GARIBALDI & GOLDBERG LAND IN SICILY: A Jewish View of the Italian Risorgimento (Part 5)

CONTENTS:

(12) VA PENSIERO and VIVA V.E.R.D.I.

(13) WHAT'S IN A NAME ("Goldberg", for example)?

(12) VA PENSIERO and VIVA V.E.R.D.I.

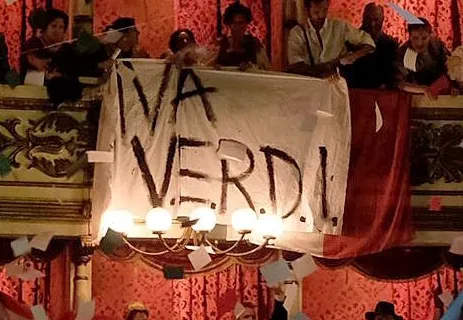

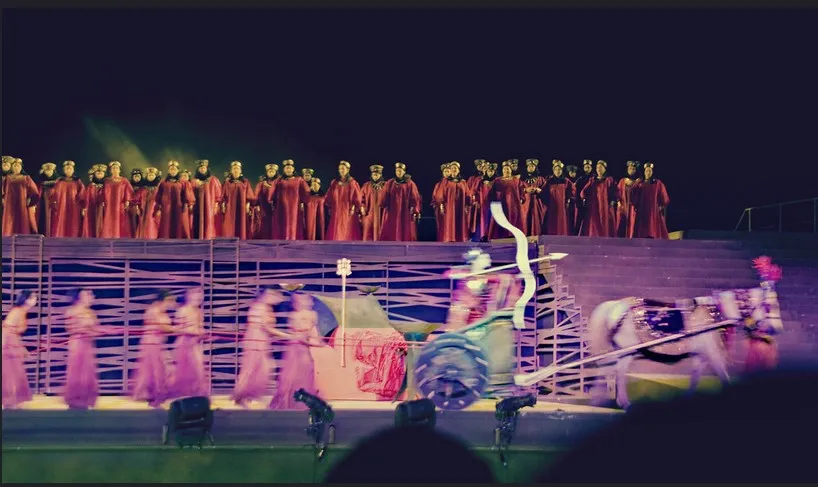

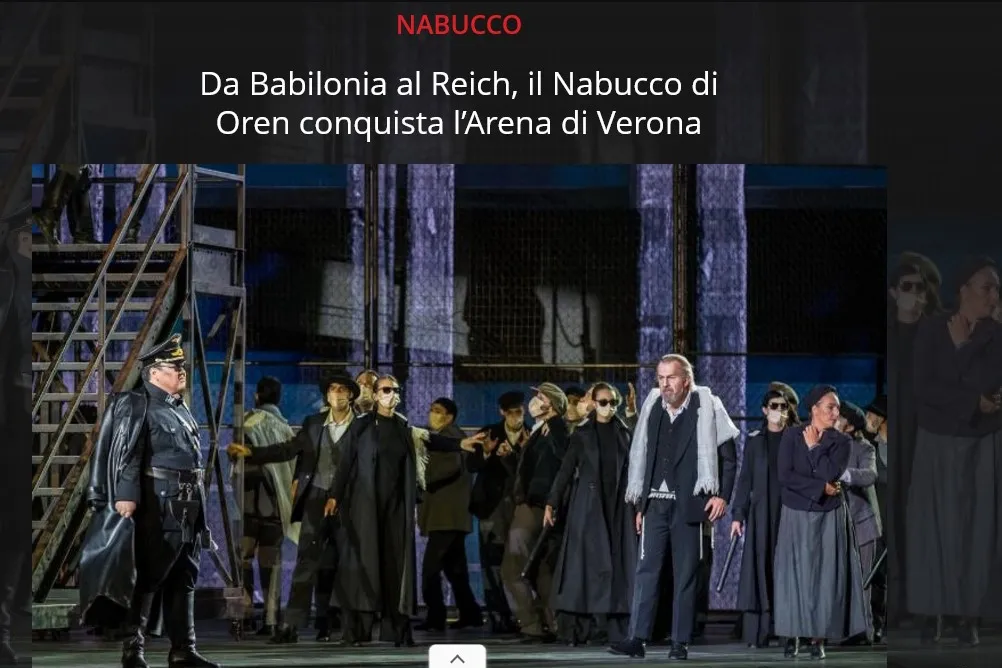

Metaphor-mixing is the name of the game in Nabucco productions these days —but Verona 2017 took the cake, pulled out all the stops and went over the top.

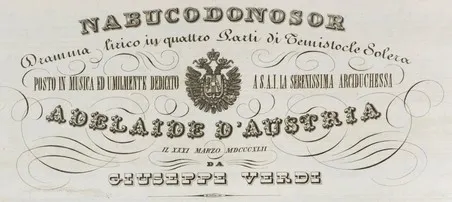

Working the old play-within-a-play thing, we watch Giuseppe Verdi's Hebreo-Babylonian drama take shape at its own 9 March 1842 première at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan.

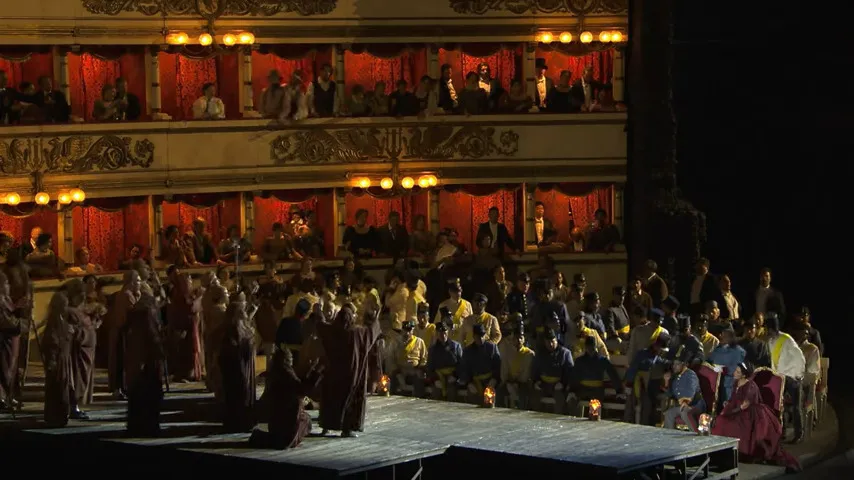

In Act One and Act Two, the simulated exterior of that fabled opera house did duty first as the Temple in Jerusalem and then the Royal Palace in Babylon —all in the midst of Verona's no less fabled Roman amphitheater.

Then the structure rotated to reveal an uncanny replica of La Scala's gilded interior, with a restless Milanese audience in its seats and the opera Nabucco on its stage.

So, we have Sixth Century BC (Jews in Babylon), First Century AD (Romans in Verona) and Nineteenth Century AD (Italians in Milan) —all at once, here and now.

