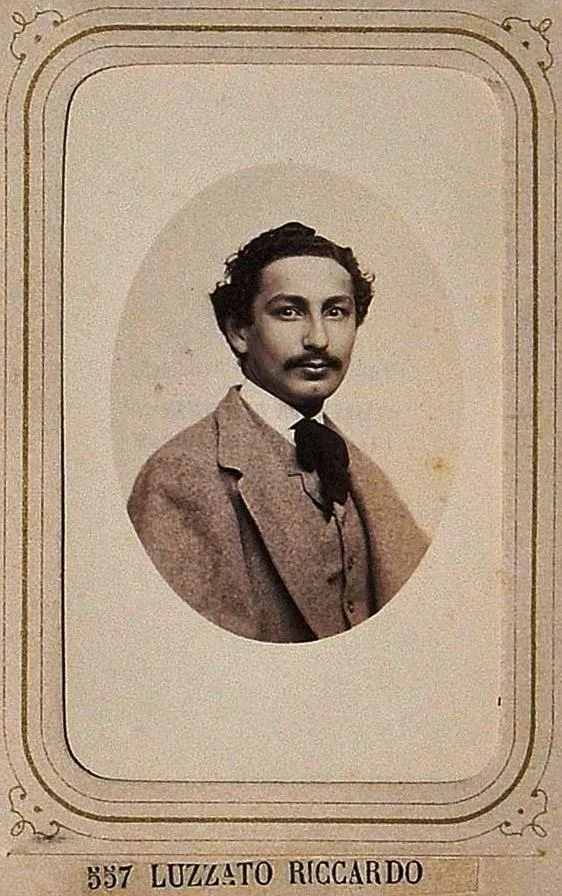

(4) GARIBALDI'S SEVEN: Riccardo Luzzatto (and family)

Riccardo Luzzatto would have been extraordinary in any family but his own. His father Mario Luzzatto (1796-1876) married his mother Fanny (1817-92, daughter of Abramo and Anna Senigaglia), then settled in Udine, the chief city of the Friuli—a linguistically and culturally diverse region between the Venetian mainland and present-day Slovenia. Mario developed his family's interest in the local silk trade and consolidated their fortune. Meanwhile, he and his wife threw themselves into the joint cause of Italian and Jewish self-determination, beginning with the anti-Austrian insurrection of 1848.

Mario had a position in the provincial government and refused to ratify Udine's surrender to Count Laval Nugent von Westmeath (an Austrian general of Irish birth), resulting in his imprisonment in distant Moravia. While a decisive figure in his own right, it was his wife Fanny and his daughter Adele who captured the imagination of Italian patriots in the Friuli and beyond.

The Luzzatto women were in close touch with other protagonists of Italian Unification, including Giuseppe Garibaldi and Giuseppe Mazzini. They provided material support to the cause along with moral inspiration.

In 1860, when 18 year-old Riccardo Luzzatto absconded from the family home to join Garibaldi's Mille, his mother followed closely behind, arriving in Quarto with her son-in-law Graziadio. While expressing her maternal solicitude directly to the leader of the expedition, she also made a significant financial contribution.

The Luzzatto were active in politics, industry, journalism and the law, playing an immense role in a unifying and then unified Italy. Riccardo reinforced his commitment to their family identity by marrying a somewhat distant Viennese cousin Emilia Luzzatto (she was an eminent writer and translator, with the pen name of Emilia Nevers).

However monumental the Luzzatto dynasty, they were not always fighting on exactly the same side.

Garibaldi had never been convinced by the whole Kingdom of Italy thing and there was an armed conflict between Royal and Nationalist forces at Aspromonte, in the wilds of Calabria, on 29 August 1862. Riccardo Luzzatto (like Eugenio Ravà) remained faithful to the insurgents while his brother Adolfo Luzzatto deployed with the King's army. In that encounter, Garibaldi was wounded and taken prisoner, then pushed offstage until Vittorio Emanuele needed him again.

In 1867, Riccardo Luzzatto founded a now old and distinguished law firm in Milan, currently under the direction of another Riccardo Luzzatto, with branch offices in Israel. He sat in the Chamber of Deputies in Rome from 1892 to 1913, often legislating alongside his brothers Attilio and Arturo. Riccardo remained fervently anticlerical and a committed Freemason, but began expressing monarchist sympathies late in life. On 23 March 1919, he attended the founding conference in Milan of the Fasci italiani di combattimento which would emerge as Mussolini's Fascist Party two years later. The Fasci italiani began as an interventionist organization, opposed to Italian neutrality during the First World War—so proto-Fascism was an impeccably patriotic choice (even for Jews, who could hardly guess what history held in store).

