GARIBALDI & GOLDBERG LAND IN SICILY: A Jewish View of the Italian Risorgimento (Part 3)

CONTENTS:

(6) THE JEWISH QUESTION

(7) THE JEWISH QUESTION vs. THE ROMAN QUESTION

(8) MORTARA BEGINS

(6) THE JEWISH QUESTION

"HYMN OF THE PIEDMONTESE ISRAELITES TO THEIR EXCELLENT MONARCH, KING CARLO ALBERTO: Hallelujah! Brothers, let us sing! / Hallelujah! Let all lips form this reply!/ The happy dawn of fruitful glory/ breaks over the realm of Piedmont".

These high-flown verses were published in the town of Saluzzo in 1847, composed by Marco Tedeschi (1817-69; Mordekhai ben Pinḥas Ashkenazi, in Hebrew), a young rabbi from a distinguished Piedmontese family. He was already known for his oratorical powers and musical skills, as well as his mastery of both Talmud and classical literature.

Tedeschi's hymn was hopeful, heralding a Jewish emancipation that was yet to come. Like their brethren throughout Europe, the Jews of that realm were caught in an age-old dance with steps forward and steps back.

In 1800, the Jews of Catholic Piedmont were granted full social, political and economic rights, along with Waldensian Protestants. Then in 1824, they were disenfranchised and shoved back into their old Ghetto, most conspicuously in the Savoy capital of Turin.

What mattered most to the ruling house (Dukes of Savoy, later Kings of Piedmont-Sardinia, then Kings of Italy), was their emerging place on the political map of Europe. In the long race to dominate an eventual United Italy, they advanced steadily to the head of the pack while other contenders dropped out.

While branding themselves as enlightened rulers of a liberal state, Carlo Alberto (1798-1849) and his son Vittorio Emanuele II (1820-78) were also pragmatists, navigating the variable politics of their own and neighboring realms—especially during the revolutionary surges of 1830, 1848 and after. The Catholic Church was an entrenched presence at home in Savoy, with a grip on the affairs of every diocese and parish. It was also a major territorial power in Italy and an inevitable opponent of their nationalist project.

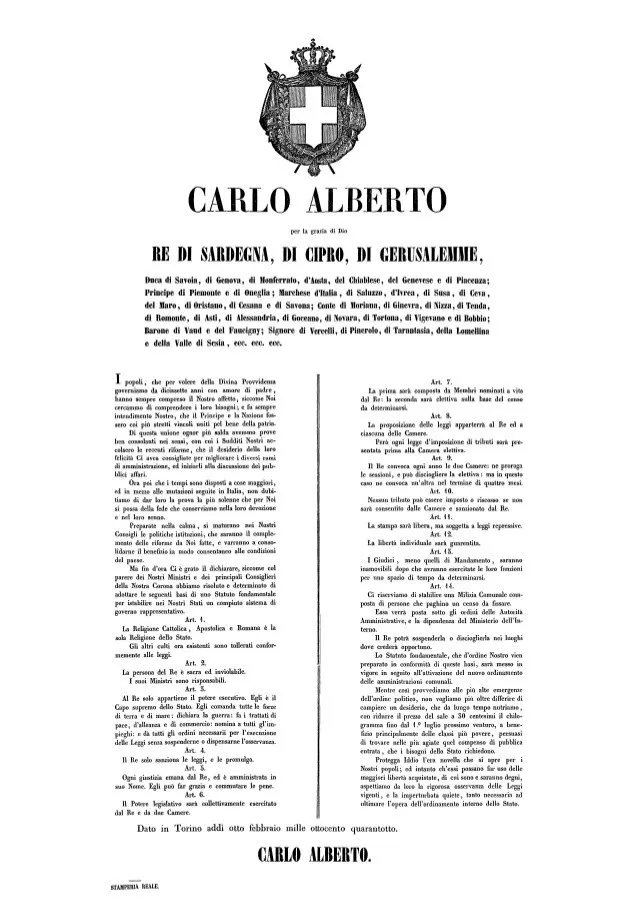

On 8 February 1848, in the seventeenth year of his reign and only months after the appearance of Tedeschi’s panegyric, Carlo Alberto di Savoia published the first draft of a quasi-constitution for his kingdom—promoting religious toleration as the hallmark of his regime:

"Now that the times have prepared yet greater things, in the midst of changes in Italy...we have resolved and determined to adopt the following tenets of a Fundamental Statute, in order to establish a complete system of representative government: Article 1. The Catholic, Apostolic and Roman Religion is the sole Religon of this State. The other cults that now exist are tolerated in conformity with the laws."

