GARIBALDI & GOLDBERG LAND IN SICILY: A Jewish View of the Italian Risorgimento (Part 4)

CONTENTS:

(9) PAPAL FALLIBILITY

(10) MORE MORTARA: The Pope and His Inquisitors Go to Cincinnati

(11) MORE PAPAL FALLIBILITY

(9) PAPAL FALLIBILITY

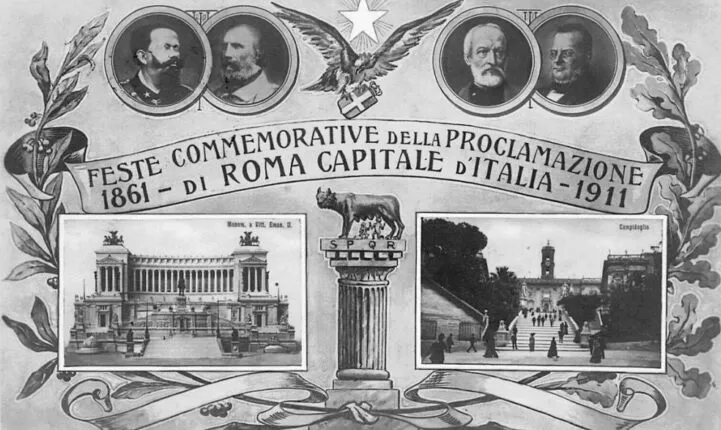

Hindsight is a funny thing. A United Italy based in Rome now seems a historical inevitability, which it probably was. Still, the crucial pieces would not have come together when and how they did, if "The Roman Question" had not collided with "The Jewish Question" at exactly the right moment—with the Mortara Case at its crux.

.webp)

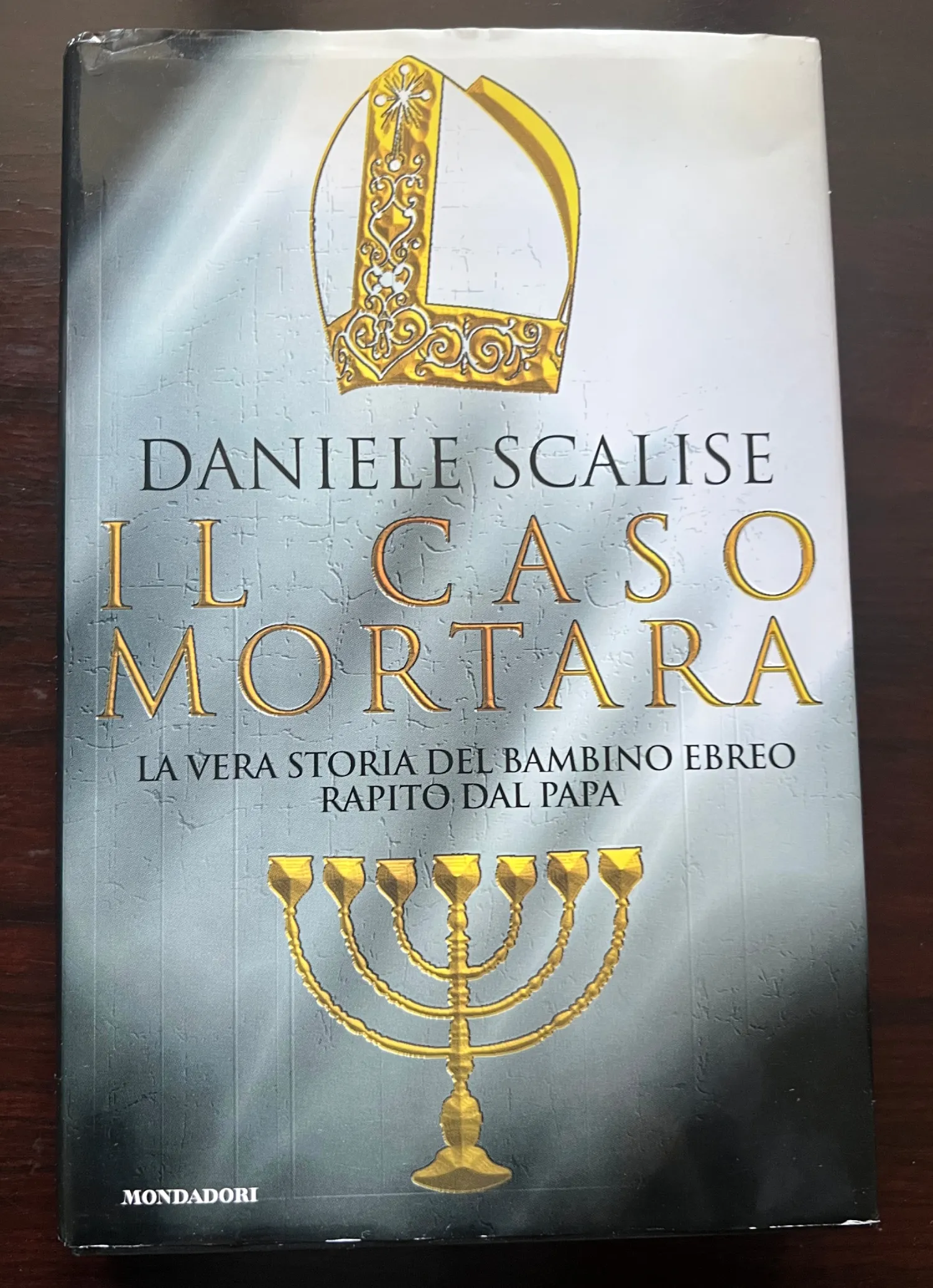

In his essential book, The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara (1997), David Kertzer offers a telling assessment of the state of play in Italy and beyond in the wake of the Mortara kidnapping.

"In the past, neither governments nor non-Jews had shown any interest in the problems Jews of other countries faced as they dealt with the power of the Church. But in 1858 the international situation was dramatically changed. The debate over the continuing temporal power of the papacy, and hence the wisdom of a theocratic state in the middle of Europe was reaching a fevered pitch." (Kertzer, p.85)

Then Kertzer again, at his most direct, insightful and mind-bending:

"Could the story of an illiterate servant girl, a grocer and a little Jewish child from Bologna have altered the course of Italian and Church history? The question is not nearly as far-fetched as it appears. A case can be made that Anna Morisi—sexually compromised, dirt-poor and unable to write her own name—made a greater contribution to Italian unification than many of the Risorgimento heroes whose statues preside over Italian town piazzas today." (Kertzer, p.173)

As the Mortara Case jolted along—subsuming many of the weightiest political and moral issues of that time—the Jews in Bologna played their last card in hope of retrieving little Edgardo. They could not dispute the inherent character of baptism, so they sought to prove that no baptism had taken place, not even a frivolous misguided one.

Impeaching the witnesses was their chief strategy. Did the grocer Cesare Lepori actually instruct the maid servant Anna Morisi on the practicalities of that sacrament, which she was too ignorant to know on her own? Could anything that Morisi said be believed, since she was an immoral slut who slept with any and all of the Austrian soldiers who patrolled the city of Bologna at the Pope's behest?

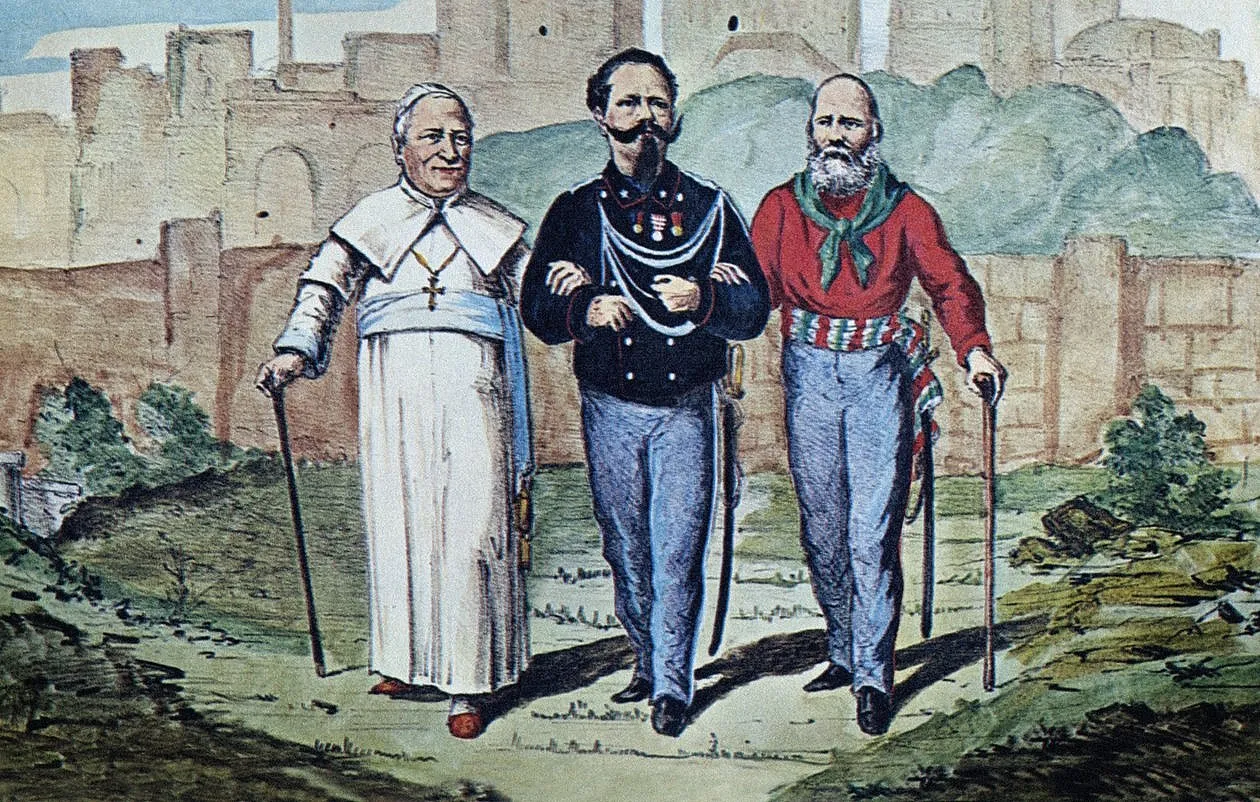

We run into much that is strange but true while tracking the Mortara Case but also much that is utterly preposterous, especially in the wake of Risorgimento mythmaking. Can we—in our wildest dreams—imagine Pope Pius IX, King Vittorio Emanuele II and Giuseppe Garibaldi arm-in-arm outside the walls of Rome, striding boldly into the future of a United Italy?

In 1859, Pius IX excommunicated Vittorio Emanuele II and his confederates (Cavour included) after they annexed most of the State of the Church. In 1870, following their conquest of Rome, he declared himself the “Prisoner of the Vatican” and played that desperate role to whatever effect he could.

In 1862, Vittorio Emanuele II banished Giuseppe Garibaldi to a remote island off the coast of Sardinia, when he refused to abandon his military campaign and support the king's diplomatic machinations. The Hero of the Two Worlds then popped in and out of exile for the rest of his life.