(5) GARIBALDI'S SEVEN: Francesco Grandi (and Luigi Grandi/Tobia Arienti)

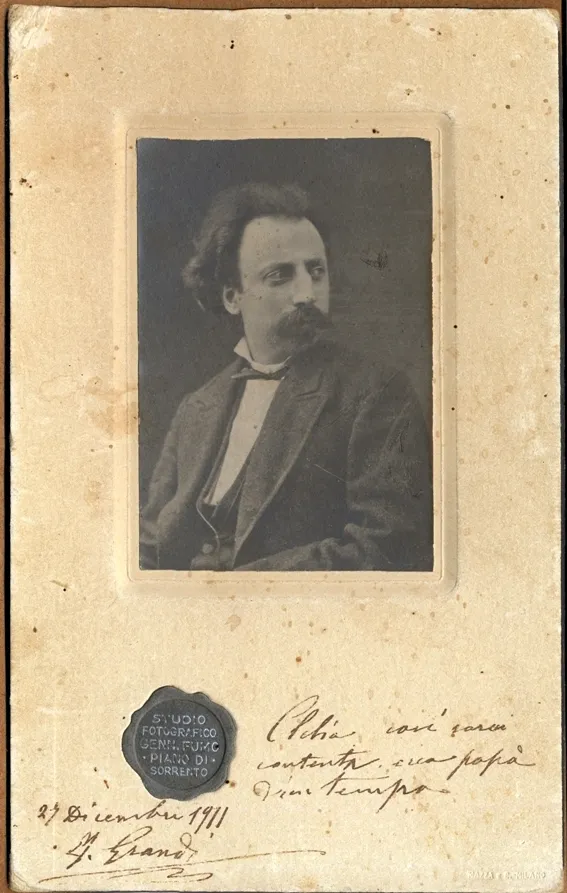

The Grandi Succession—Luigi then Francesco—occupies a special place in the annals of both Italian patriotism and Israelite shape-shifting. While there are gaps in the story, which is largely pieced together from Francesco’s own swashbuckling memoir, enough remains for one hell of a family saga.

Francesco's father Tobia Arienti (1805-1857) was born in Lissone in the Lombard hinterland (near Monza) to Ignazio Arienti and Teodolinda Formentoni. According to Francesco, Ignazio had a brother Mosé Arienti (an architectural designer), father of Carlo Arienti (1801-1873), a well-known academic painter and teacher. (Elsewhere, however, Carlo Arienti's father is identified as Gaetano Arienti, supervisor of the Botanical Garden in Mantova.)Tobia had two brothers: Abramo Arienti (an architect in Milan) and Eliseo (who moved to Rome with the temporary alias of Giovanni delle Palme), also a sister named Rebecca.

Tobia lost his Jewish-sounding appellation and presumed Jewish antecedents with remarkable speed and efficiency, since the Arienti family was both artistically and radically inclined. From an early age, he was targeted by the Austrian police as a seditious rabble-rouser, subject to immediate arrest. When his Ligurian friend Luigi Grandi was killed by gunfire in a street confrontation, Tobia appropriated his identity papers and fled—passing as "Luigi Grandi" for the rest of his life.

The new Luigi Grandi consolidated his backstory by moving to Liguria, which was then ruled by the House of Savoy—Kings of Piedmont-Sardinia and eventually Kings of United Italy. In 1830, he married Giovanna Palma in Lavagna (on the coast south of Genoa). The marriage was evidently Catholic, as was his wife, but with some room for doubt. Giovanna Palma was closely related to the Ravenna—a grand formerly Jewish family, with long histories in both Lavagna and Cagliari in Sardinia. (There is a curious article, evidently from the Fascist period, that protests far too loudly that these Ravenna were impeccably "Catholic and Aryan", distancing them from all the Jews of that name.)

Luigi's political activism made him no more popular in Liguria than it had in his native Lombardy, so he effected a strategic withdrawal to Sardinia, where he eventually settled in Tempio Pausania and made a living building houses, bridges and mills. His second child and only son was born there, named Francesco and promptly baptized in the local cathedral.

Luigi then rediscovered his natural vocation as a revolutionary, leaving his wife and family in Cagliari with her Ravenna kin. Following in the footsteps of Giuseppe Garibaldi, he crossed the Atlantic to Rio do Sul in Brazil, joining the anti-Brazilian independence movement in that heavily Italian region. In the early 1840s, Grandi and Garibaldi moved on to Uruguay, where they joined the relatively liberal "Colorado" faction in the ongoing civil war. Then in 1848, the surging force of Italian Unification beckoned them back home.

Garibaldi's brigantine "La Speranza" (The Hope) landed in his home-town of Nice, with a host of other seasoned campaigners—Grandi included. They went from conflict to conflict (fierce, but often inconclusive) in Lombardy, Lazio and then Tuscany. When Francesco Grandi finally reappeared in Genoa in 1849, he discovered that his wife was dying of malaria in Cagliari and had arranged to send him the eight year-old son he never knew.