"Ora poi che i tempi sono disposti a cose maggiori, ed in mezzo alle mutazioni seguite in Italia...abbiamo risoluto e determinato di addottare le seguenti basi di uno Statuto fondamentale per istabilire nei Nostri Stati un compiuto sistema di governo rappresentativo: Art. 1. La Religione Cattolica, Apostolica, e Romana è la sola Religione dello Stato. Gli altri culti ora esistenti sono tollerati conformemente alle leggi."

A few weeks later, on 4 March 1848, Carlo Alberto promulgated a fuller and more robust instrument of government, known in history as the Statuto Albertino (Albertine Statute):

"Today we come to fulfill what we announced to our beloved subjects with our proclamation of the past 8 February...as the fundamental, perpetual and irrevocable statute and law of our monarchy, as follows: Article 1. The Catholic, Apostolic and Roman Religion is the sole Religon of this State. The other cults that now exist are tolerated in conformity with the laws."

"Noi veniamo oggi a compiere quanto avevamo annunziato ai Nostri amatissimi sudditi col Nostro proclama dell' 8 dell'ultimo scorso febbraio...abbiamo ordinato ed ordiniamo in forza di Statuto e Legge fondamentale, perpetua ed irrevocabile della Monarchia, quanto segue: Art. 1. - La Religione Cattolica, Apostolica e Romana è la sola Religione dello Stato. Gli altri culti ora esistenti sono tollerati conformemente alle leggi.

"Tolerate" was a very big word in that day and age, since few were ready to claim that all faiths were created equal. Carlo Alberto reiterated his previous language, but what did it really mean? Did those other "existing cults" include non-Christian ones or only Waldensian Protestants? Then what about the "laws" to which these various believers were expected to conform?

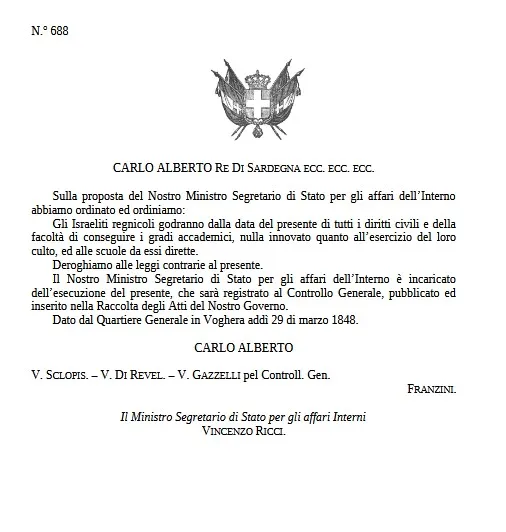

Three weeks later, on 29 March 1848, Carlo Alberto finally said the word "Jews" (or rather "Israelites") when he issued Royal Decree Number 688:

As proposed by our minister, the State Secretary for Internal Affairs, we have ordered and now order that:

As of this present date, the Israelite nationals of this kingdom [israeliti regnicoli] will enjoy all civil rights and the ability to obtain academic degrees, without infringing on the practice of their religion [culto] and the schools [scuole] which they manage.

We abrogate any laws contrary to this.

Our minister, the State Secretary for Internal Affairs, has been charged with putting the present ruling into effect. It will be recorded in the General Register, then published and included in the Acts of our Government.

This Royal Decree appeared as both an executive order and an administrative clarification, evidently urged by Vincenzo Ricci, the king's Secretary of the Interior. Article 24 of the Statuto Albertino already spelled out the "rights and duties of citizens" [dei diritti e dei doveri dei cittadini], stipulating that "all nationals of this kingdom [regnicoli], whatever their title or rank, are equal before the law. All equally enjoy civil and political rights, and can be admitted to civil and military positions, apart from those exceptions prescribed by law".

But were Piedmontese Israelites in fact "nationals of this kingdom"? Jewish "toleration" could not be seen as settled law, while older discriminatory legislation remained on the books. In regard to the independence of "the schools which they manage", the reference is to places of worship ("scuola" being the preferred term for "synagogue").