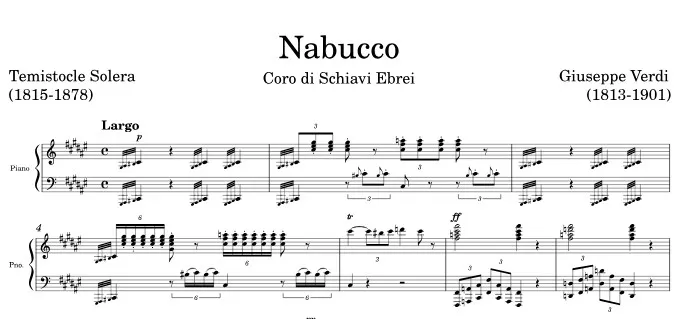

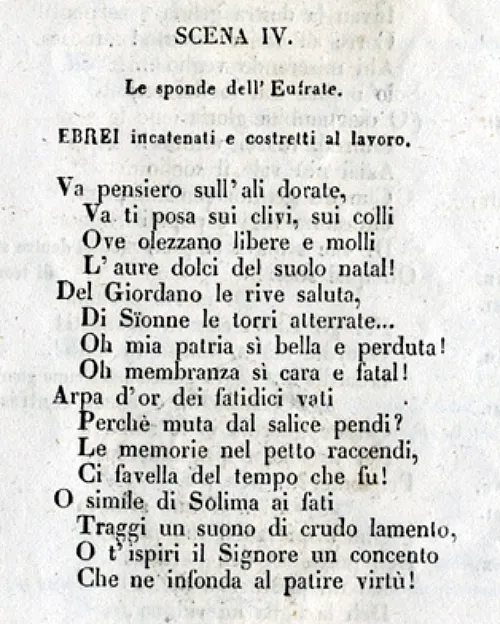

Va Pensiero, the chorus of exiled Hebrews lamenting their lost homeland, is the centerpiece of every staging.

Fly, my thoughts, on wings of gold; go settle upon the slopes and the hills, where, soft and mild, the sweet airs of my native land smell fragrant!

Greet the banks of the Jordan and Zion's toppled towers. Oh, my homeland, so lovely and so lost! Oh memory, so dear and so dead!

Golden harp of the prophets of old, why do you now hang silent upon the willow? Rekindle the memories in our hearts, and speak of times gone by!

Mindful of the fate of Solomon's temple, Let me cry out with sad lamentation, or else may the Lord strengthen me to bear these sufferings!

(Translation from BBCmusic Magazine)

Truth be told, Nabucco can be heavy going at times, with its Ancient Middle Eastern setting, massed choruses, sententious arias and pounding brass. But Va Pensiero — The Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves —is delightfully cantabile and sometimes cast as a jolly sing-along.

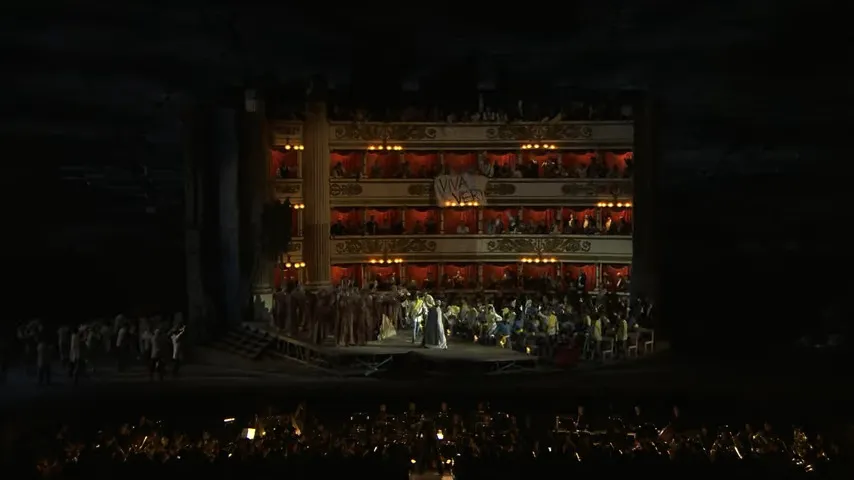

The VIVA V.E.R.D.I. meme was launched at La Scala on the evening of 9 March 1842 ...or so the story goes. On that gala occasion, the lamentation of the Jewish exiles — especially the heart-stopping line "O, mia patria si bella e perduta!" (Oh, my homeland, so lovely and so lost!) — stirred the audience.

Nascent patriotic sentiment erupted in cheers of "Viva Verdi" (the composer Giuseppe) and / or "Viva V.E.R.D.I.", (VITTORIO EMANUELE RÈ D'ITALIA = Victor Emanuel King of Italy). These barely coded calls for national liberation temporarily shut down the performance ...or something of the sort (with or without enormous tricolor flags).

It is always a pity to wreck a great story, especially one that wrote itself so nicely after the fact. Something did indeed happen in Milan at the Teatro alla Scala on the evening of 9 March 1842— but ...it would seem... only remotely that.

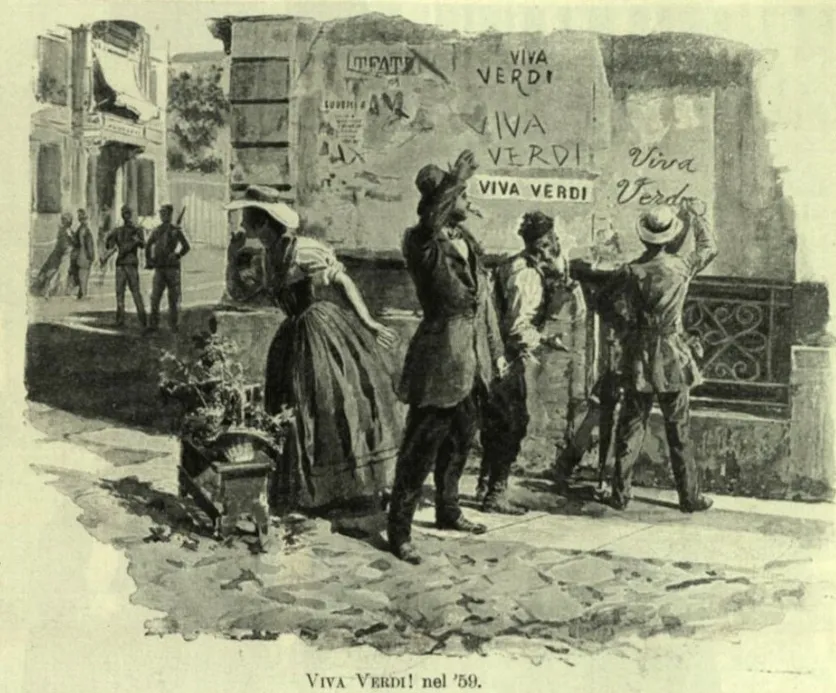

In the magazine illustration, a charming rustic flower-seller keeps her eye on the Austrian militia, patrolling the Lombard capital for maybe the last time. Meanwhile, her accomplices do their bit for the nationalist cause.

Viva V.E.R.D.I. was certainly in full spate in Milan by 1859 and in other soon-to-be-redeemed Italian territories as well. When Vittorio Emanuele II entered the city on 8 June of that year, he would have seen the slogan —with theme and variations — everywhere he looked.

This nostalgic image was published less than a week after the composer's death on 27 January 1901. Exactly a month later on 27 February, an estimated 300,000 lined the streets of Milan for his funeral procession —raising a heart-stopping chorus of Va Pensiero as the hearse passed.

Few of those 1901 mourners were likely to quibble with the Va Pensiero story, lovingly crafted over sixty years. But what about that anthem —in real time —on 9 March 1842?

In 1842, Giuseppe Verdi was only 28 years old and not the grandiose figure he later became. The public knew him only for one modest success (Oberto, Conte di San Bonifacio, 1839) and a single-performance flop (Un giorno di regno, 1840), both produced at La Scala.