Luigi had a family to support, so he opened a furniture factory in Genoa, where Francesco learned woodworking while absorbing his father's political creed. The boy then went off to Florence and Rome to study art, on the recommendation of his uncle Carlo Arienti, a well-known academic painter. After Luigi's death in 1857, Francesco returned to Genoa and entered the Academy there—until it came time for him to join the nationalist struggle.

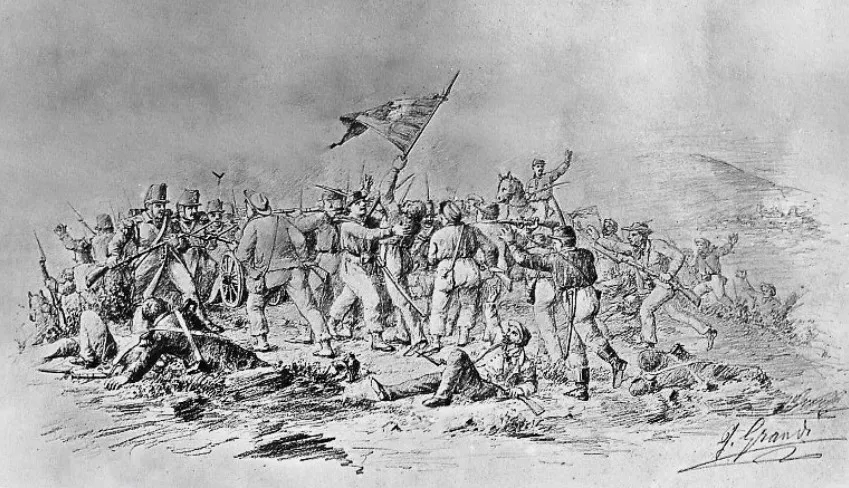

Francesco took his pencil and paper with him, when he followed Garibaldi into the Alps in 1859 and then on to Sicily in 1860. The General admired his artistic skill and—by Grandi's own account—asked him to design uniforms for the Mille.

"I showed him the sketches and he liked them, making only one comment. I had designed a close-fitting jacket for the soldiers and he wanted me to get rid of it. ‘Something of that sort would get in their way when they are marching and fighting. For the soldiers, it is better that they tuck this garment into their trousers.’ For the officers, I left the tunic as I had designed it…These are the uniforms that were then adopted.”

Francesco inherited the concept from the Uruguayan campaign, where Garibaldi's men (including his father Luigi Grandi) had already worn red shirts (not jackets). Butchers in Buenos Aires were distinguished by their loose camisas rojas/camicie rosse and the General had a rare knack for compelling imagery of this sort.

After his Garibaldi campaigns in the North and then the South, Francesco Grandi went on to live a long and full life in the new Italy. In 1861, he resettled in Cagliari, his childhood home, teaching art and developing his unique talent for furniture-making. In 1885, the authorities in Rome invited him to launch a new Regia Scuola d’Arte (Royal School of Art) in Sorrento (near Naples), specializing in wood carving and inlay. He directed this renowned institution for 28 years, until 1914.

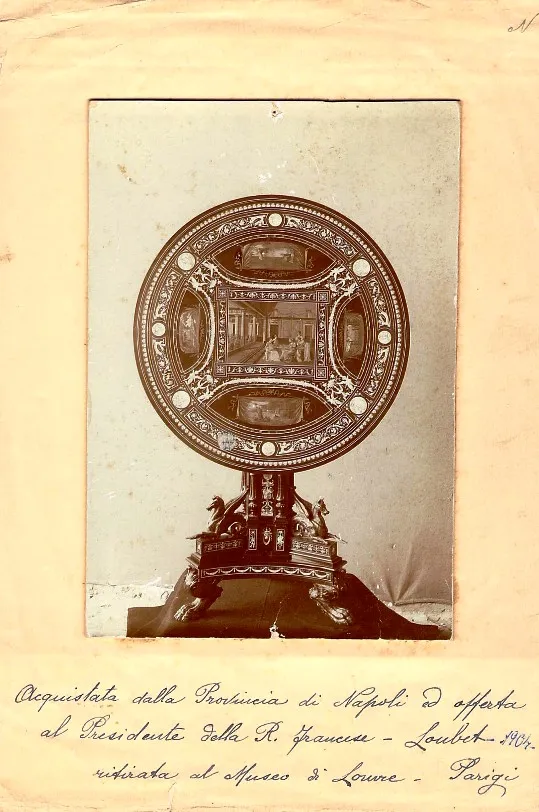

Grandi's artistic activity was proudly patriotic, exemplifying in his day what it meant to be both modern and Italian. He represented his country in World’s Fairs and other expositions, while crafting grand state gifts—like his table for the French president, Émile Loubet.