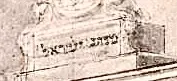

As it happened, the first Jew to take a university degree under the new dispensation (in Turin in 1849) was none other than Marco Tedeschi, recent author of the Hymn of the Piedmontese Isralelites. He later went on to become Chief Rabbi of Trieste, then an Austro-Hungarian protectorate.

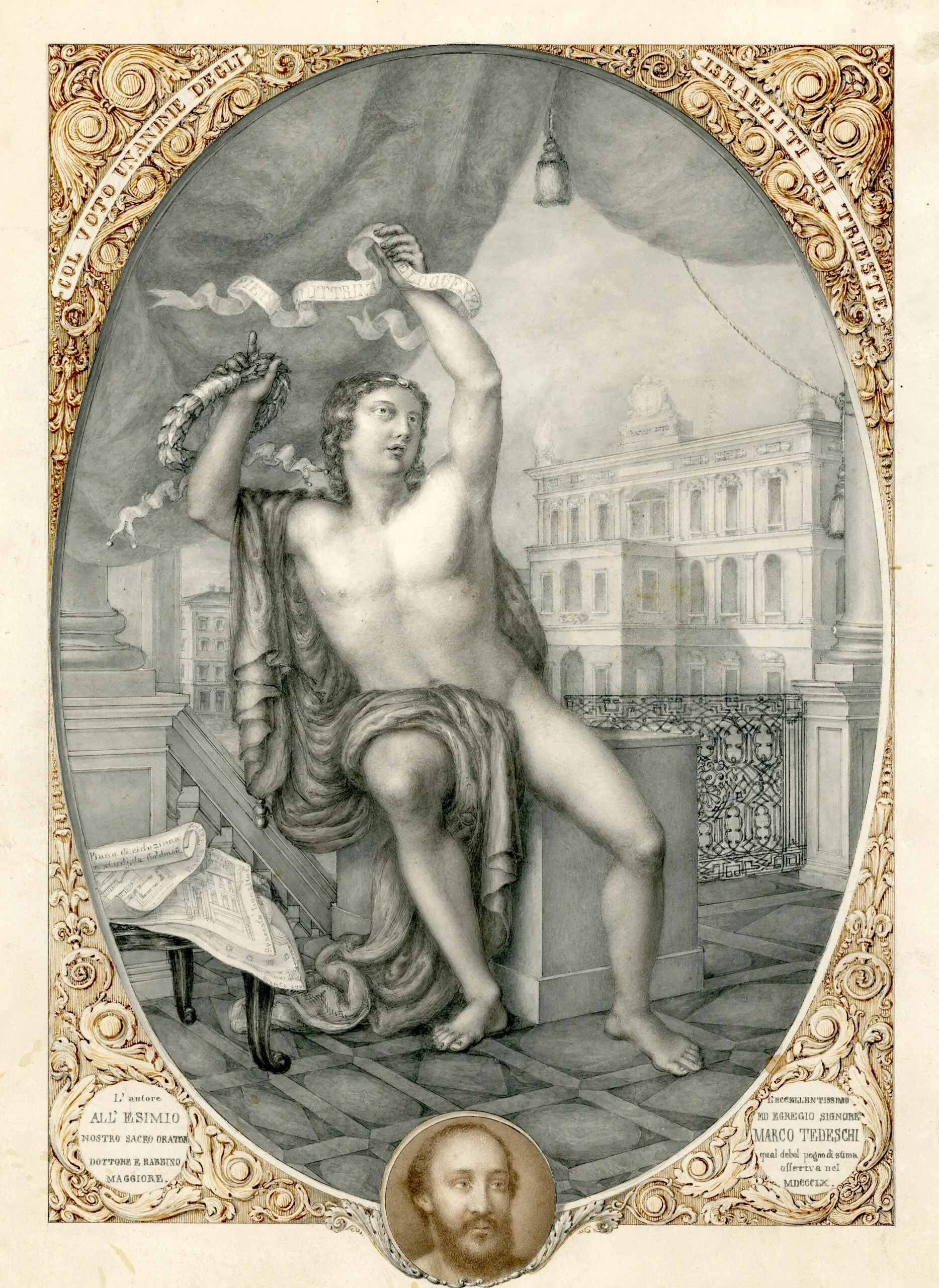

"WITH THE UNANIMOUS CONSENSUS OF THE ISRAELITES OF TRIESTE, From the author to our singular sacred spokeperson, doctor and high rabbi, the excellent and distinguished gentleman MARCO TEDESCHI, this inadequate pledge of esteem was offered in 1860."