At times, the Unification of Italy progressed slowly if it progressed at all. Then huge pieces fell into place—apparently over night, with a seeming will of their own.

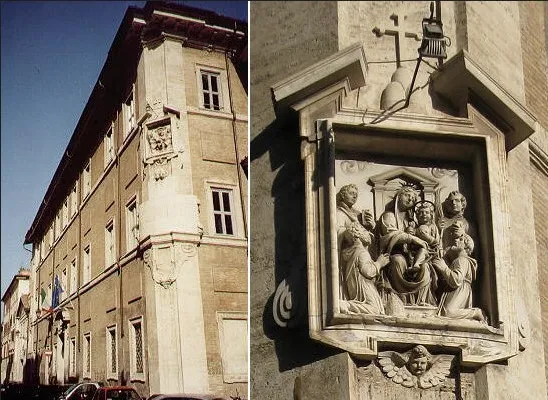

The Papal State had long been untouchable, since the Congress of Vienna (1815) at least. This huge swathe of land ran for 500 kilometers (300 miles) from the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, through Umbria (Orvieto, Spoleto, Perugia), to the Marche (Ascoli, Camerino, Fermo, Macerata, Urbino, Ancona, Pesaro), to the Romagna (Forlì, Ravenna, Ferrara and Bologna). Only six of these territories (Velletri, Frosinone, Rieti, Civitavecchia, Viterbo and Rome) were in Lazio, the Church's territorial homeland, in a venerable conglomeration of mostly medieval donations known as the "Patrimony of Saint Peter".

As Pius IX knew—or at least suspected—his grasp on many of these districts was tenuous at best, especially the “Legations” (governed by Papal Legates) in the north and along the Adriatic coast (Bologna included). The people there had histories, cultures and customs of their own—but little affection for their Papal overlords, especially in a new age with the Pope's ancient mystique dissolving before their very eyes.

Liberals throughout the region were demanding (as yet) moderate reforms but the current of unrest ran deep. The great city of Bologna had already expelled its Roman rulers—albeit briefly—during the revolutionary upheavals of 1848-49. Pius IX then borrowed Austrian troops to secure the town and they had remained there ever since.

If Pius IX had not been Pius IX, he might have defined a cautious middle path, possibly saving his territorial state. Instead, he opted to stare down his restive subjects. From 4 May through 5 September 1857, he effected a long and lumbering progress through the Legations, unleashing the full force of his power and charisma—in theory at least.

Pius IX spent several weeks in Bologna, his chief subject city, blocking any attempt at civil negotiation. The Pope's intransigence seemed principled to some, but it was not a winning strategy. Even his calmer supporters soon learned that getting rid of Pius IX was easier than trying to talk to him. Then a year later, the Mortara Case exploded on 28 June 1858.

On 21 July 1858—just a few weeks after the knock on the Mortara's door—Napoléon III, Emperor of the French, and Camillo Cavour, Prime Minister of Piedmont-Sardinia, met secretly at Plombiéres, a quiet spa town in the Vosges mountains of France.

Their briefly top-secret agreement was to launch a war with Austria. Along the way, Piedmont-Sardinia would gain Austrian-held Lombardy and Venetia, as well as the independent dukedoms of Parma and Modena. Meanwhile, Piedmont-Sardinia would cede Savoy and Nice to France.

%20enhanced.webp)

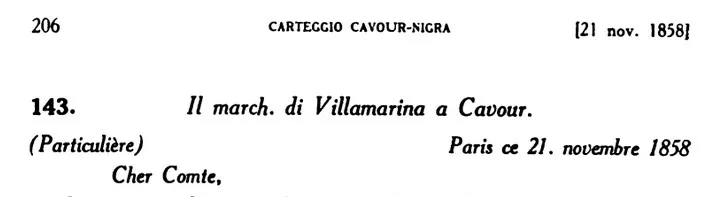

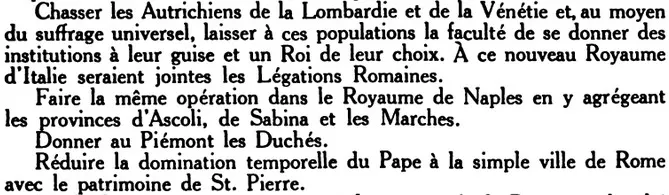

On 21 November 1858, four months after the Plombières conference and five months after the Bologna kidnapping, the Marchese di Villamarina (Piedmontese Ambassador in Paris) shared the latest news from Rome with Prime Minister Camillo Cavour, as relayed by the Duke de Gramont (French Ambassador at the Papal Court).

According to Gramont, Pius IX had much to say regarding the Mortara Case—but that was only the beginning. (The Piedmontese administration often favored French in their records and correspondence. Italian would remain a second language for many, including Camillo Cavour.)

Monsieur de Gramont, for his part, recently had some intense and rather bitter exchanges with His Holiness and State Secretary [Cardinal Giacomo] Antonelli. The subject was the matter of the young Mortara. The Pope showed himself to be very distressed by this incident, wishing above all that it could have been avoided and blaming it on the imprudent zeal of Cardinal Viale-Prelà [Legate in Bologna]. “At this stage, however, there is no remedy and I cannot undo what the institutions of the Church have compelled me to effect.”

Considering Pius IX's otherwise unfailing obstinacy on the Mortara issue, it is hard to credit his expression of "regret"—but for what exactly, certainly not the baptism itself? Maybe this was only a diplomatic feint, saying "yes but no" before shutting down the discussion.

Monsieur de Gramont then observed, with all respect for His Holiness, that public indignation in France was too strong for Emperor Napoléon and he could not overlook such a violation of civil and natural law. His Holiness replied, “I would prefer that you helped me, Ambassador, to demolish the rumors that are circulating in my own states. These rumors are substantiated by materials seized by my agents, which expose all of Emperor Napoléon’s intrigues in Italy. Here are the details of the Emperor’s plan.”

The scheme, according to Pius IX, was for France and Piedmont-Sardinia to:

Expel the Austrians from Lombardy and Venice, then allow the populace to assign the institutions of government, in such form as they wish, to a King of their choice. The Roman Legations [from Ferrara through Forlì] would be added to this new Kingdom of Italy.

Enact the same scheme in the Kingdom of Naples, attaching also the provinces of Ascoli, the Sabines [in northeastern Lazio] and the Marches [from Pesaro through Ascoli].

Give the Dukedoms [of Parma, Modena and perhaps Tuscany] to Piedmont.

Reduce the temporal dominion of the Pope to only the city of Roma and the Patrimony of Saint Peter [coastal Lazio].

Monsieur de Gramont appeared quite astonished by the Pope’s outburst and assured him that there was not a word of truth in all that. The Pope then instructed him to refer the matter to his sovereign and get back to him with a reply.

Gramont was an experienced diplomat, so prevarication was his second nature. All that could have surprised him was the uncanny accuracy of the Pope’s secret intelligence.

Cavour was clear-eyed on the Mortara affair, as he was on most things. He was also unfailingly well-informed, relying on his own agent in Rome (Conte Domenico Della Minerva Pes di San Vittorio, a Sardinian connection of the Marchese di Villamarina, the Piedmontese Ambassador in Paris.)

In regard to Rome, the information you send me appears perfectly accurate since it agrees with what has reached me from other sources. It is clear that Gramont is furious with the Pope and indeed the Court of Rome, having settled on the idea of seizing the Mortara boy himself and sending him on to Piedmont. Gramont confided this to Minerva and I ordered Minerva to support him, while letting Gramont play the chief role. Gramont then hesitated and probably gave up the idea on orders from Paris. The Emperor [Napoléon III] is obsessed with the Mortara affair and anything that can compromise the Pope in the eyes of Europe and of moderate Catholics. The more grievances the Emperor has to use against the Pope, the easier it will be for him to mandate the sacrifices required for the restructuring of Italy.

With this in mind, our role is quite simple. However we can, we need to emphasize the Emperor’s efforts to induce the Pope to follow a more reasonable political line. We need to exalt Gramont’s courage and energy in deploring the Pope’s conduct, thereby demonstrating the absolute impossibility of him maintaining temporal power outside the walls of Rome.

Pius IX got the facts right, but could not stop the essential process of Italian Unification—as demonstrated by two maps from only two years apart. Borders had not shifted between the Congress of Vienna in 1815 and the upheavals of 1859-61, in spite of failed insurgencies more or less everywhere in the late 1840s.

In 1859, Piedmont-Sardinia was still a relatively small territorial entity (on the peninsula, at least, with a large island attached), even after annexing the defunct Genoese Republic at the conference table in 1815. At that same time, all of Northeastern Italy (from Milan to Venice) was amalgamated into the so-called Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia, a Habsburg crown property under direct Austrian rule. Central Italy still featured several residual princely states (once there had been many more) including the Grand Dukedom of Tuscany (ruled from Florence by the house of Lorraine), the Dukedom of Parma (by the Farnese) and the Dukedom of Modena (by the Este).The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (Southern Italy and Sicily) was ruled from Naples by the Bourbons. Then there was the State of the Church.

By 1861, only the Venice part of Lombardy-Venetia (plus Mantua) was left in Austrian hands and the Pope was reduced to a middling chunk of Western Lazio (which was still a good deal more than the Vatican City we know today). Could he hold on to even that? And where in the constantly shifting political balance was the Mortara Case?

The war went badly for Franz Josef in terms of losses on the ground (both lives and territory). It went badly for Napoléon III in terms of politics back home (since French Catholics knew that the endgame was Rome and all it represented). Meanwhile, everyone feared the general instability of the time, especially in Central Europe with the potential dissolution of the Habsburg Empire.

Piedmont-Sardinia was effectively sidelined during the negotiations between Napoléon III and Franz Josef, which were stormy but anticlimactic (including Camillo Cavour’s temporary resignation in protest). On 12 July 1859, an ostensible agreement (ratified by Franz Josef) was signed in Villafranca (near Verona) by Napoléon III and Vittorio Emanuele II—usually called a “truce” or “armistice”, not a “treaty”, because no one expected it to last. In fact, Vittorio Emanuele effectively signed with his fingers crossed, appending “per tutto ciò che mi concerne” (“in so far as I am concerned”), speaking on his own behalf, not for his government—whatever that might mean in the future.

For the record and for conservative Catholic opinion, Franz Josef and Napoléon III allowed that their preferred answer to the Italian Question was a confederation of states overseen by the Pope. Then, having gotten that pious impossibility out of the way, they divided up the top half of the peninsula.

In the North, Austria would cede the region of Lombardy to France (which immediately passed it on to Piedmont-Sardinia). Meanwhile, Austria would maintain control of Venice and its territory. In central Italy, the House of Lorraine would remain in Tuscany and the Este in Modena. The State of the Church would stay intact on paper, for a while at least, although the Two Emperors tactfully advised internal reforms—which Pius IX would never countenance.