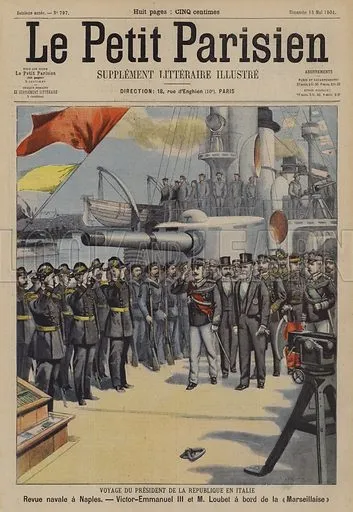

Loubet sailed into Naples in the spring of 1904. After an official welcome by King Vittorio Emanuele III, he visited that city and was presumably presented with Grandi's table. Both a skilled politician and a Radical Socialist, Loubet is best known for his entrenched opposition to the Catholic faction in France and his 1899 pardon of the falsely accused Jewish "traitor" Alfred Dreyfus. After Naples, Loubet continued on to Rome, where his anti-clerical presence infuriated Pope Pius X, contributing to a decisive break between the Church and the French Republic the very next year.

As the years passed, Francesco Grandi emerged as the most vivid and almost-last voice of the Garibaldi Expedition. On 20 April 1918, after retiring from his school in Sorrento and moving to Rome, he signed off on a highly personal and thoroughly engaging memoir, Ricordi di un Luogotenente dei Mille (Memories of a Lieutenant of the Mille). This was specifically addressed to his offspring in a less idealistic age:

To you, my dear children, I leave these brief biographical notes as a testimony, detailing my father’s adventurous wanderings and my own formation in that revolutionary environment.

I decided to interest myself no further in such matters, since they are things of the past and we have now been left behind by history and an ungrateful fatherland.

On occasion, I shared some slight notes with acquaintances who asked for my memories, but my duty is to pass them on to you in a more detailed form, since you appreciate such things and will—I feel—safeguard them zealously.

You find them here, contained in these few pages. When you read them some day, it will be as if you are hearing me once again.

In those times in which I lived, enthusiasm for Italy and for freedom was the reason for being. I adhered to the very word of my paternal faith and my father was inspired by the ideas of Mazzini. So, before telling you about me, you need to hear about my father.

It is often difficult for old men to witness the depreciation of their youthful ideals. Francesco Grandi took his old-style patriotism very seriously, so we can only wonder what was going through his mind on 6 May 1915—when he gathered with 40 other former Mille, near their point of embarkation 55 years before.

_-_Gabriele_D%27Annunzio_sdraiato_mentre_legge.webp)

Their host was Gabriele d'Annunzio, possibly a genius (as many claimed) but also an opportunist and poseur, with few values that lasted longer than he could hold his breath. His sexual exploits were mythic, his artistic experiments varied and extreme (ranging from historical romance to decadentism to futurism and back). As a political adventurist, he veered from the anarchist left to the fascist right—but with a constant swell of flamboyant nationalism.

D'Annunzio was a master of staged moments and this photo-op—with the Vate in the middle—was only one among many at that time and place.

On the previous day, D'Annunzio had delivered a chest-thumping speech at nearby Quarto, inaugurating a massive bronze monument to Garibaldi (heroically nude). Various elderly members of the Garibaldi family took part, with a parade of 20,000 patriots in the center of Genoa.

D'Annunzio was exalting a mythic moment in Italian history, while mobilizing support for his nation's intervention in the recently declared World War. But that was only part of the Quarto-Lido d'Albaro story.

D'Annunzio was a serial bankrupt, often fleeing his creditors and cooking up schemes. In 1908, the picturesquely-named Giuseppe Garibaldi Coltelletti (a purported godson of the Hero of the Two Worlds) threw himself into the development of a massive new beach resort barely two miles from Quarto. D'Annunzio soon popped into the picture, becoming a fixture of the place and generating lucrative publicity as only he could.

"Group of Survivors of the Mille/ at Lido d'Albaro / Honored by GABRIELE D'ANNUNZIO / 6 May 1915"

Who crossed out the word "onorati" (honored) in that sententious rubric? They can't have been alone in wondering who was doing the honoring—amidst whatever else.

In the group photo, D'Annunzio gave Francesco Grandi (n.23) pride of place as a ranking dignitary, at his right hand (upper left corner).

Donato Colombo (n.30, upper right corner) was present but less centrally placed—the only other Jew in the group, if we flip a coin and count Francesco Grandi.

Seated at the far left, we see Giovanni Battista Egisto Sivelli (n.11), who died at the age of 90 on November 1, 1934—winning the actuarial race as Last of the Mille.

Francesco Grandi lived longer but came in second—dropping out on June 8, 1934, at the age of 93.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.