An unidentified but accomplished member of Trieste's Jewish community created this startling document of Italian acculturation as model for a print or simply a presentation piece in its own right. The classicizing nude brandishes both a garland and a scroll reading PIETÀ, DOTTRINA, ELOQUENZA (Piety, Doctrine, Eloquence), in a triumphant pose that echoes the liberation from bonds. The grand building in the background, perhaps an aspirational synagogue unlike any yet realized in Italy, bears a two-word legend; the second word is clearly YISROEL (Israel) while the first word is less easy to parse.

As we might expect, Tedeschi was a passionate advocate of Italian Unification under the auspices of the House of Savoy, popularly known as "Cavour's Rabbi" (referring to Camillo Benso, Conte di Cavour, Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia and chief architect of Risorgimento policy).

"Discourse recited by the Most Excellent Gentleman Marco Tedeschi, Professor of Literature and formerly Rabbi in Asti, on his solemn accession to the position of Chief Rabbi of the Israelite Community of Trieste, in the Great Temple of the German Rite, on the evening of 4 Chislev 5619-11 November 1858". This copy of the Discorso is inscribed to "Domenico Berti, Deputy in the Italian Parliament...by the author, Professor Marco Tedeschi". (Harvard University Library)

Marco Tedeschi's academic title was a proud emblem of his place in a new and more humane society where he played a leading role. According to an old and evidently true story, Tedeschi was offered the position of Chief Rabbi in both Turin and Trieste, but opted for the latter at Cavour's urging—thereby deploying an influential ally in that Italian-speaking Habsburg city.

During the turbulent years of the Risorgimento, the House of Savoy's benevolent treatment of Jews demonstrated their enlightened values and readiness to govern in a modern world. That, however, was only one aspect of the "Jewish Question", which was inextricably twined with the "Roman Question". The Eternal City was both the natural capital of a United Italy and the age-old seat of the Catholic Church, with its dire history of bigotry and oppression.

(7) THE JEWISH QUESTION vs. THE ROMAN QUESTION

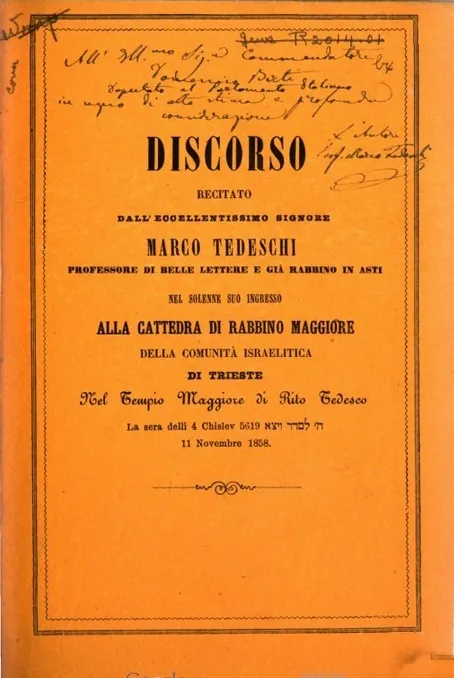

The Albertine Statute (1848) prescribed the creation of a bicameral legislature for that emerging kingdom. The Camera dei Deputati (Chamber of Deputies, locally elected in the various constituencies) met in Palazzo Carignano while the Senato (Senate, with members named by the king) had larger and even grander premises in nearby Palazzo Madama.

The Subalpine Parliament (as it was known) was a model legislature, demonstrating the values of representative government in an expanding constitutional monarchy—one that was eager to absorb other Italian territories amidst the profound "changes" of the day. A vigorous airing of views was encouraged, especially in the Chamber of Deputies. Deliberations were duly recorded and published, offering a riveting account of that tumultuous time.

In the Chamber, one of the more outspoken progressives was Giovan Battista Bottero: medical doctor, journalist and liberal deputy from Nizza (now Nice in France). Bottero could always be counted on to provoke his fellow delegates, enlivening their technical discussions of policy. His contribution on 9 June 1858 was a case in point.