Vittorio Emanuele was at the beginning of his career as well. The 21 year-old Duke of Savoy and hopeful Crown Prince of Sardinia, was engaged to marry his first cousin Maria Adelheid von Habsburg, Archduchess of Austria and daughter of the Viceroy of Lombardy-Venetia (local oppressor-in-chief, that is to say).

On 9 March 1842, the Italian national project was still at a primordial stage (it is easy to forget how quickly those pieces eventually tumbled into place) and Vittorio Emanuele was not yet king of anything, even Sardinia. That happened on 24 March 1849, after the abdication of his father Carlo Alberto.

In Milan at least, Maria Adelheid was probably better known than her soon-to-be-husband. She had been born right there in the royal palace, enjoying regal honors. And she— not he— could claim a personal connection to Nabucodonosor (as it was then known).

The Archduchess of Austria, affianced bride of Vittorio Emanuele, graciously honored the opera with her patronage —Va Pensiero and all the rest.

What actually happened on 9 March 1842 at the première of Nabucodonosor / Nabucco? Judging from the scant evidence, there was evidently an "incident" —a breach of protocol of some kind.

One grand choral piece roused the audience, eliciting insistent cries for more — bringing the performance to a temporary halt. Disruptions of that sort were discouraged at La Scala (perhaps strictly forbidden, if a 1797 regulation was still in effect).

However, that grand choral piece was Immenso Jehova in Act Four, not Va Pensiero in Act Three.

Immenso Jehova was effectively the conclusion of the opera, a far more coherent moment for an explosive demonstration —marking the dramatic redemption of the Jewish people through divine intervention.

Va Pensiero —by comparison —was a heart-rending lament, not a rousing call to victory.

What to do about Va Pensiero? You couldn’t let it slide with a mere encore— audience expectations being what they are.

In the inimitable Italian style, the organizers of Verona 2017 opted for "il minimo indispensabile" (the least you can get away with).

The fake audience on stage (not the paying customers in the Arena) promptly called for an encore which was granted (with no sing-along). Then a solitary banner was unfurled from one of the boxes. Then the La Scala interior set rotated out of sight with startling speed.

The massive “Viva Verdi / V.E.R.D.I.” spectacle was staved off until the end of the performance (after Immenso Jehova), with minimal harm to the artistic integrity of the play.

What actually happened on the evening of 9 March 1842— without back-filling as yet unwritten history?

Maybe there was a surge of nascent Italophilia in the house...? Maybe the first-night public was celebrating a promising young composer (Giuseppe Verdi), happily back on track after his Un giorno di regno fiasco...?

In any case, 9 March 1842 need not have been a rousing anti-Austrian occasion nor the young Vittorio Emanuele the man of that political moment (as yet).

Looking at the facts, we know that Nabucco was performed some seventy times at La Scala before the year was out.

Meanwhile, Giuseppe Verdi promptly sent his grand epic to Austrian-ruled Venice (1842), the Habsburg city of Trieste (1843) and Vienna, the Imperial Capital (1843).

It was a huge success in all those places— with no distracting politics, it would seem.

Meanwhile there is the Jewish theme, which remains essential to Temistocle Solera's libretto, however much producers heap the Risorgimento trappings.

In Summary:

ACT I: Nebuchadnezzar II, King of Babylon (here Nabucco) conquers Jerusalem and lays waste to the Temple. He then enslaves the Jews (including Zaccaria, the High Priest) and exiles them to Babylon. Nabucco’s two daughters Fenena and Abigaille fall in love with Ismaele, nephew of the Israelite king.

ACT II: Nabucco heads off to war, leaving Fenena to rule in his absence. Abigaille then discovers that she is not actually Nabucco’s daughter but the offspring of slaves, so she plots to seize power in her own right.

ACT III: Abigaille achieves her goal, then orders the execution of the Jews. Nabucco returns to Babylon, is duped into signing their death warrant and then goes mad. (Here, "Va Pensiero".)

ACT IV: Nabucco, now imprisoned, sees the Jews led off to their death. He invokes the Jewish God, begs for forgiveness and vows to convert. Through divine redemption, the Israelites are liberated while Nabucco regains both his kingdom and his sanity. (Here, "Immenso Jehova".)

Solera didn't invent this wildly improbable storyline on his own. Instead, he mashed up various ancient sources, mostly apocryphal, known to biblical scholars of his time.

For Va Pensiero, he channeled the 137th Psalm (harp hung on the willow and all):

By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion.

Upon the willows in the midst thereof we hanged up our harps.

For there they that led us captive asked of us words of song, and our tormentors asked of us mirth:

'Sing us one of the songs of Zion.

How shall we sing the LORD'S song in a foreign land?

If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning.

Let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth, if I remember thee not;

If I set not Jerusalem above my chiefest joy.

Remember, O LORD, against the children of Edom the day of Jerusalem;

Who said: 'Rase it, rase it, even to the foundation thereof.'

O daughter of Babylon, that art to be destroyed;

Happy shall he be, that repayeth thee as thou hast served us

Happy shall he be, that taketh and dasheth thy little ones against the rock.

(Mechon-Mamre Translation)

Verdi's opera probably marked the deepest penetration of perceived Jewishness in the culture of Risorgimento Italy, with the old tropes of exile and oppression set to stirring music. Meanwhile —as we have seen— many real-life Jews were ready to leave the tears behind and play decisive roles in an emerging nation state.

However resonant the Nabucco story in Nineteenth Century Italy, it remained a historical spectacle rooted in the ancient Middle East. While Verona's 1958 edition might have emerged from Cinecittà in Rome, no one thought to question the old concept.

It was harder to achieve Babylonian grandeur in Tel Aviv that same year, but the Israel National Opera did its best. The company (and the State of Israel) was barely ten years old, so theirs was a heroic shoe-string production.

In fact, the first Jewish Nabucco evokes a minor European opera house before World War II or even World War I. Apart from the two suntanned sabras in pointy helmets, we might be looking at Brno or Cluj fifty years earlier —with costumes recycled from other operas.

The ultimate Israeli Nabucco came fifty years later —in a richer, more confident country eager to fix itself on the map of international music festivals.

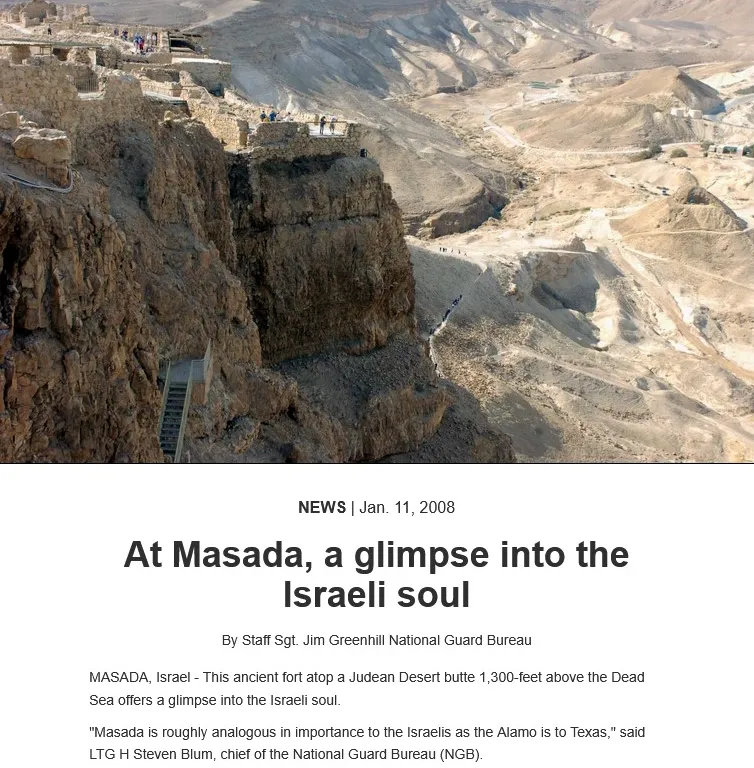

They found their own Arena di Verona in the heart of the Judean desert at one of the most mythic sites in the Holy Land —the mountain fortress of Masada overlooking the Dead Sea.