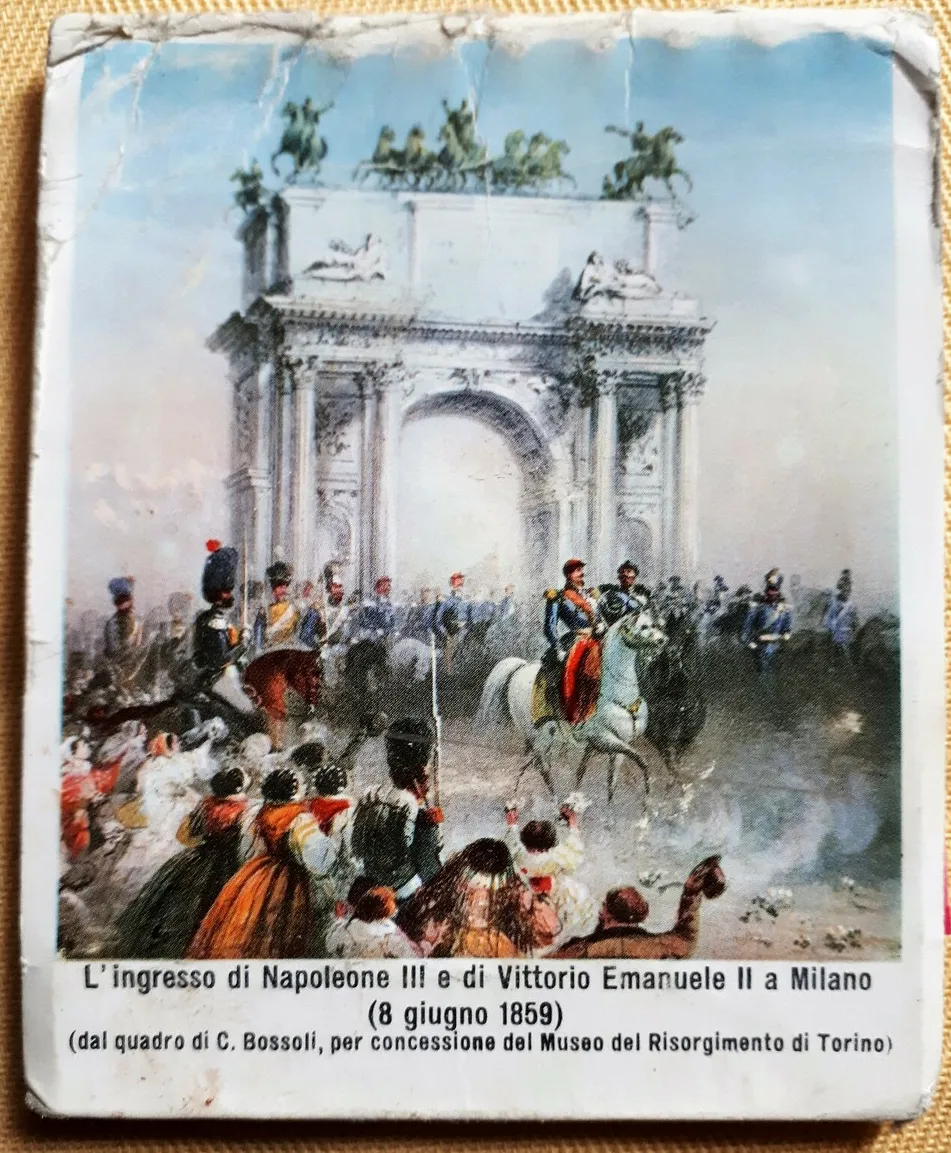

The annexation of Lombardy was the biggest take-away from the Armistice of Villafranca but that was scarcely news, since Napoléon and Vittorio Emanuele had already made a joint triumphal entry into Milan a month earlier. As expected, the direct results of the July accord were limited and fleeting, but they are not what mattered most.

On 12 June 1859, a month before the purported Armistice and four days after Napoléon III and Vittorio Emanuele II entered Milan, the Austrians withdrew their troops from Bologna. They had essential interests of their own to defend, without bogging down further in the Papal morass.

The Bolognese rose up on that very day and expelled their Roman occupiers—Legate, Inquisition and all—then offered the governance to Vittorio Emanuele II. Throughout the Legations, Papal authority was collapsing in plain sight, with the promise of more undoing to come.

While waiting for the dust to settle in Northern and Central Italy, Giuseppe Garibaldi and his Mille prepared to head south, embarking for Sicily on 5-6 May 1860. For both the friends and foes of a United Italy, the future was arriving faster than anyone could imagine.

(10) MORE MORTARA: The Pope and His Inquisitors Go to Cincinnati

One of the most compelling scenes in Rapito/Kidnapped is the storming of the Governor’s Palace in Bologna, with the camera focusing repeatedly on Riccardo Mortara, Edgardo’s oldest brother.

We can’t document Riccardo's presence there and then, but he lived nearby in the center of town. Though only in his mid-teens, he was already a patriot and would eventually become an officer in the Italian army, so it is hard to imagine him not in the thick of things.

Banishing the Papal regime from Bologna had little effect on the Mortara Case, in so far as the family was concerned. Back in the summer of 1858, young Edgardo had been spirited off to Rome and fed into the Church's conversionary machine.

Edgardo's parents were allowed limited access to him in the Casa de Catecumeni in Rome, but the boy was only six, then seven years old. Meanwhile, he faced a thorough brain-wash by the ultimate experts.

The pressure on the Pope and his minions was no less intense, as the world fixated on the case.

A few weeks after Edgardo's seventh birthday (which the Church considered the threshold of free will), he was baptized (or baptized again, depending on your reading of the original story). Whatever else, the boy was personable, smart and intellectually curious—an exceptional acquisition for the Church and an eventual asset in the public sphere.

Then there was Pius IX's emotional bond with the Mortara boy, which was a whole story of its own. Their shared plight epitomized the pontiff's struggle with the modern world, so he treated Edgardo both as a favorite toy and a heaven-sent test of faith.

“How much you have cost me and how much I have suffered for you!” Pius IX exulted to the young Edgardo on various occasions. “The great and small of this world wanted to steal this child from me, accusing me of being barbarous and pitiless. They weep for his parents but don't consider that I too am his father. No one commiserates with me in the midst of these painful trials."

Catholics and non-Catholics frequently cite these pronouncements as demonstrating either Pius IX's power of belief or his delusional self-dramatization. In any case, the chief source was Edgardo Mortara himself (later Father Pio Maria Mortara). He got with the new program in epic style, becoming as overwhelmingly Catholic as only a convert can be.

Throughout his life, Mortara did his utmost to shape his own story while furthering the cult of his late mentor Pius IX—submitting such effusions as evidence for the late Pope’s canonization (currently stalled midway). (S. R. C. Summarium super introductionem Causae Beatificationis et Canonizationis Servus Dei. Pii IX Summi Pontificis, Roma, 1954, pp.511-523.)

Whatever the forces at work, Pius IX was constantly outflanked by enemies at home and abroad. As we saw in San Francisco in 1859, word of Edgardo's abduction leapt over borders at what was then dizzying speed, triggering reactions and generating more than just news reports.

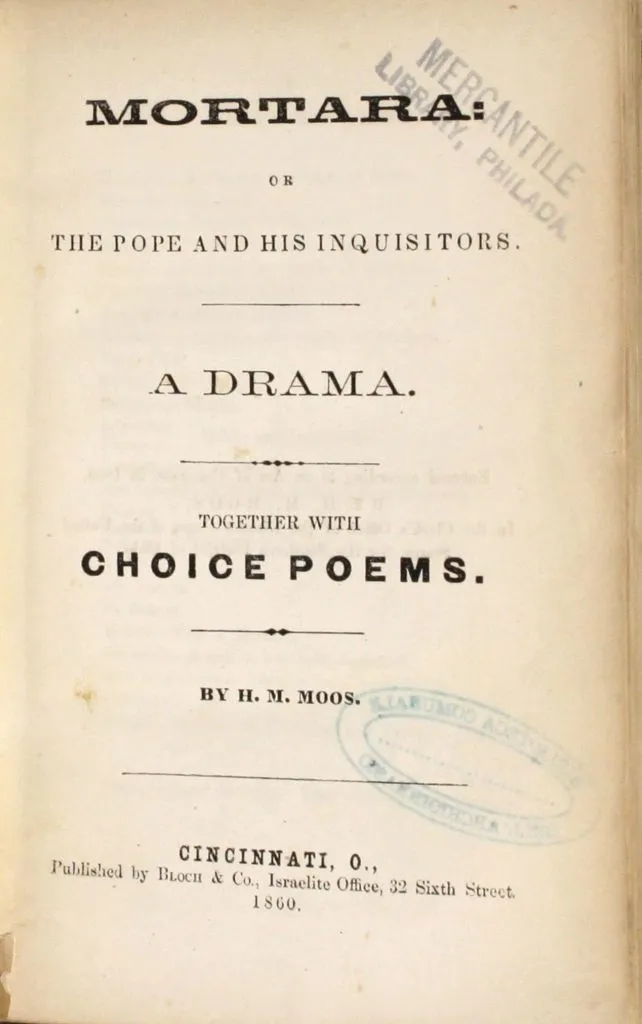

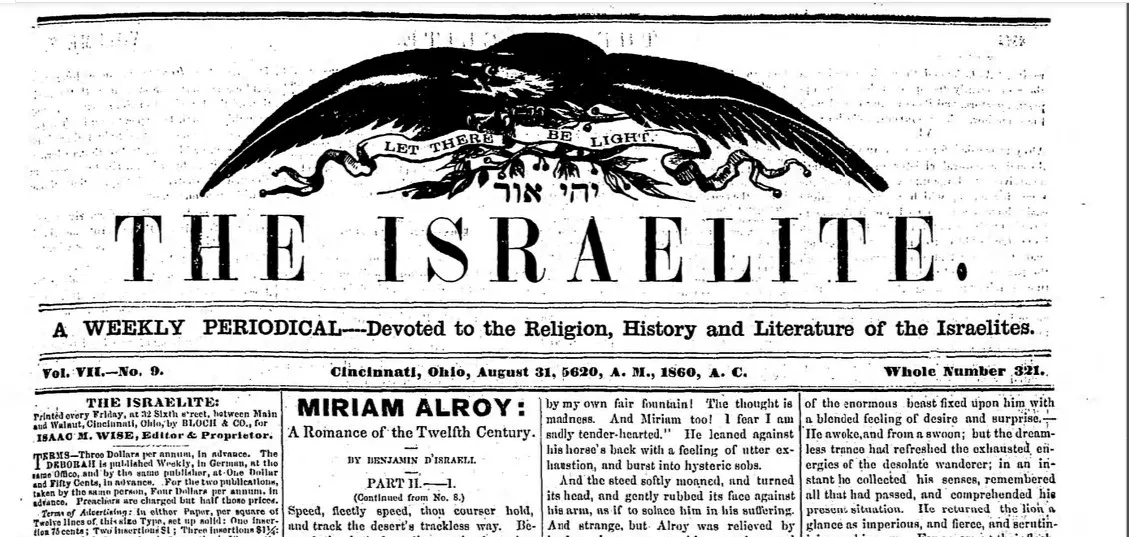

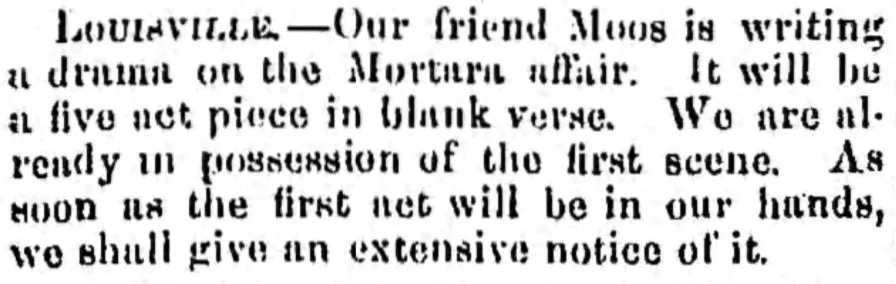

Take the case of Herman Moos, a young German-born Jew based primarily in Cincinnati, the spiritual heartland of American Reformed Judaism. In 1860, Moos published a sensational, if unstageable and often unreadable play, Mortara: the Pope and his Inquisitors (A Drama). It was published right there by Bloch & Co., the official printer of the Reformed Movement, in the office of The Israelite (later The American Israelite), their weekly newspaper.

h.