PRESIDENT: I ask if the motion by the Honorable Deputy Castagnola has been sustained?

(It is sustained.)

General discussion is now open regarding this proposal.

Deputy Bottero has the floor.

BOTTERO: I asked to speak because the honorable gentleman who previously expressed his opinion referred to the decree that one of the Itailian governments is soon to promulgate. This is a law which threatens to confiscate the property of citizens who are naturalized elsewhere, with other possible penalties as well.

I am well informed, so I can assure you that this imminent decree is already causing astonishment and indignation throughout the world. That potentate's motives must be revealed here, since there is no other Italian parliament where such oppression can be stigmatized as it deserves.

Stefano Castagnola, like Bottero, was a radical progressive and avowed anticlerical. In his address, he described an Italy that was changing shape, with a mobile population gravitating toward more liberal and forward-looking jurisdictions (especially the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia). The tiny and less advanced Dukedom of Modena struggled to hold the line, penalizing those who would jump the narrow borders of their already fragile state. Castagnola urged the Subalpine Parliament to establish clear legal criteria for granting sanctuary to worthy Italians from elsewhere.

For Deputy Bottero, this pending legislation encapsulated a far bigger issue—the devastating influence of the Roman Church on Italian politics and daily life.

BOTTERO: In Modena, there have been many cases of Israelite children baptized by a male or female servant, whether out of revenge, stupidity or fanaticism. This would scarcely matter if such an illegal act had no outcome beyond a little water sprinkled by some irrelevant person. However, as soon as the manservant or housemaid reports this bit of poured liquid to the police, all the rest ensues. Dragoons invade the house, tear the child away from its family and carry it off to be raised as a Catholic. This outrages the purest feelings of nature and the most elementary rules of morality, while inflicting the gravest oppression that man can imagine.

(NOISES FROM THE RIGHT)

In Turin's Chamber of Deputies, the delegates were seated according to their political persuasion, so "noises from the right" meant exactly that—protests from the Catholic conservatives. As a veteran journalist, Bottero knew how to elicit reactions, political and otherwise. For ten years, he had been a mainstay of La Gazzetta del Popolo (The People's Gazette), an authoritative voice of liberal, anticlerical and nationalist sentiment in Piedmont and beyond.

BOTTERO: From what I witness on the benches before me, I suspect that someone might want to contest the facts that I am presenting.

In order to save my adversaries such effort, I will say immediately that I have been fully informed and have seen the relevant documents. These were furnished by those in Modena of the Israelite faith, who exhorted me to reveal this egregious scandal.

Are you asking to hear more? In Turin, there is presently an Israelite family that had to flee Modena in terror, smuggling out a little girl. They feared that she would be seized because a servant girl claimed to have baptized her.

(SENSATION)

BOTTERO: The Modenese Government saw that rich and educated people, like these Israelites, were leaving the Dukedom for these very reasons, not to mention other restrictions worthy of the Middle Ages. They sought to transfer their capital elsewhere and then bear witness to a level of oppression equaled only in barbarous times. This induced the Modenese Government to draw up the decree that the Honorable Deputy Castagnola discussed with you.

BOTTERO: In sharing these facts with Parliament, I do not seek to strengthen a proposed law, since that law requires no special pleading. The patriotic spirit lodged in the heart of everyone here insures that it will be adopted. I spoke as my conscience dictated and as I had been implored by those who groan under savage oppression due to their religion. Especially now in the Nineteenth Century and especially here in Italy's sole Parliament, such an outrage to the laws of nature and morality deserves to be stigmatized. Only here is speech still free, thanks to the energy of the people and the loyalty of their Prince. Only here can we vindicate the honor of the rest of the nation, while vindicating the laws of morality and nature.

("BRAVO!" ON THE LEFT)

(NOISES ON THE RIGHT)

CAVOUR, President of the Council [of Ministers], Minister of Foreign Affairs and Minister of the Interior: Gentlemen, if the issue that is now being submitted to this Chamber consists in deciding whether it is necessary to begin immediate deliberation of the proposal made by the Honorable Deputy Castagnola...

Giovan Battista Bottero built up a fine head of steam, eliciting the reactions he desired on both sides of the room. Count Camillo Benso di Cavour, a staunch nationalist but far from an extremist, could then proceed to the legislation at hand without acknowledging his colleague's explosive Jewish advocacy.