King Herod the Great built a lavish hill-top retreat in 37-34 BC, but Masada was hallowed a century later by the Jewish patriots who died there after a harrowing siege in 73-74 AD.

In Jerusalem, the First Temple was destroyed by the Babylonians in 587-86 BC— setting the stage for Verdi’s Nabucco.

The Second Temple was destroyed by the Romans in 70 AD— with the fatal siege of Masada to follow.

The producers of this Nabucco focused on both and neither— situating Israel and the Israelites in a perpetual Middle East, battered by wave after wave of invasion and conquest.

Lots of soldiers, more or less medieval, but who and when exactly?

The Ummayads took Jerusalem in 638 AD… the Abbasids in 750… the Franks in 1099… the Ayyubids in 1187… the Mamluks in 1250… the Ottomans in 1517…

Are we looking at any or all of the above?

Meanwhile ...once upon a time and now once again... there is a Jewish state in Israel.

And amidst everythng else, we have Nabucco at Masada.

In 74 AD, more than a thousand Jews killed themselves here rather than surrender to the Romans —in a setting of epic grandeur.

Masada is thus a place that consecrates patriotic rituals, where gestures all seem larger than life. Prestige military units come to pledge their service after comradely tests of endurance (usually strenuous hill climbing in the desert air).

Nearly two centuries ago, by way of Nabucco, the Italian Risorgimento appropriated the age-old Jewish struggle. Then at Masada, the Israelis took it back with interest —at very long last.

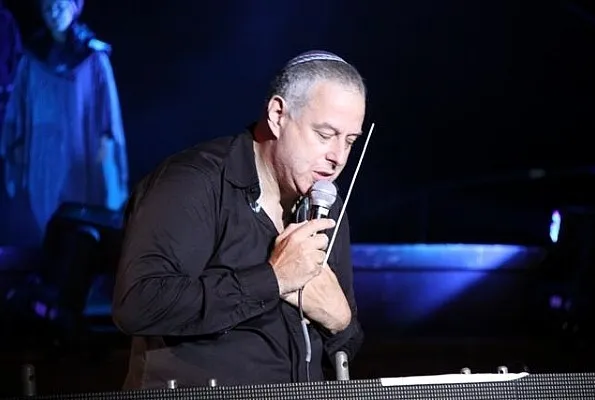

"When “Va, pensiero” was finally played in Act III, the audience (predictably) called for an encore, which was granted by Oren.

Several critics described this as the highlight of the evening and Zvi Goren, writing for Israeli arts online magazine Habama, even described the chorus as “this ultra ‘national’ piece by Verdi... ‘Va, pensiero,’ or for us, ‘On the Rivers of Babylon’ about longing for a homeland and freedom.”

But twice was not enough: once the encore was over, rather than proceeding with the rest of Act III, Oren responded to demands for a second encore by turning to the audience with an improvised microphone saying, “It is a dream come true to perform this slavery song in this holy place.”

He then invited the audience to join in a third rendition of the chorus.

[From Rachel Orzech, Nabucco in Zion: Place, Metaphor and Nationalism in an Israeli Production of Verdi’s Opera, 2015]

I don't know if Va Pensiero was ever performed three times in a row in any other venue. Even in Italy, a single encore was probably the limit (and in some countries, even that is beyond the pale).

Did anyone yell “Viva Verdi" or "V.E.R.D.I.” at Masada, I wonder? Maybe a visiting Italian or an academic specialist? I haven’t found live recordings, so I don’t know.

Nothing, however, would surprise me less than cries of “AM YISRAEL CHAI!” (“The People of Israel Live!”) —since that is what visitors shout off the mountain top, to catch the echo from the surrounding hills.

In the last fifteen years, Daniel Oren directed four major productions of Nabucco.

First came his 2010 Masada Nabucco, a resolutely Jewish story set in a timeless Middle East.

Then came his 2017 Arena di Verona Nabucco, an exuberant nineteenth century tale of Italian national aspiration.

Then came 2021 and Oren's second Arena di Verona Nabucco...

A riveting Holocaust drama —with lagers, gas chambers, crematoria and the rest.

While the Nazis are relentless, the producers didn’t hand the Italian Fascists a free pass.

Perhaps the creepiest scene was one of the least overtly horrible —a sprightly “Strength Through Joy” event at the Mussolini Forum in Rome.

The Shoah-inflected Nabucco was having a moment. This decidedly less baroque iteration played In London that same year.

Still, the tricolor flag-waving was far from done.

Trieste had a special claim to the Risorgimento, to Giuseppe Verdi and to Nabucco in particular.

This cosmopolitan port city— the Dual Monarchy’s chief outlet on the Mediterranean— linked Italy, Central Europe and the Balkans.