In Judaism, Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise promoted the kind of enlightened reforms that Pope Pius IX fiercely obstructed in his own realm but with a distinctly American flavor. He was also a prolific writer and literary entrepreneur, owning and editing The Israelite (while married to the daughter of its publisher Edward Bloch).

The Israelite offered Mortara to its public on August 31, 1860, at the top of their list, preceding and outpricing five novels by Wise himself (two in English and three in German). For months, Wise had been teasing the first major work by this 22 year-old author.

December 24, 1858: Wise has the first scene of Mortara in hand but is withholding comment until he has seen the whole first act. Moos was then living in Louisville, KY.

December 31, 1858: WIse has seen Mortara's second scene and ventures two laconic words, "Go ahead." Meanwhile, a second poet-turned-playwright is emerging at The Israelite.

March 9, 1859: Moos, has moved on to Savannah, TN, "a small town down south and finished his drama, called MORTARA".

"The whole manuscript is in our possession". And then what? Wise offers praise of the author, "Thus much is sure, Mr. Moos combines talent with genius of a rare order."

As for the work itself, "It is full of surprising points and fine scenes. The diction is flowery, not always firm and brief enough to suit our taste, but it is chaste and pointed."

Rabbi Wise is grasping for words and we are not alone in wondering what he wants to say. "The drama will most likely be published"...will it or won't it?..."therefore we abstain at present from any lengthy criticism".

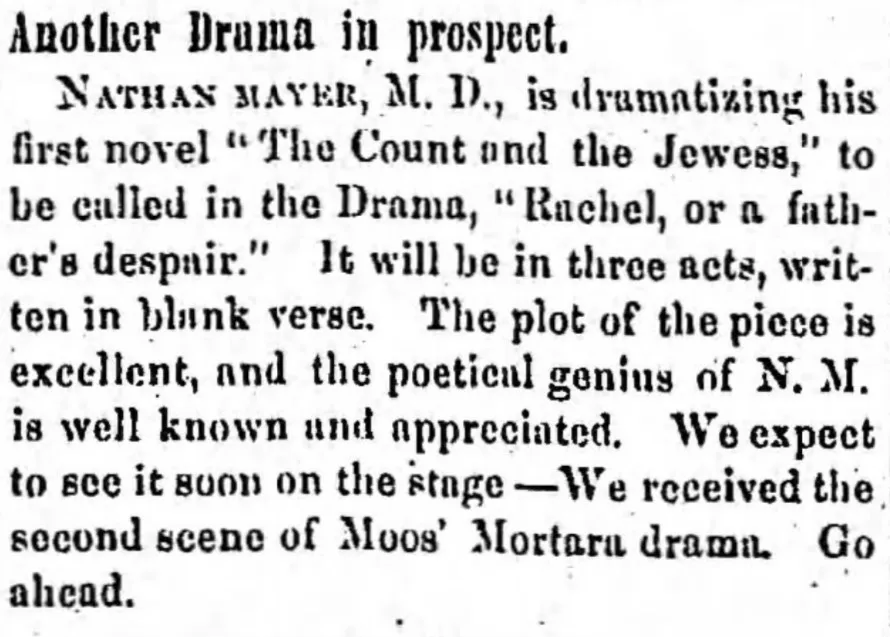

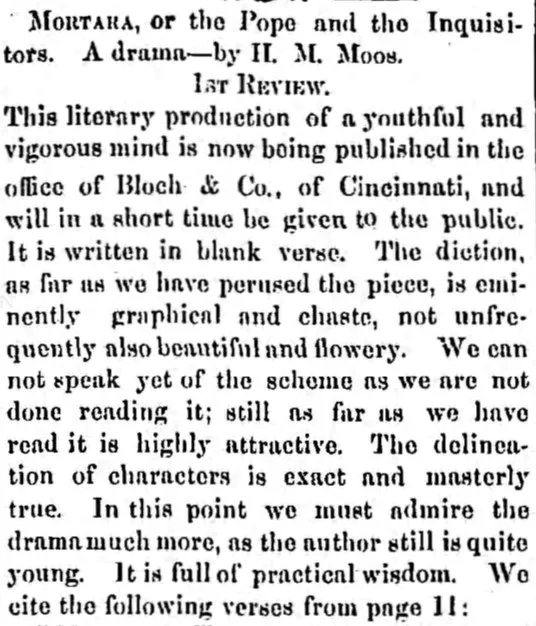

Two months later, Rabbi Wise jumps fully on board, announcing that "the literary production of a youthful and vigorous mind is now being published in the office of Bloch and Company in Cincinnati". He pulls out every imaginable flourish, although "we are not done reading it".

Wise's notice is headed "1st Review", but no further ones seem to have appeared in the pages of The Israelite. In any case, Mortara headed their weekly list for months to come.

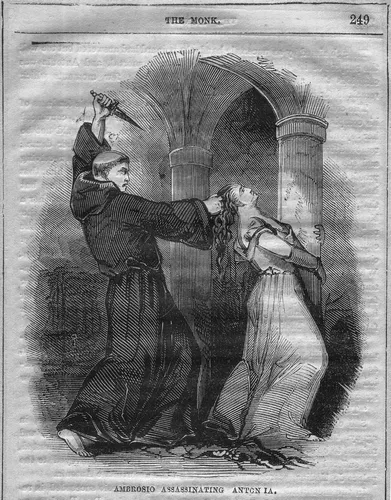

Moos' Mortara is a "Hebrew merchant of Rome" (not Bologna). His school-boy son Benjamin was baptized without their knowledge and later stolen away by the Inquisition and tortured to death (as is later Mortara himself). Revenge comes by way of Jephthah, Mortara’s nephew, who kills the Pope (Pius without a number) but is killed in turn.

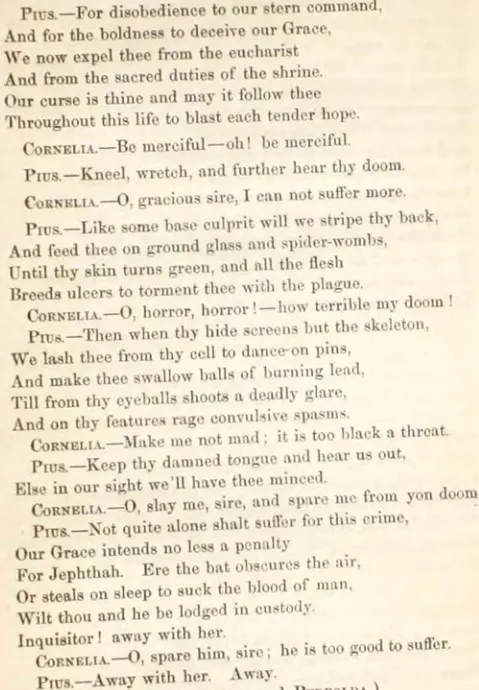

There are many characters and subplots, most notably the ill-fated romance between Cornelia (a nun) and Jephthah (nephew to Mortara and cousin to the abducted Benjamin). Pope Pius discovers the liaison and is not pleased, slamming Cornelia with some of the most distinctive language in the piece.

"Like some base culprit will we stripe thy back / and feed thee on ground glass and spider-wombs / Until thy skin turns green, and all the flesh/ Breeds ulcers to torment thee with the plague /… / Then when thy hide screens but the skeleton / We lash thee from thy cell to dance on pins / And make thee swallow balls of burning lead / Till from thy eyeballs shoots a a deadly glare / And on thy features rage convulsive spasms /… / Not quite alone shalt suffer for this crime / Our Grace intends no less a penalty / for Jephtah. Ere the bat obscures the air / Or steals on sleep to suck the blood of man / wilt thou and he be lodged in custody / Inquistor! Away with her." (H.M. Moos, Mortara, p.93)

A writer himself, Rabbi WIse had a lofty appreciation of the creative process and it must have been pleasing for him to contemplate "a young man, in a distant and lonely village, sit at the feet of the Muses and listen to Apollo's lyre" then turn to strike "the harp of Judah".

Assessing the situation more concretely, we wonder where Herman Moos found his material. How did he fix his point of view? How did a foreigner in his early twenties, navigating an acquired language in a remote corner of the South, come up with this strange and excessive but unarguably impressive work?

Herman M. Moos was born in Württemberg in 1836, then moved to America as a young man, ultimately becoming a successful lawyer in Cincinnati and a notable litterateur. By 1860, he already commanded an impressive vocabulary, a considerable literary culture and a bold imagination which he sometimes deployed with more conviction than subtlety.

What did Moos read in German? How about English revenge tragedies with Italian settings (like John Webster’s Duchess of Malfi from 1612-13 and The White Devil from 1616)? Then there were more recent novels exploiting the “gothic” horrors of that benighted Catholic realm (including Ann Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho from 1794 and Gregory Lewis’ The Monk from 1796). Moos was evidently in touch with the burgeoning popular literature of vampirism ("the bat...steals on sleep to suck the blood of man") which offered an apt metaphor for the Roman Church.

More nearly contemporary —and unequivocally American— was The Pit and the Pendulum, Edgar Allen Poe’s masterpiece of dread and despair, published in Philadelphia in 1843. While Poe focuses on the Spanish not the Roman Inquisition, Catholic inhumanity offered a cogent metaphor for inhumanity of all kinds.