Bottero was well-informed, thanks to Jewish connections who supplied him with the latest news. In only two weeks, his vivid warning of 9 June 1858—recorded for posterity in the acts of the Turin parliament—would emerge as one of the most prescient documents in the history of the Risorgimento.

(8) MORTARA BEGINS

On the night of 23 June 1858, a sensational parallel story broke in Bologna—the second city of the State of the Church, governed by the Pope's own Cardinal-Legate. The papal police had stormed a Jewish home and removed a six-year-old boy, Edgardo son of Momolo and Marianna Mortara—allegedly baptized by a Catholic maidservant five years earlier.

The case had been in the works for about a year at the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Rome—and there was even a Modenese connection. Momolo and Marianna emigrated from Reggio Emilia in the Dukedom of Modena a decade before, along with others of their community.

Bologna, only 50 miles (79 kilometers) away, was a much larger place than either Modena or Reggio, offering more economic opportunities. While the territory was in the firm grasp of the papal regime, there was no established Jewish presence nor had there been for three centuries. The new arrivals might have hoped—against the odds—that they could keep a low profile and get on with their lives.

The Mortara kidnapping could not have been a total surprise for many or most people at that time. For centuries, the Catholic Church had exerted the utmost pressure on Jews to convert, using every tactic at their disposal. One of the earliest and now best-known representations of the Mortara sequester is by the German Jewish painter Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800-80). By 1862, the case had already been widely reported around the world, so Oppenheim had a mass of facts and fantasies from which to work, as well as an age-old store of his people's lived experience.

Oppenheim shows us (from left to right) a solicitous nun, an official messenger (in livery, standing under a mezuzah on the door-jamb), an insinuating monk (in a brown Franciscan habit) and the six-year-old Edgardo Mortara (barefoot and wearing a junior tallit). A smug priest (in coal-shovel hat) wards off the desperate father, while the stricken mother faints into the arms of her daughter and her son raises a fist in futile protest. At the far edge of the scene, a servant girl breaks down in tears in a shadowy doorway.

The nun, the priest and the monk are only notional. Father Pier Gaetano Feletti, the local Inquisitor (a white-clad Dominican, in fact) sent in the civil authorities to do the dirty work. The distraught maidservant is a nice narrative touch, but Anna Morisi—the one who caused the trouble—was already long-gone from the Mortara household.

A century and a half later, director Marco Bellocchio offered a more factual cinematic recreation of the event, set in a plausible middle class home of that time. (Momolo Mortara traded successfully in upholstery supplies.) Marshall Pietro Lucidi appears at the left of the still, representing the Papal Police but in civilian clothes. Meanwhile, a detachment of uniformed constables waited on the stairway and out in the street.

Lucidi insisted on seeing all five of the Mortara boys, some of whom were already in bed asleep. (There were also three girls, including a pair of twins.) Then he made the polite but chilling announcement that found its way into the movie script, "Signor Mortara, I am sorry to tell you that you have been the victim of a betrayal. Sir, your son Edgardo was baptized. I am ordered to take him." ("Signor Mortara. Sono dispiacente di significarle che Ella è rimasta vittima di un tradimento. Suo figlio Edgardo è stato battezzato. Ho ordine di prenderlo".)

In the State of the Church, the civil authorities operated under direct ecclesiastical control. For Feletti and by extension Lucidi, there were two essential considerations—regarding the nature of baptism in general and the Mortara baptism in particular. By Church law and custom, young children like Edgardo could not be baptized without their parents consent, except in special circumstances—like a medical crisis that threatened imminent death and eternal purgatory for the unredeemed soul.

A much-contested account of the purported baptism emerged in the months and years to come, as the Mortara Case worked its way through religious and civil courts—also the court of public opinion.

The maidservant Anna Morisi, an illiterate peasant girl in her mid-teens, allegedly witnessed an alarming scene—Momolo and Marianna reading incomprehensible Hebrew over the baby Edgardo, then about a year old.

The imaginative Morisi took this to be the Jewish version of last rites for the dying. Edgardo was indeed ill, but only mildly according to the family doctor, with a normal childhood ailment.

Morisi conferred with a neighborhood grocer named Cesare Lepori, who suggested that the girl baptize the child in extremis—on her own. All she needed to do was gain access to the baby, sprinkle a few drops of water on his head and say, "I baptize you in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost."