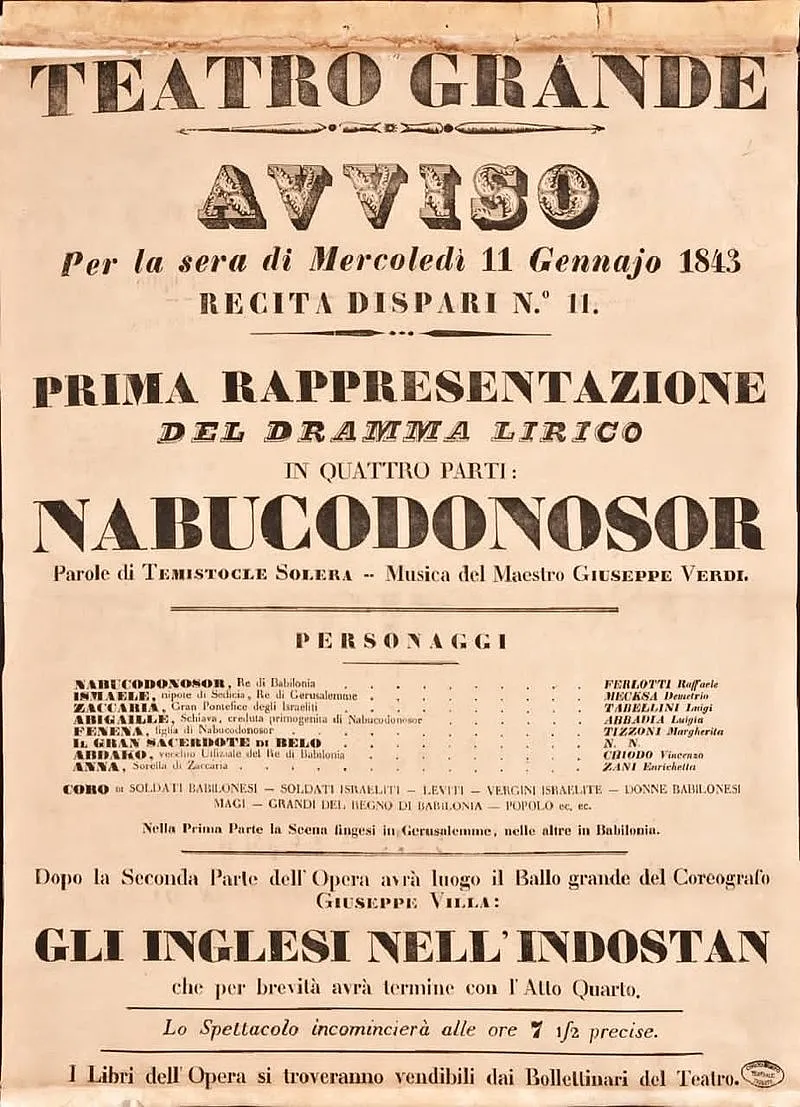

Its resolutely Italian opera house (now known as the Teatro Verdi) quickly developed a relationship with that exciting young composer— premiering Nabucco on 11 January 1843, its third production after Milan and Venice.

At the Teatro Verdi, they knew Verona’s 2017 Risorgimento Nabucco and liked what they saw— but didn't want to import mid-nineteenth century Milan.

Nor did they want to make a thing of Jews and the Holocaust —like Verona 2021 —facing down Trieste’s own dreadful history.

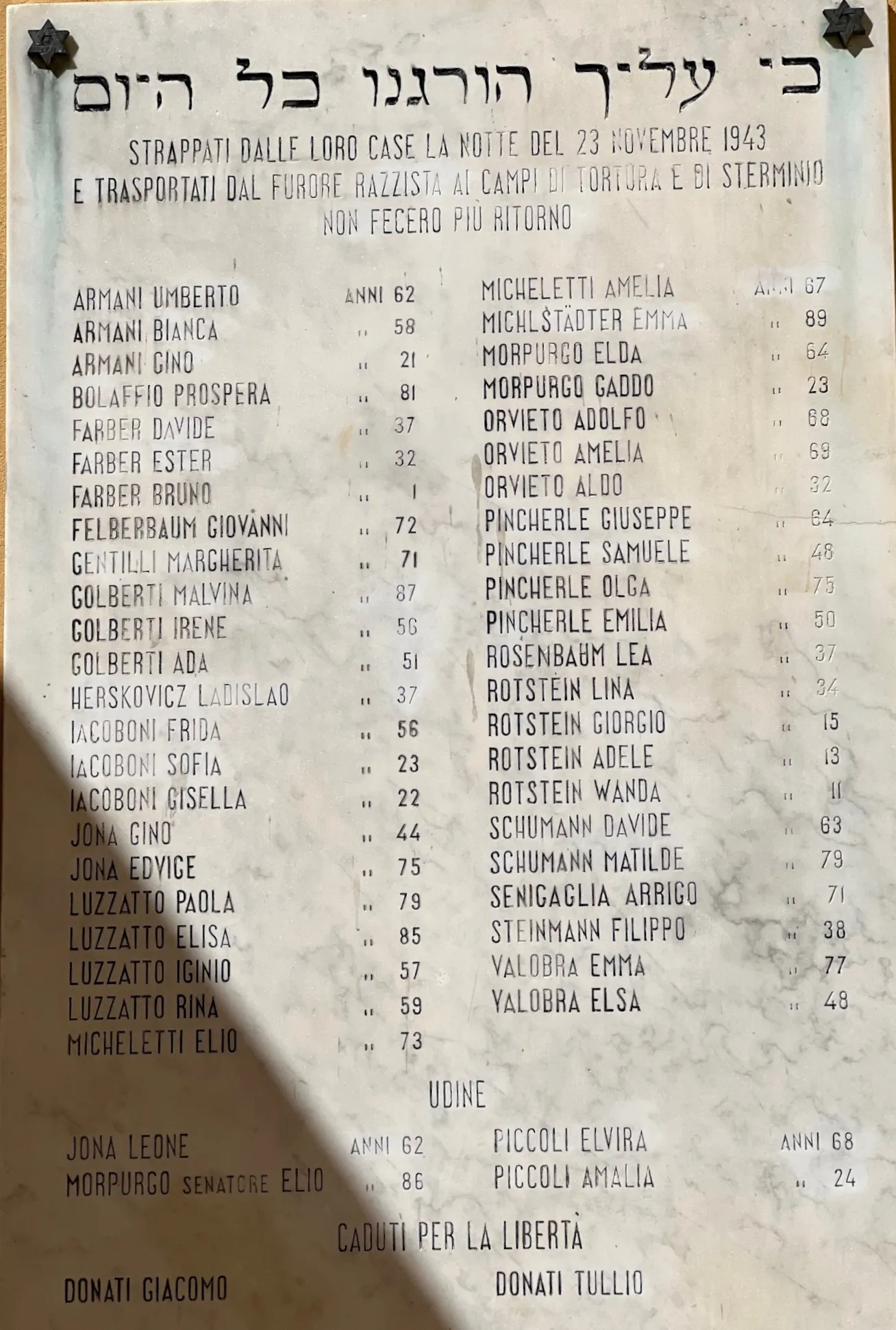

Before Fascism and Nazism, Trieste had been a vibrant center of Jewish life, with a community numbering some 6,000 in 1938, 1,500 in 1945 and 600 today.

In Trieste, the horrors of the not-so-distant past are never out of sight or mind— whatever they put on stage at the Teatro Verdi.