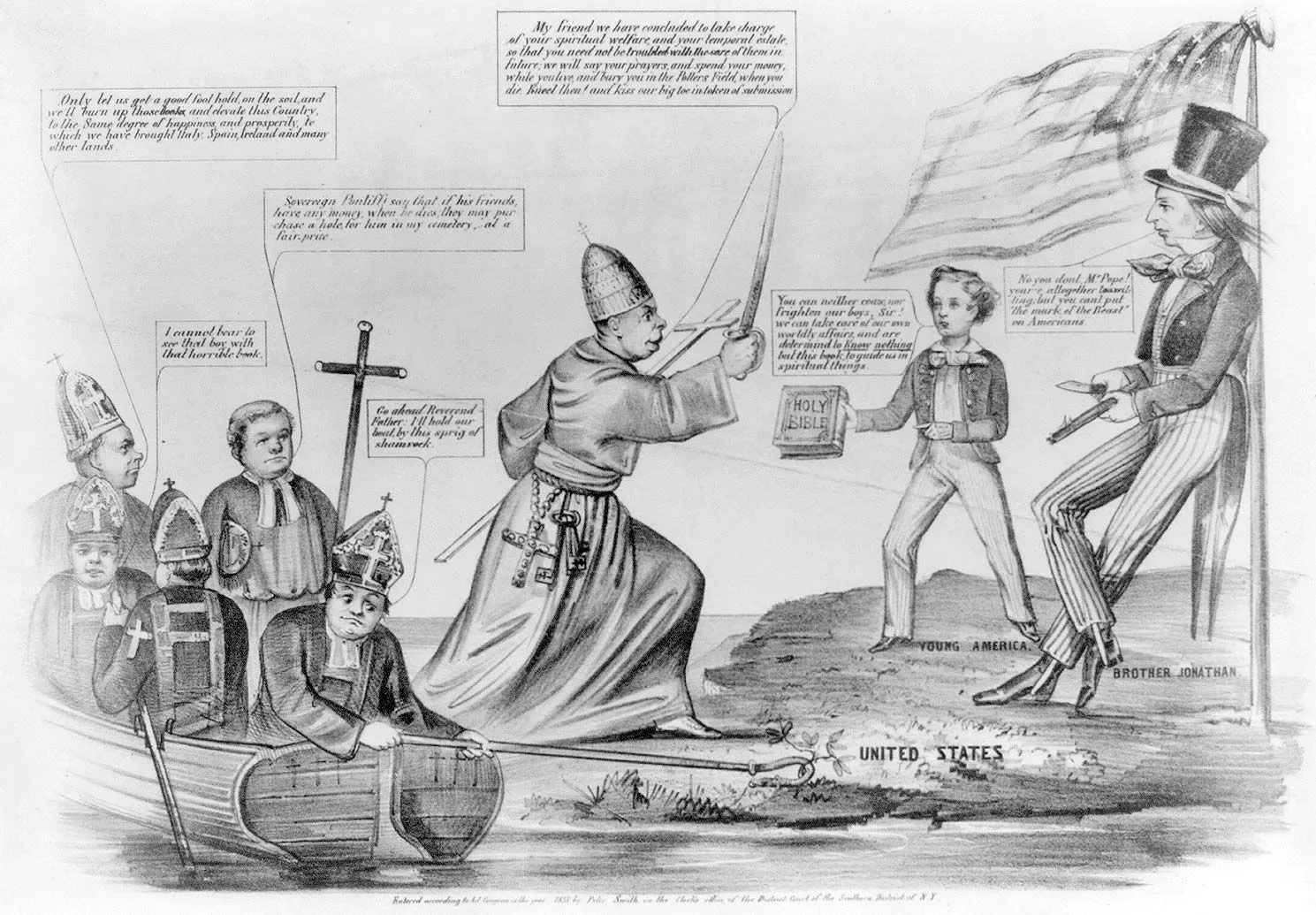

This appeared at the height of the anti-Catholic and anti-Irish mobilization of the American Nativist “Know Nothing” Party.

Reading from left to right, beginning with the figure of Pope Pius IX in the middle:

POPE: My friend we have concluded to take charge of your spiritual welfare, and your temporal estate, so that you need not be troubled with the care of them in future; we will say your prayers and spend your money, while you live, and bury you in the Potters Field, when you die. Kneel then! and kiss our big toe in token of submission.

YOUNG AMERICA: You can neither coax, nor frighten our boys, Sir! We can take care of our own worldly affairs, and are determined to "Know nothing" but this book, to guide us in spiritual things.

BROTHER JONATHAN: No you don’t, Mr. Pope! You’re altogether too willing; but you can’t put 'the mark of the Beast' on Americans.

Young America is determined to “’Know Nothing” but this book”’ while brandishing a Protestant Bible. This is an arch reference to the American Nativist Movement which dated back to the 1830s, but swung into high gear a decade later when faced by massive waves of Irish immigration. At least at the outset, they formed a secret society with members dutifully replying “I know nothing” when questioned about their organization.

How about Jewish Know Nothings? One of the most influential and extreme was Lewis Charles Levin, a founder of the American Party in 1842 (later the American Nativist Party), then representative from Pennsylvania’s First District (1845-51, the second Jew to serve in Congress). Born in Charleston, SC, in 1808 to Jewish immigrants from England, he settled in Philadelphia by 1838. A compelling orator, he began as an anti-alcohol crusader, before emerging as an anti-Catholic firebrand—quite literally. In 1844, Levin was a chief instigator of the Nativist Riots in Philadelphia which resulted in the death of over 20 Irish residents and the burning of many homes and two churches. Borne by popular acclaim, he was then sent off to Washington for six years.

Levin was not available to comment on the Mortara Affair when it broke in 1858 nor on Herman Moos’ play when it was published in 1860. (He died in the Philadelphia Hospital for the Insane in March 1860, after being committed a second time.) Still, we shouldn't be surprised if contemporary American anti-Catholicism seeped into Moos' view of the world and colored his stage writing.

Curiously enough, the Know Nothings apparently gave little thought to the "Israelites" in their midst, since there were only a few of them and they seemed a generally unmenacing lot. Their movement did not outlast the Civil War, but old-line nativists might have reacted differently a few decades later, when the ghettos of Eastern Europe began emptying onto American shores.

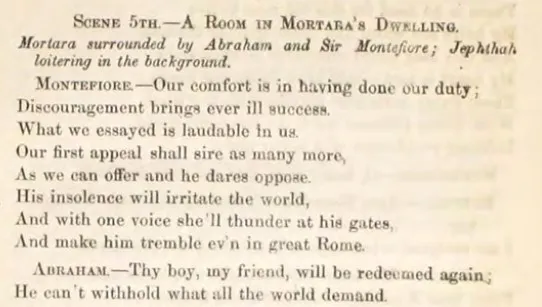

In Moos' drama, Act Three, Scene 5 unfolds in the Mortara home. Sir Moses Montefiore and Abraham (the absent Benjamin's teacher) report on their latest failed appeal to the Pope. Mortara’s ill-fated nephew Jephthah hovers on the edge of the discussion.

MONTEFIORE: His insolence will irritate the world / And with one voice she’ll thunder at his gates / And make him tremble ev’n in great Rome.

ABRAHAM: He can’t withhold what all the world demand.

Moos' point of view, expressed by Moses Montefiore, was evidently shared by many: the Catholic Church, exemplified by Pius IX, could no longer perpetrate it's age-old horrors. Modern power politics won't allow it—and maybe, just for once, Jews are on the right side of history?

Sir Moses Montefiore served as President of the Board of Deputies of British Jews from 1835 to 1874. Through much of the Nineteenth Century (he lived until the age of 101), he was arguably the world's most famous Jew and certainly the most active defender of Jewish interests on the international scene. In 1858, he traveled to Rome to intervene personally with Pius IX on behalf of Edgardo and the Mortara family—ultimately to no avail.

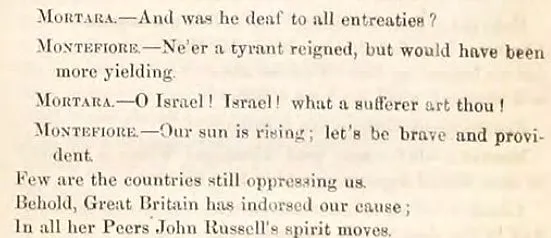

Moos portrays Mortara as a lachrymose Jew in the old style (“Oh Israel! Israel! What a sufferer are thou!”), contrasted with Montefiore, an empowered optimist looking to the future.

MONTEFIORE: Our sun is rising; let’s be brave and provident / Few are the countries still oppressing us / Behold, Great Britain has addressed our cause / In all her peers John Russell’s spirit moves.

In less benighted lands (he doesn't mention Piedmont-Sardinia), the march of Jewish progress is sure, if beset with obstacles. In 1847, Lord John Russell introduced the first version of the Jews Relief Act, allowing them to take seats in the British Parliament without swearing a Christian oath. The bill was repeatedly blocked in the House of Lords, until it finally passed on July 23, 1858—just weeks after the Mortara case broke in Rome.

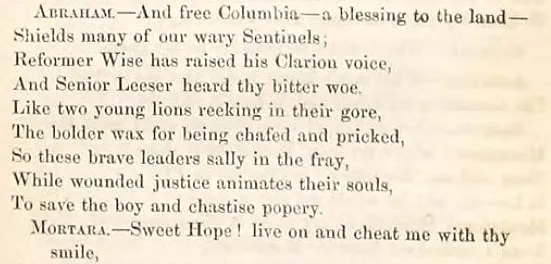

Abraham, the schoolteacher, then jumps in with a transatlantic example:

ABRAHAM: And free Columbia—a blessing to the land— /Shields many of our wary Sentinels / Reformer Wise has raised his Clarion voice / And Senior Leeser heard thy bitter woe / … / So these brave leaders sally in the fray / … / To save the boy and chastise popery.

By way of Abraham, Moos cites two American defenders of the Jewish cause: "Reformer Wise" (Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, his own personal mentor) and "Senior Leeser" (Rabbi Isaac Leeser, sixteen years older than Wise). Leeser was a defining presence on the modernizing Orthodox side, also editor of The Occident and American Jewish Advocate (an influential journal out of Philadelphia).

Cincinnati (or Louisville or Savannah) is about 5,000 milesfrom Rome or any of the other capitals that figure in the Mortara Case. How did Herman Moos keep on top of that evolving story while writing his play?

He followed the coverage in The Israelite, which reached him—slowly but surely, presumably by mail—wherever he was.

On November 19, 1858, The Israelite broke the Mortara story in explosive style (albeit five months after the knock on the door in Bologna).

On December 24, 1858 (less than six weeks later) editor Isaac Wise announced the conception of Herman Moos’ Mortara play.

In that time, the weekly newspaper evidently went from Cincinnati to Louisville, where inspiration struck. Moos then penned the first scene and dispatched it to Wise, who heralded the emerging work.

The Mortara Case signaled the emergence of American Israelites as a notable presence in international affairs. This was largely due to the activity of a few dedicated journalists who were also rabbis. Mostly German, they arrived in the New World with language skills, connections back home and an essential understanding of the European situation.