And thus it was done. But Edgardo failed to expire, recovering quickly and embarking on a healthy childhood. So, Morisi banished the incident from her mind, until karma, history or whatever else caught up with her a few years later.

Morisi had leaked the story of her impromptu baptism to a friend and the friend eventually talked. Word then reached the Father Inquisitor in Bologna, who referred the matter to the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Rome, which referred it back to Bologna—with an order for immediate action.

The film makes dramatic use of popular prints of the time. Here we see, "IL PAPA RAPITORE / THE KIDNAPPER POPE", showing (left to right): Cardinal Giacomo Antonelli, Papal Secretary of State (making a furtive exit), Pope Pius IX (clutching the screaming boy), an unidentified clerical figure (running behind with biretta in hand, perhaps the Cardinal-Legate of Bologna) and a view of that city in the distance.

Pius IX and his fellow travelers were blindsided by the vehement international reaction to the Mortara Case. They were operating beyond the limits of their personal and institutional experience—in a strange new world where the Church was expected to account for its actions.

Baptism for them was eternal and irreversible, whatever the circumstances. Since Edgardo was now Catholic, there was nothing to discuss—except removing him from the influence of his Jewish former family.

In an unforgettable juxtaposition of scenes, the film shows an emergency convocation of Bolognese Jews. The camera focuses on a table heaped with publications, including satirical prints that savaged the Mortara kidnapping. Then soon after, we see Pius IX in all his splendor but oddly vulnerable, poring over the same articles, cartoons and broadsides.

No one could have been prepared for the furor that erupted in the wake of the Mortara kidnapping. The story broke suddenly and furiously around the world, propelled (at least in the early stages) by a largely unsuspected network of Jewish organizations and individuals.

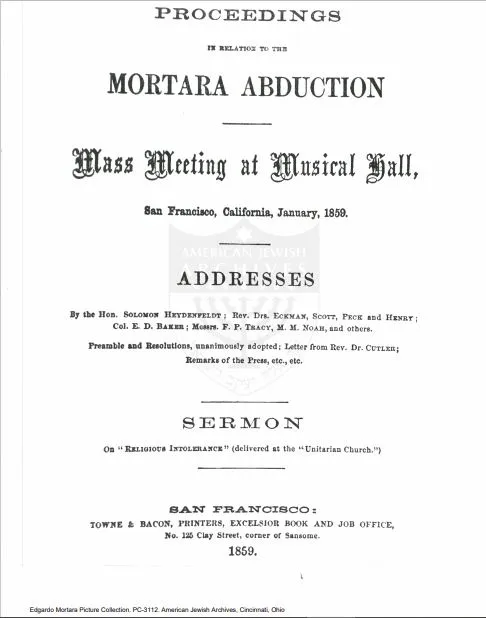

Case in point: On 15 January 1859, seven months after the fateful knock on the Mortaras' door, there was a lively protest meeting half-a-world away in San Francisco, California. That rambunctious post-Gold Rush town was still assimilating its oddly-assorted population of economic opportunists, political adventurers and religious freedom-seekers (including many who were all three at once).

The two lead-off speakers were both Jews, but the event also attracted an impressive range of liberal (or at least Anti-Catholic) Christians. The Honorable Solomon Heydenfeldt chaired the meeting. A lawyer rom Charleston, SC, he practiced in Alabama for some years, before moving to California in 1850. He was admitted to the state bar in 1851, then in 1852 became the first popularly-elected Jewish Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. Heydenfeldt served there until 1857, when he joined a lucrative law practice in San Francisco, but was forced to retire in 1862. A pro-slavery Southerner born and bred, he refused to take a loyalty oath to the Union Government.

The Reverend Doctor Julius Eckman, an ordained rabbi, evidently laid the groundwork for the event. Born in Rawicz in formerly Polish East Prussia, he studied in Berlin and then moved to the American South in 1846, leading congregations in Mobile, New Orleans and Charleston (he and Heydenfeldt certainly knew of each other and quite likely crossed paths.) In 1854, Eckman settled in San Francisco, where he ministered as a rabbi and—no less relevantly—founded an English-language Jewish newspaper.