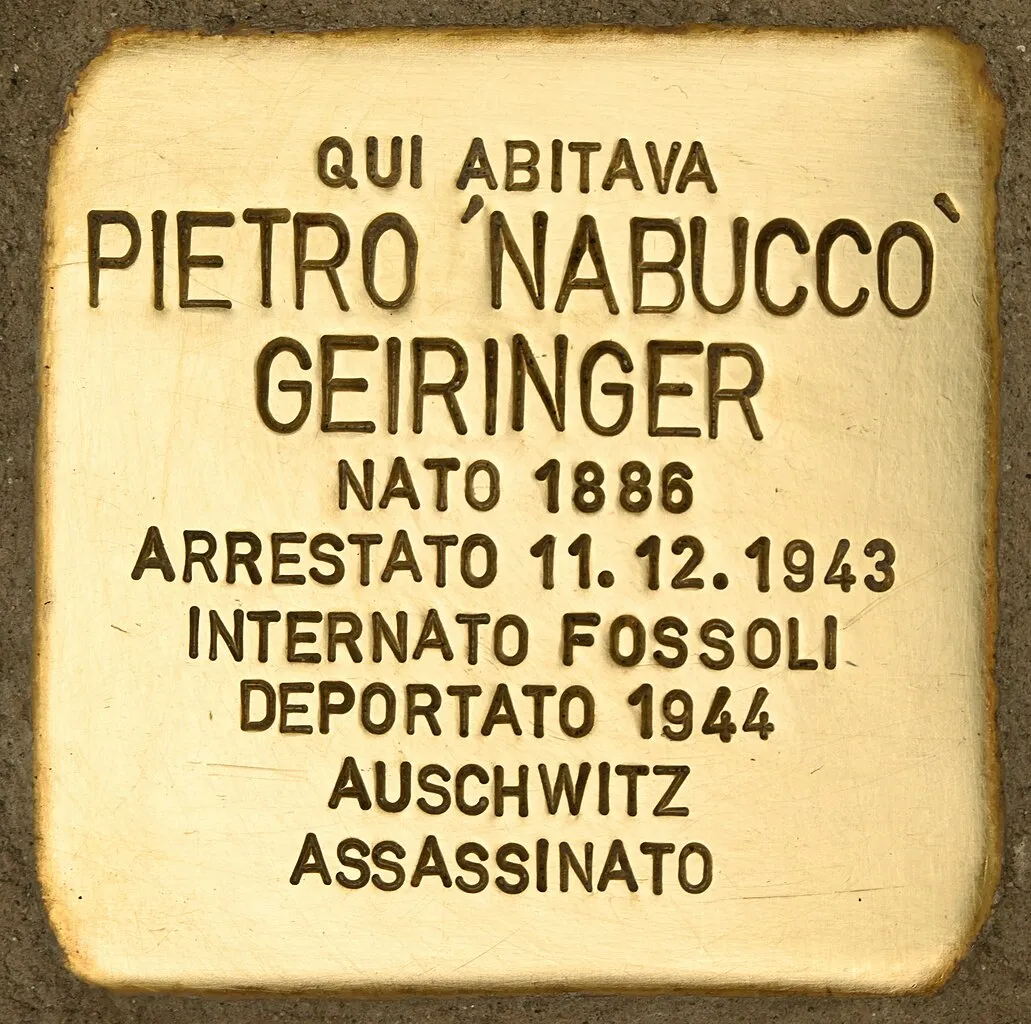

Within city limits, we can visit the only Nazi death camp in Italian territory (complete with crematorium). And more or less everywhere, we find "stumble stones" imbedded in the pavement, marking places where Jews used to be.

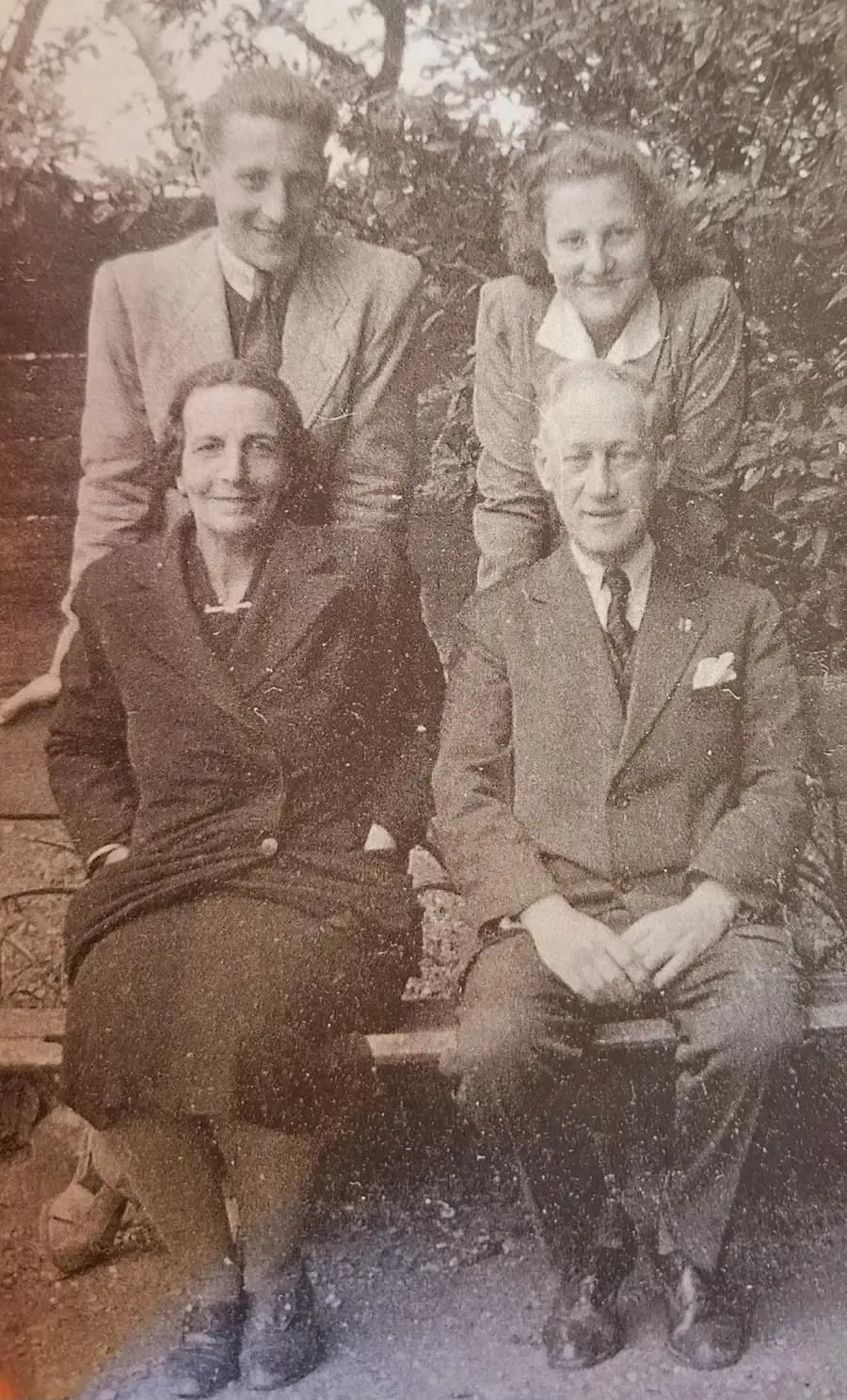

We know quite a lot about the Geiringer Family, which was well-established in Trieste. Pietro’s father Eugenio was a leading architect and Pietro himself co-director of the Assicurazioni Generali —the great insurance company based in that city.

What we don't know is how Pietro came upon the nickname "Nabucco" and what it meant to him, his family and his friends. If you have any insights, please get in touch!

(13) WHAT'S IN A NAME ("Goldberg", for example)?

Going back to the beginning:

Why did I assume that the Risorgimento hero Antonio / Anton / Antal Goldberg was Jewish?

Is that a serious question?

It has been noted (on more than one occasion) that Goldberg is less a name than a punch-line.