We already encountered Rabbi Julius Eckman (of The Gleaner in San Francisco), Rabbi Isaac Leeser (of The Occident and American Jewish Advocate in Philadelphia) and Rabbi Isaac Wise (of The Israelite in Cincinnati) who was ably assisted by Rabbi Max Lilienthal (who edited a weekly round-up of "Foreign Intelligence" for The Israelite).

On November 19, 1858, Isaac Wise shared a momentous ”Communication from London” to “the Hebrew Congregations this side the Atlantic”—sent by no less a personage than Sir Moses Montefiore, President of the Committee of Deputies of British Jews.

Rabbi-Editor Wise of The Israelite was evidently on an international distribution list that Rabbi-Editor Eckman of The Gleaner was not. He represented an emerging national congregation and published the journal of record for a substantial sector of American Jewry.

On October 25, 1858, Sir Moses forwarded a massive budget of news, including essential documents regarding the Jewish reaction to the Mortara Case. First there was a summary of the facts of the matter, followed by an article from The London Times (dated 9 September 1858) with the headline, “Forcible Abduction of a Jewish Child”. The Times' coverage was anchored by an appeal from the twenty-one Jewish Congregations of Piedmont-Sardinia to the British Jewish authorities, which formed a special committee (chaired by Moses Montefiore) to lobby the British government and liaise with official Jewish organizations in France and Holland. The Times also published in full the communication from the Jews of Piedmont-Sardinia (dated August 19, 1858),

Meanwhile on the same page (p.158) of The Israelite, the Reverend Doctor Lilienthal offered four cogent summaries of "Foreign Intelligence" related to the Mortara affair: “The Bologna Case”, “The Fact at Bologna”, “Rome: The Jew Boy Mortara” (focusing on French and Austrian diplomatic policy) and “France” (focusing on the official French reaction to the case).

Once the Mortara story broke, The Israelite’s coverage was incessant, detailing events in Europe but also a spirited mobilization throughout the United States. In those weekly pages, Herman Moos—not nearly as isolated as we might imagine—could gather further material for his drama, while communicating with his public and especially his chief patron Isaac Wise.

Three Dates:

March 9, 1859: In that issue of The Israelite, Rabbi Wise acknowledges a complete draft of Moos' Mortara.

June 12, 1859: The Austrian occupiers abandon Bologna, the people of the city immediately rise up and expel the Papal regime.

July 1, 1859: The Israelite announces the current upheaval in Bologna and perhaps the imminent dissolution of the State of the Church.

The leap from the streets of Bologna to a press-room in Cincinnati was remarkably swift. Indeed, this terse but fervent announcement might well represent a “Stop Press!” item.

“Hence we say, Hope On, oppressed Jews of Rome and Mr. Mortara, equal rights and civil and religious liberty will come with Victor Emanuel. The morning dawns.”

The Israelite would cover the Risorgimento selectively but steadily in the years to come, since it was an essential Jewish story with major repercussions in the international political sphere (including the decisive role of the sporadically liberal Emperor of the French).

The Italy of Moos’ Mortara, however, remained stuck in time, an age-old nightmare of oppression, cruelty and deceit—a historical fact but also a venerable literary construct.

On the contemporary stage, there were two apparent configurations of the Mortara Case: one entirely without the Risorgimento (Moos) and the other so overwhelmed with Italian patriotic fervor that Jews barely register as actual Jews.

Riccardo di Castelvecchio (in real life, the Verona-born Giulio Pullè), published his undated drama La Famiglia Ebrea (The Jewish Family) in the immediate aftermath of the annexation of the Papal Legations in 1859 (quickly followed by Tuscany, Parma and Modena), then perhaps the declaration of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861.

Unlike Moos, Castelvecchio was a fluent and prolific theatrical writer, with many well-crafted dramas to his name. His La Famiglia Ebrea—mostly set in Bologna at the time of the Mortara case—is a fast-moving detective story, featuring Rabbi Abraham Nefeg, an apostle of liberty who didn't let Jewish belief or custom cramp his style.

In 1830, twenty-nine years before the main action in 1859, Nefeg’s son Beniamino was baptized by a servant girl, then seized by the Papal Commissioner. The Rabbi, however, was forced to flee since he was a confederate of the insurrectionist Ciro Menotti (hanged in Modena in 1831). After wandering the world for three decades, Nefeg returned home to track down his son.

Revelations fall into place… Beniamino is now Gregorio, the secretly Church-hating (but still vaguely Christian) secretary to the Papal Commissioner (the same one who oversaw his abduction many years before). There is even a love interest for Beniamino / Gregorio, a girl who was sequestered by the Church at the same time as him, but evidently Christian from the start.

Meanwhile, patriotic hordes surge noisily offstage, then rise up and overthrow the Papal regime—leaving Nefeg in command.

Nefeg dismisses the deposed Commissioner with a nice mix of generosity and contempt—anchored by an apt Old Testament allusion:

PAPAL COMMISSIONER: Am I allowed to leave?

RABBI NEFEG: Go! Go, by all means! Announce tothe satraps of your Babylon how once upon a time a fiery hand wrote this on the wall at Belshazzar’s Feast, “God has taken the measure of your kingdom. He has weighed you in the balance and found you wanting. Your kingdom will be torn asunder and your scepter shattered.”

The Commissioner reaches for a last niggling victory:

PAPAL COMMISSIONER: You, however, will never gather the fruit of your triumph! I leave your family sunk in discord—with a Jewish father and a Christian son!

But Nefeg cheats him of even that:

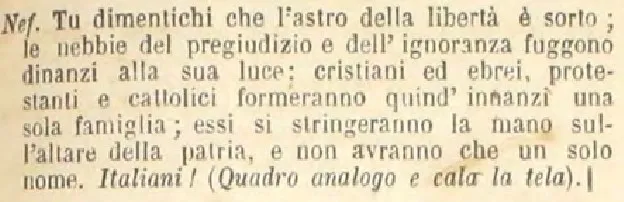

RABBI NEFEG: The star of liberty has risen! That is what you forget! The fog of prejudice and ignorance are fleeing before liberty’s light. Christians and Jews, Protestants and Catholics, are destined to form a single family. They will all shake hands on the altar of the homeland and they will have but a single name, ITALIANS!

(The curtain comes down on a "quadro analogo".)

The "quadro analogo" ("blocked scene") would have been a final tableau, with the actors frozen in place while the audience cheered uproariously. Riccardo di Castelvecchio was a well-known and highly bankable playwright, so it is easy to imagine La Famiglia Ebrea bringing down the house, especially in newly liberated towns in the rapidly shrinking Papal State.

(11) MORE PAPAL FALLIBILITY

On 1 May 1861, Vittorio Emanuele II made his first royal entry into the city of Bologna. This came barely four years after Pius IX’s less enthusiastic welcome (on 10 June 1857), three years after the Pope’s sequester of the Mortara child (on 23 June 1858) and two years after the expungement of his local regime (on 12 June 1859).

In those fast-moving times, the liberation of Bologna from Papal rule might already have seemed an old story. The King of Piedmont-Sardinia had been squaring away Italian territory at a breath-taking pace: Lombardy (June 1859); Bologna and the Legations (June 1859); Tuscany, Parma and Modena (March 1860); the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (October 1860).

On 17 March 1861, after a flurry of parliamentary due process, Vittorio Emanuele proclaimed himself King of a more-or-less United Italy. By the time of his arrival in Bologna on 1 May, all that remained on the wrong side of the map was Austrian Venice and Papal Rome.

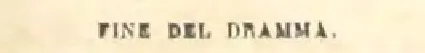

This "due process" is intriguing in its own right . The Deputies assembled in a new and enlarged temporary hall in Palazzo Carignano, built to accommodate more and more delegates from recently incorporated territories—temporary because no one knew how much longer the "national" legislature would continue to meet in Turin, the old Piedmontese capital. (In fact, the seat of government shifted to Florence in 1865 and finally Rome in 1871.)

Among those making history were four Jewish deputies: Giuseppe Finzi, David Levi, Tullo Massarani and Guido Susani. Many more Jewish Deputati and Senatori would serve in the years to come—until the Fascist Racial Laws ended all that in 1938.

Giuseppe Finzi (1815-86) from Mantua. His front-line activism began in his student days, including a stint in an Austrian prison, before he emerged as an influential Italian statesman.

David Levi (1816-98), a native Piedmontese, also got an early start in his long career as patriot, writer and political theorist, spending years in revolutionary circles in Switzerland and Britain.

Tullo Massarani (1826-1905), from an old and distinguished family in Mantua, studied painting before making a name for himself in literature and public service.

Guido Susani (1823-92), born in Mantua but raised in Milan, had a long and distinguished career in engineering and entomology, but a more problematic one in politics, being implicated in a bribery scheme linked to railroad construction.

On the postcard, Prime Minister Camillo Cavour is shown in small scale in a long view, slogging through the everyday work of unification—oddly enough, since Italian image-makers usually favored bold displays of protagonismo, with dauntless heroes redirecting the course of history.

In this rendering, a diaphanous Italia floats to earth in the new but temporary premises of the Chamber of Deputies, while Camillo Cavour gestures to the documents in the case—presumably including his own speeches, now transcribed in the parliamentary records. Are we supposed see this spectral agent as sharing a portentous secret? Before another ten weeks were out, the Prime Minister would be dead, while the Italy he labored to realize lived on.

In Italy, myth-making of this sort was nothing new. Still, the alternate view of Cavour— receding through the small end of the telescope—brings us nearer than most to the real events.

In the Subalpine Parliament, the Prime Minister realized a revolutionary agenda without raising his voice or seeming to take sides. He offered the King authoritative advice on almost everything, while revealing few ambitions of his own. Before Italy even existed, he represented that country in diplomatic affairs, working quietly behind the scenes.

The transcripts of the legislature in Turin make for riveting reading. We can track these history makers on the ground, hearing their words in real time.

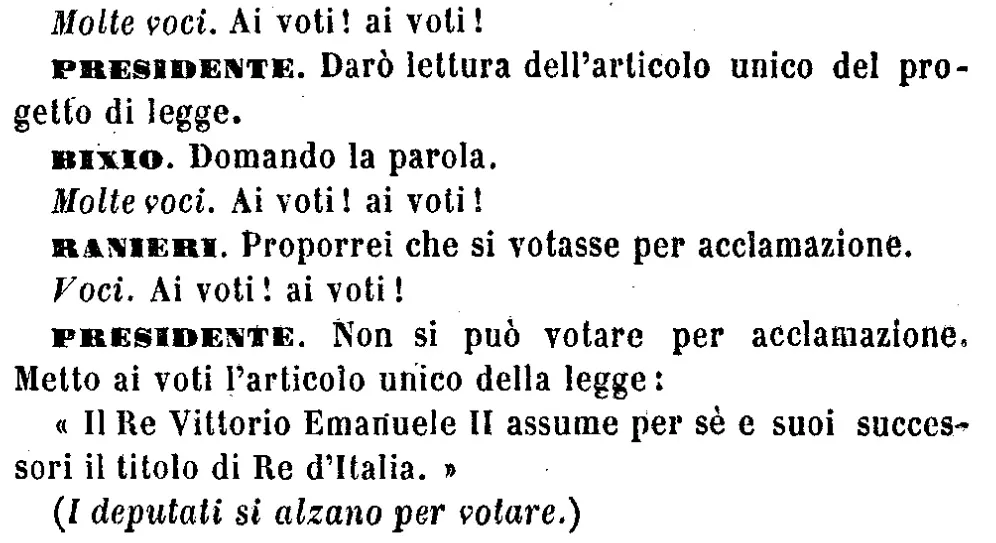

DISCUSSION OF THE LEGISLATIVE PROGRAM TO PROCLAIM VITTORIO EMANUELE II AS KING OF ITALY.