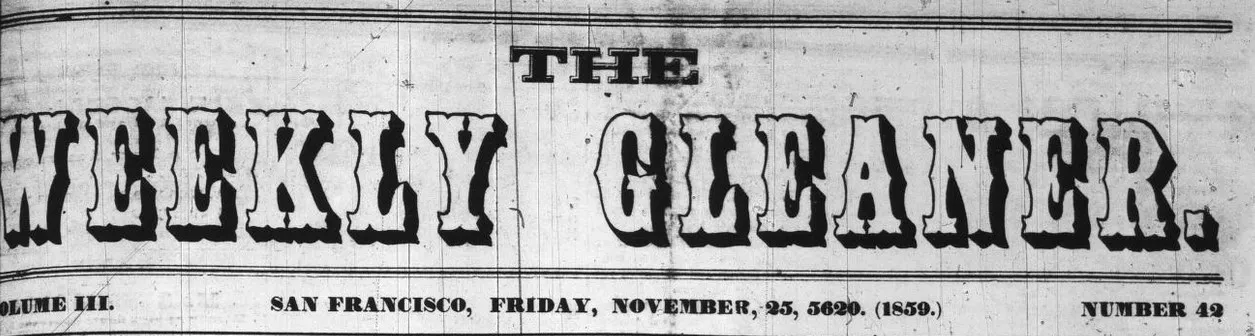

THE WEEKLY GLEANER is now valued as the chief early source for Jewish affairs in the American West, published regularly since 1857 (later amalgamated with San Francisco's Jewish Chronicle). Eckman's journal arrived on the scene just in time to cover the rapidly expanding Mortara Case, culling other publications from around the world.

On 25 November 1859, The Gleaner (p.2) channeled Les Archives israélites de France (a monthly journal founded in Paris in 1840) by way of The Jewish Chronicle (published weekly in London since 1841). An unidentified correspondent reported to the Archives on the activity of the eighty-year-old SIgnor [Lazzaro] Carpi of Bologna. In February 1859, in the dead of winter, he undertook "a tour in Italy on behalf of the unfortunate Mortara family. Wherever he went he was received with the greatest sympathy. Considerable sums are the results of this journey; they will be applied for the support of this noble cause."

In the usage of the time—in more advanced circles at least—"Italy" was the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia (not merely "a geographical expression", as Metternich would have had it a generation earlier). If progress was to be made in the Mortara Case, it would be by way of Turin, not Bologna or Rome, since Pius IX had shut down any possible negotiation.

Alessandro, one of Lazzaro Carpi's seven sons, accompanied him on his travels. Another, Leone Carpi (1810-98) was already famous and based in Turin, working closely with top nationalist leaders. In August 1858—only two months after the kidnapping—the Jewish communities of Piedmont-Sardinia held an emergency meeting in Alessandria to formulate a response. With Leone's help, they appealed directly to the governments of France and Britain, seeking their intervention. In 1860, Leone became the first Jewish member of the Chamber of Deputies, as soon as his native province of Ferrara was incorporated into the Kingdom of Italy.

The Catholic regime had long viewed the elderly Lazzaro Carpi as a dangerous radical, heading a family of known subversives—but by 1858, their activism had entered the political mainstream of a revolutionary age.

As widely reported, Lazzaro Carpi bolstered his personal testimony with a range of relevant documents. This included a letter from Momolo Mortara recounting a heart-rending meeting in Rome with the stolen Edgardo. "After they left the room this poor child ran after them, clinging with all his force to his mother, from whom he had to be torn. It is proved that no means were spared to induce Mortara himself to embrace Catholicism."

In another article on the same page of The Weekly Gleaner, Eckman updates his readers on reactionary Catholic opinion in France by an equally circuitous route. "Of all the fanatics of modern time, of whom we so frequently made mention while treating on the Mortara affair, none has attained to such an uneviable notoriety as M. Veuillot, editor of the French ultramontane journal the Univers. His attacks against Protestants and Jews are especially virulent."

How did did Eckman arrive at his story? In 1858, Gustave Vapereau—a Parisian liberal—published the Dictionnaire Universel des Contemporains, a chatty biographical guide to the notable figures of that day. Louis Veuillot—a crazed Jew-hater and papal apologist—received brief if scathing treatment (pp.1722-23). Then the following year, Vapereau's exposé was amplified in a book review in The Athenaeum (March 12, 1859, p.353), a distinguished London weekly, "Perhaps the most curious biographical article in this volume is that of the notorious fanatic Veuillot..."

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.