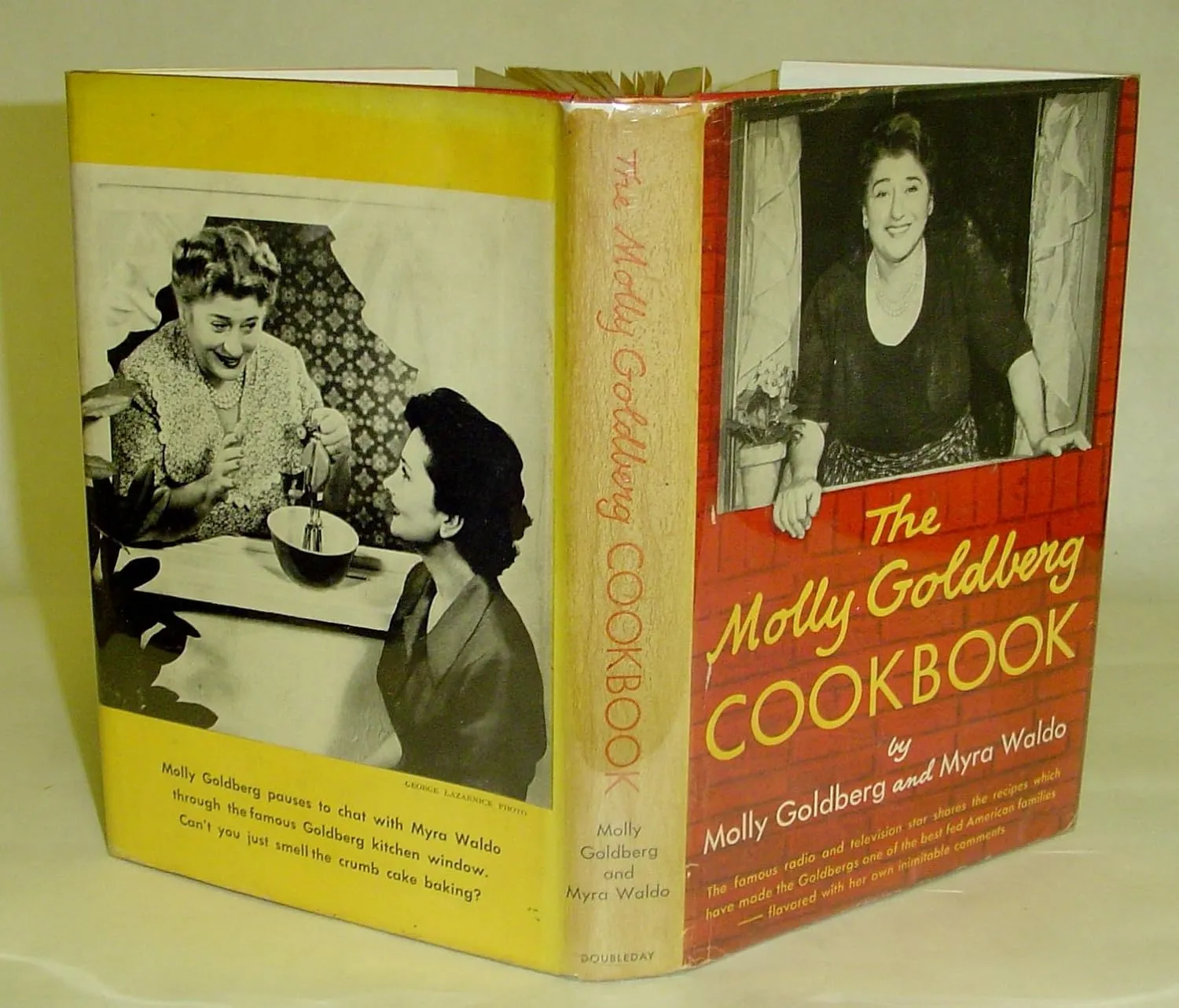

A legendary star of radio, television and cookbooks opted for "Molly Goldberg" because her own "Gertrude Berg" wasn't Jewish enough.

.webp)

Adam F. Goldberg didn't need to rack his brain when branding a sit-com focused on his young Jewish life in the Philadelphia suburbs in the 1980s.

Bill Goldberg (6'2", 285 pounds) put on one hell of a show for 20 years in the WWE but no one pretended that much of the fun wasn't the dazzling improbability of his real-life name.

“Bill Goldberg sounds like an accountant.” World Wrestling Entertainment macher Vince McMahon nailed the problem in a 1997 interview with the aspiring ring celebrity.

Bill’s solution, however, was to feature it —not fix it— flaunting a mononymous GOLDBERG. And the rest is history…

When it comes to sheer oddity, has anyone ever made sense of this?

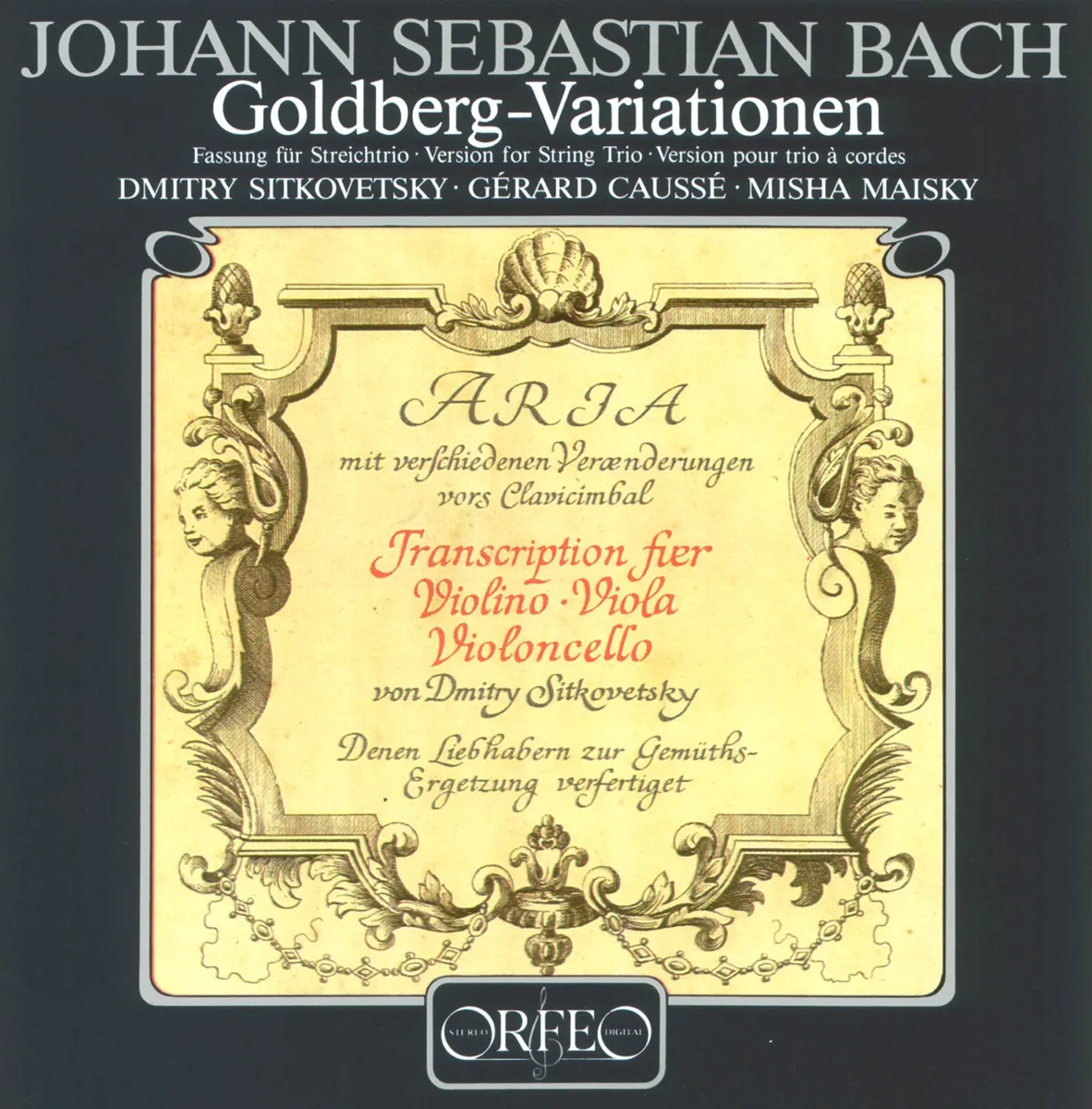

Although "Goldberg"— “Mountain of Gold”— is the ultimate Ashkenazi surname, Johann Gottlieb Goldberg (1727-56) was not Jewish at all.