PRESIDING OFFICER [Ugo Rattazzi]: Our agenda focuses on a legal framework for Vittorio Emanuele II assuming the title of King of Italy.

Since notice of this proposed legislation is being communicated to the honorable deputies somewhat late, many might not have had the chance to read it. So, it seems appropriate for the bill's sponsor to share it with this Chamber.

MANY VOICES: Let's vote! Let's vote!

PRESIDING OFFICER: I will read the single article of this legislative proposal.

[DEPUTY GIROLAMO] BIXIO: I claim the floor.

MANY VOICES: Let's vote! Let's vote!

[DEPUTY ANTONIO] RANIERI: I would propose that we vote by acclamation.

VOICES: Let's vote! Let's vote!

PRESIDING OFFICER: We cannot vote by acclamation. I will put the single article of this law to the vote: "King Vittorio Emanuele II assumes for himself and his successors the title of King of Italy."

(The deputies rise to vote.)

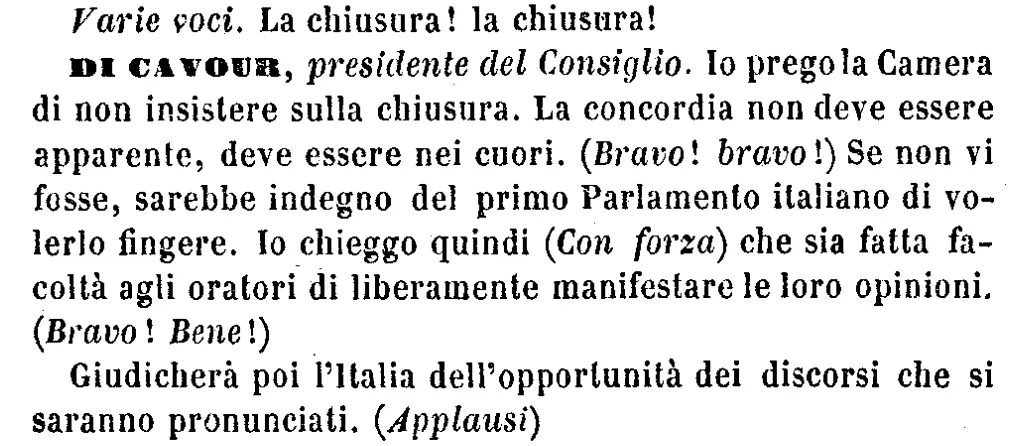

VARIOUS VOICES: To cloture! to cloture!

[Conte Camillo Benso] DI CAVOUR, President of the Council [of Ministers]: I would ask that the members of this chamber not insist on cloture. Their agreement must not only be apparent, it must be registered in their very hearts. (Bravo! Bravo!)

Such agreement would be unworthy of the first Italian Parliament if it were merely simulated. I therefore ask (speaking forcefully) that commentators be given full faculty to voice their opinions. (Bravo! Good!)

Italy will then judge the appropriateness of these arguments. (Applause.)

So, discussion takes place. Opinions are recorded. And then...

PRESIDING OFFICER: I now read this single article and put it to a vote: "King Vittorio Emanuele II assumes for himself and his successors the title of King of Italy".

(The Chamber expresses unanimous approval. There is prolonged applause from the ranks of deputies and from the galleries, with cries of "Long Live the King of Italy!")

(General applause and fervent cries of of "Evviva!")

Now we proceed to the roll call.

Since many of the deputies are voting for the first time, I should specify that dropping a white ball in the white urn indicates a favorable vote and dropping a black ball in that same white urn indicates a vote to the contrary. The black urn is for the remaining ball which the deputy does not use.

(The roll call then ensues.)

Ugo Rattazzi, the presiding officer, did well to clarify voting procedures for novice legislators from newly enfranchised territories. But even so...

PRESIDING OFFICER: Before publishing the outcome of the vote, I must note that two deputies have reported errors in casting their votes. One placed the black ball in the white urn and the white ball in the black urn, while meaning to cast a favorable vote. The other placed the black ball in the white urn rather than in the other urn.

With these considerations in mind, I publish the outcome of the vote.

(Profound Silence.)

PRESENT AND VOTING: 294

MAJORITY: 148

VOTES IN FAVOR: 292

OTHERS CAST AS I INDICATED: 2

This Chamber then expresses unanimous approval.

(Double salvo of applause and cries of "Long Live the King of Italy!")

Barely two weeks later came another parliamentary debate and another momentous proclamation. This time, however, consensus was less easy to achieve.

Inevitably, the Roman Question had come to the fore. Could anyone truly imagine a United Italy without the Eternal City as its capital?

But what about the Pope—especially an intractable one like Pius IX? And what about Catholic political factions at home and abroad?

The deputies wrangled for three days (25-27 March 1861). Starting with the Middle Ages, they reprised Papal rights and prerogatives like an academic case of law. Meanwhile, they kept a nervous eye on the eventual reaction of foreign powers. Emperor Louis Napoléon was then struggling with Catholic reactionaries in France, while keeping troops on the ground to shore up the Roman regime—but with less and less conviction.

Even the most committed patriots stopped short of stating the obvious, on the floor of the Turin Parliament at least. There was simply no room on the same peninsula for both a modern Italy and a retrograde State of the Church.

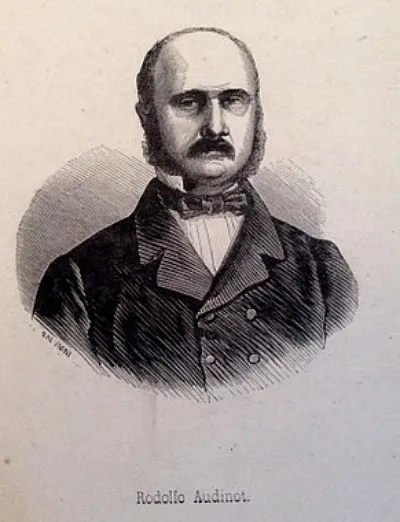

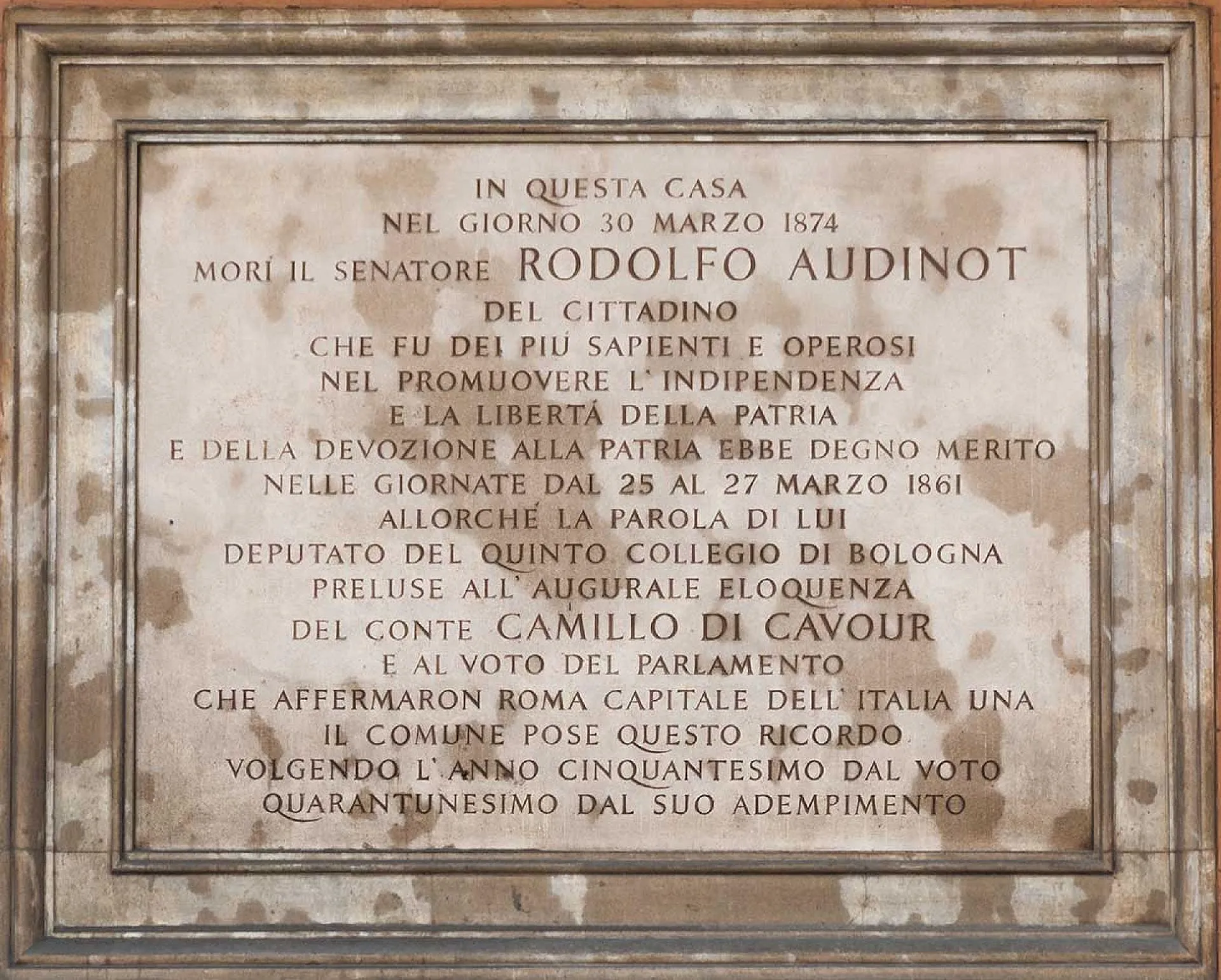

Someone needed to kick that issue out into the open and the man was Rodolfo Audinot, deputy from the former Papal territory of Bologna. Audinot was an unflinching liberal, experienced in working with, around and against the Roman regime.

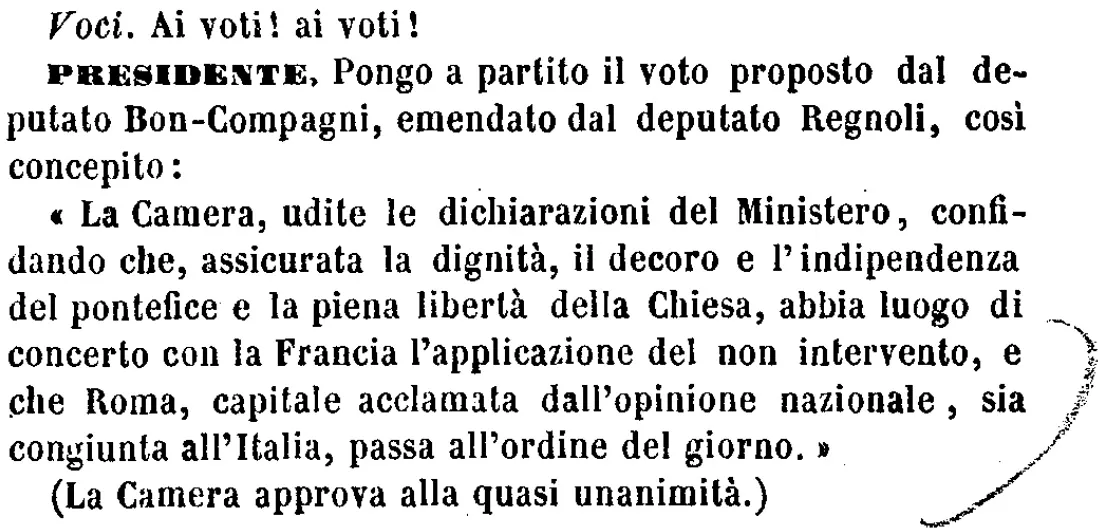

[AUDINOT]: "The present agenda is based on two explicit premises: First, Rome is capital of this United Italy. Second, temporal and spiritual powers must be kept separate. Since these matters lie within the competence of this Parliament, we see a clearly marked path forward."

[AUDINOT]: "We, my dear sirs, are attempting the greatest project ever given to man—harmonizing Church and State by way of liberty."

[AUDINOT]: "In the name of national sovereignty, we ask the Pontiff to set aside his temporal power. We then offer the Church complete liberty, guaranteeing the independence and inviolability of its spiritual power."

This was heady stuff but simple and clear, exactly what most deputies wanted to hear.

VOICES: Let's vote! Let's vote!

PRESIDING OFFICER [Ugo Rattazzi]: I am now putting to the vote the proposal by Deputy [Carlo] Bon-Compagni as emended by Deputy [Oreste] Regnoli, in these terms:

"This Chamber has heard the statements by the Minister [Cavour] regarding the union of Rome with Italy, hailed by national opinion as its Capital. This will be considered a matter of policy if the dignity, decorum and independence of the Pope can be guaranteed along with the complete freedom of the Church, while assuming France's non-intervention."

(The Chamber approves this almost unanimously.)

“RODOLFO AUDINOT…AS A CITIZEN WAS AMONG THE MOST CAPABLE AND ACTIVE IN PROMOTING THE INDEPENDENCE AND LIBERTY OF THE FATHERLAND. HIS DEVOTION FOUND ITS REWARD ON THE DAYS OF 25 TO 27 MARCH 1861, WHEN HIS WORDS AS DEPUTY IN THE PARLIAMENT…OFFERED A PRELUDE TO THE AUSPICIOUS ELOQUENCE OF COUNT CAMILLO DI CAVOUR AND THEN THE VOTE AFFIRMING ROME AS THE CAPITAL OF UNITED ITALY…”

That was Audinot's finest hour and he went down in history as the man who did the deal—although Roma Capitale remained only a national aspiration for another nine years. Meanwhile, his fellow Bolognese would never forget that one of their own slammed the final door on centuries of Papal oppression.

The 27 March decree came by acclamation, with no proper vote and no clear tally. Uppermost in every mind was the vexing question of French neutrality. Napoleon III's troops had been patrolling the Papal Capital since 1850 and Pius IX couldn't last long without them.

"Hunting Season Begins in Rome / The French Guardsman, 'Away with the bandits! There's no hunting in the territory of the Holy Father.' The Englishman loading the rifle, 'Let Vittorio get in a good shot and we'll be more than pleased:'" .

The popular illustrator and cartoonist Adolfo Matarelli captured a wild moment in European political history—open season on Pius IX and the Roman Church more generally. Liberals and anticlericals (including Matarelli himself) were relishing every twist and turn in the story.

Did the two supercilious Englishmen on the far left represent individuals or merely national types? The shooter in the straw hat is presumably King Vittorio Emanuele II (cast as a generic poacher). The red-shirted figure in the semi-conical hat is Giuseppe Garibaldi and the French gendarme is Louis Napoléon. At the lower right, huddling with Pope Pius IX (in white, with a skull-cap), we see Francesco II deposed King of the Two Sicilies (then living as an exile in Rome, here dressed as a comedic Neapolitan pazzariello). Meanwhile, the monsters of clerical unreason perform aerial acrobatics within easy shot.

Pius IX was immutably fixed in his own reality. "Non possumus!"—"We cannot" (alternately, "It is not possible for us!"—in old-fashioned Latin, was his charcteristic reply when faced wtih change of almost any kind. This earned him the derisive nickname of "Pio, no, no!" with a double negative, playing on "Pius the Ninth = Pio Nono" in Italian.

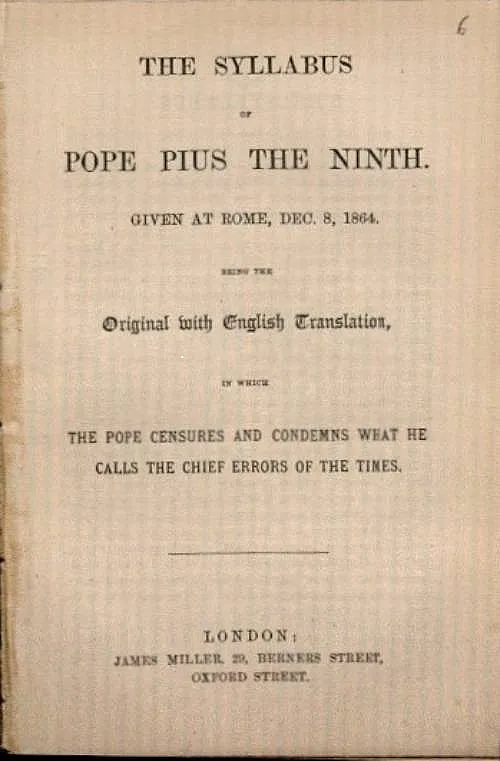

On 8 December 1864, Pius IX promulgated his ideological masterwork, the Syllabus of Errors, outlining the pernicious beliefs that bedeviled the world of his day.

There were eighty "errors" in his handy checklist, retrieved from the Pope's own encyclicals. The last pronouncement encapsulated all the rest: "The Roman Pontiff can and ought to reconcile and harmonise himself with progress, with liberalism and with modern civilisation." The reply was an emphatic "NO POSSUMUS!"

The beleaguered Pope called in reinforcements, convening a great council in the Vatican in 1869—the first universal gathering of Church hierarchs in three centuries. Their mandate was to stop the course of history (or at least, give their reactionary agenda an ideological form that would outlast its real-world viability).

The Council sat from December 1869 to September 1870. Their crowning achievement was the Doctrine of Papal Infallibility, to wit: The Pope is protected from error by the Holy Spirit when he pronounces ex cathedra ("speaking from the throne") on matters of faith and morals.

So, "No Possumus" for the ages... Meanwhile, Pius IX couldn't resist gifting his enemies the ammunition they craved.

In 1864, a nine year-old apprentice shoemaker from the Roman Ghetto named Giuseppe Coen was whisked away to the House of the Catechumens (willing or not, according to various accounts). "For the Jews and the enemies of the Church's temporal power, this had all the making of Mortara redux". (Kerzer, p.258).

The Coen Case dragged on. The State of the Church had already been reduced to the city of Rome and its immediate region, which the Pope held only by means of a French occupying force. Emperor Napoleon III was outraged at this latest enormity and the Coen family immediately appealed to his ambassador in that city.

Then "just a few weeks after the ambassador's request for Giuseppe's restitution was denied, the French signed an agreement with the Italian government to begin removing all French troops from Rome...A few years later, when the paltry papal guard was finally overrun by Italian troops, the Austrian ambassador to Rome, referring to Giuseppe Coen, told his sovereign, Franz Josef: 'Italy should be erecting arches of triumph in honor of this little Jew.'" (Kertzer, p.259)

Whatever his beliefs, Louis Napoléon was soon locked in a hopeless war with the King of Prussia and had no troops to spare. By 19 July 1870, Paris was under siege and on 2 September, the Emperor himself was taken prisoner at the catastrophic Battle of Sedan.

On 20 September 1870, the Italian army entered the Eternal city through a breach in the old defensive walls and Roma Capitale became a geopolitical fact. On that very day, the Vatican Council folded due to force majeur and Pius IX began an essential rebranding—shifting from Infallible Pope to Prisoner of the Vatican.

One of the most riveting scenes in the film Rapito / Kidnapped focuses on the events of 20 September 1870.

Riccardo Mortara, Edgardo’s oldest brother, is a Lieutenant in the liberating army. Fresh from battle, he bursts into a Roman seminary to rescue his sibling…now that everything has changed.

Or has it? The catechizers succeeded brilliantly in reprogramming Edgardo as an extreme convert. He screams abuse at his brother, accusing him of every crime against man and God.

What actually happened, then and there? We know only that Lieutenant Mortara took part in the Liberation. Meanwhile, their father Momolo Mortara rushed to Rome with a drama of that sort in mind.

In psychological terms at least, the cinematic reconstruction is sadly convincing, based on the later history of the Mortara family. We can also recall the last act of Riccardo di Castelvecchio’s drama, La Famiglia Ebrea / The Jewish Family.

PAPAL COMMISSIONER: You, however, will never gather the fruit of your triumph! I leave your family sunk in discord—with a Jewish father and a Christian son!

RABBI NEFEG: The star of liberty has risen! That is what you forget! The fog of prejudice and ignorance are fleeing before liberty’s light. Christians and Jews, Protestants and Catholics, are destined to form a single family. They will all shake hands on the altar of the homeland and they will have but a single name, ITALIANS!

%20and%20Brother.webp)

History is never that simple, needless to say, nor are the vagaries of human emotion. But what did the Star of Liberty and the Altar of the Homeland really signify in the first generation of Jewish Emancipation?

Riccardo (possibly the clean-shaven man on the left) evidently embraced the vision of a modern Italy while expressing impatience with the habits and customs of his Jewish past.

Marianna (seated in the middle) was emotionally broken by “The Mortara Case” and suffered nervous crises for the rest of her life. Still, she never relinquished the maternal tie to her apostate son.

As for Father Pio Maria Mortara, formerly Edgardo…God only knows! In the historical records, we see him as intellectually brilliant but strangely intense and more than a little obsessive at times. Was he ever comfortable in his own skin?

He traveled widely as a missionary, preached in many languages and launched unsuccessful schemes to convert Jews (most notably in the United States of America). In 1940, he died in a Belgian monastery at the age of 89, just two months before the Wehrmacht moved in.

NOTE:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.