This German keyboard virtuoso and composer from Gdansk was probably the first to perform Johan Sebastian Bach's celebrated Aria with Thirty Variations, which forever bears his name.

Now we come to the other Goldberg Variations.

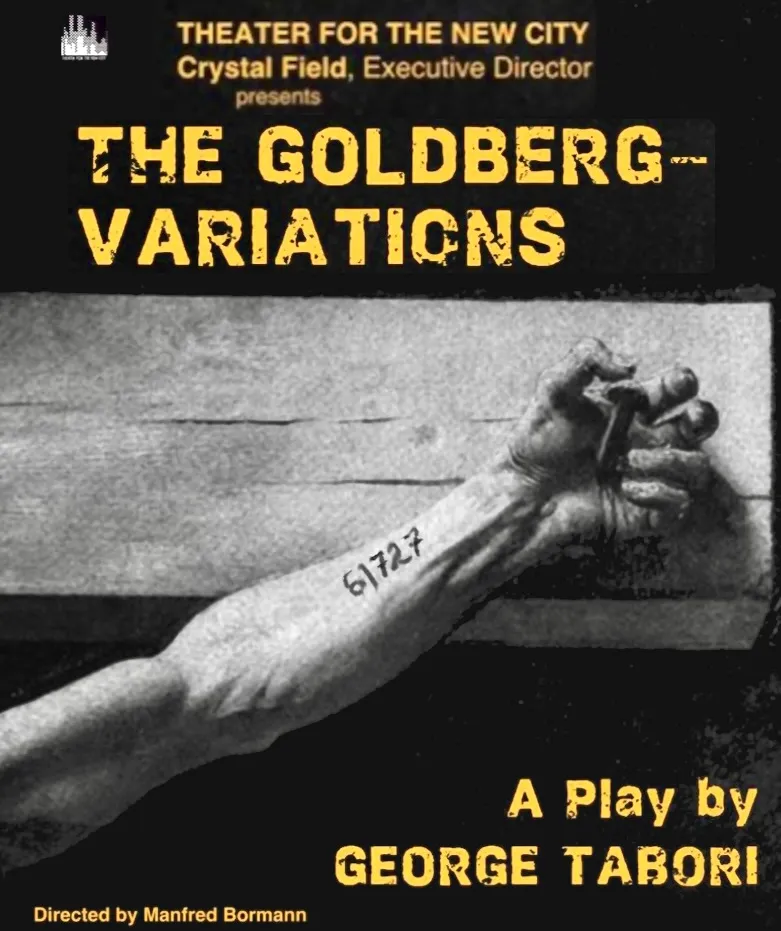

George Tabori's rollicking farce was first performed in Vienna in 1991— in German as Die Goldberg-Variationen, just like the Bach composition.

A perfect storm, you might say...

Who better than a non-Jewish Goldberg to embody the age-old complexity of Jewish identity?

And who better than this particular playwright to jump into the middle?

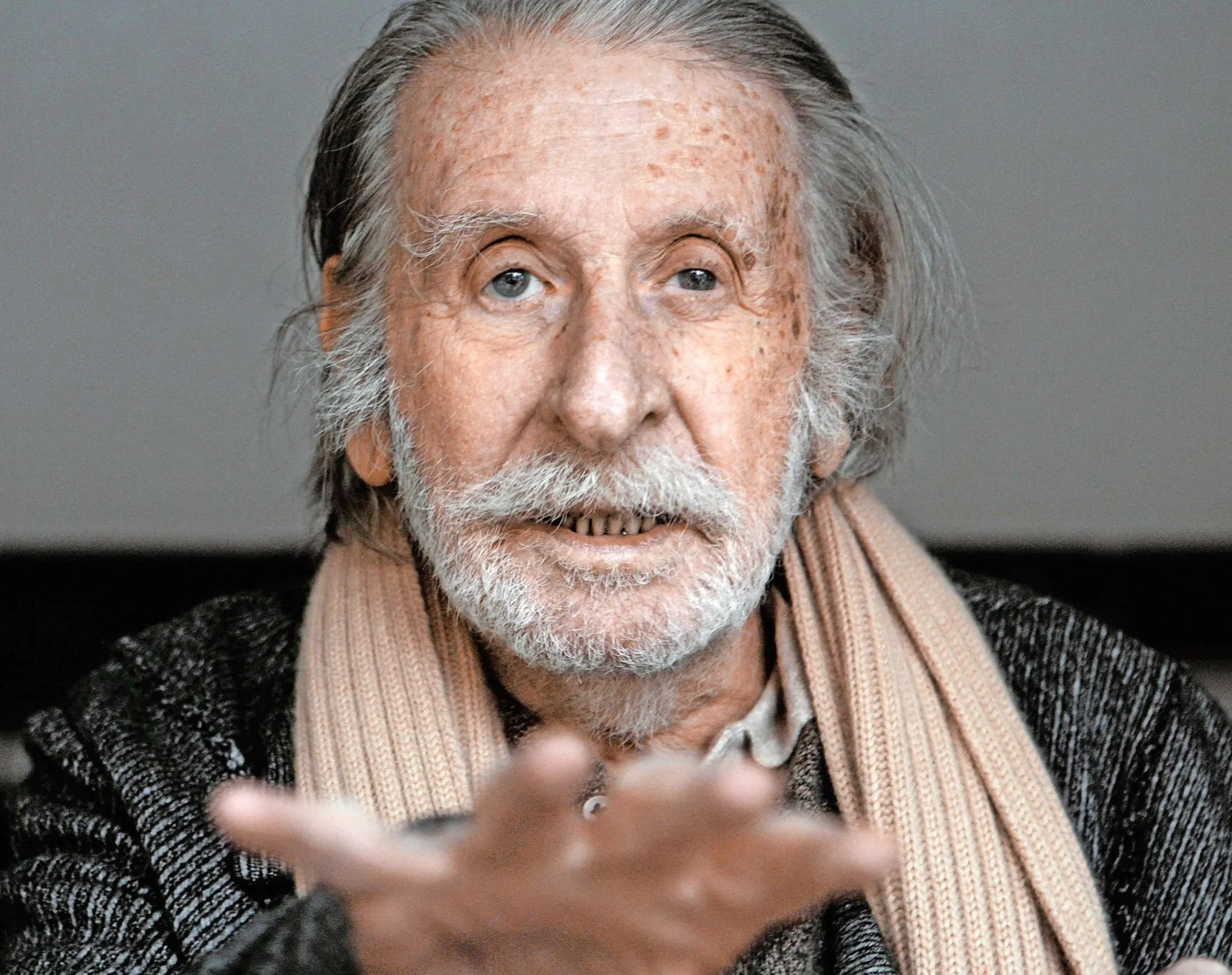

György Tábori / George Tabori was born in Budapest of secretly Jewish parents and did not learn of his troubling heritage until he was seven years old.

Still, it was enough to send him into long exile in various countries and his father to death in Auschwitz.

Then there is the splendidly kaleidoscopic word VARIATIONS…

Random repetition that isn’t random at all…

Let’s put on a show! In fictive Jerusalem!

An acerbic back-stage comedy, mixing and matching the always-colorful disasters of the Jewish People —in both the Old and New Testaments.

Mr. Jay (think Jehovah) directs the play. His assistant Goldberg is Jewish (unlike Johann Gottlieb) and an Auschwitz survivor (unlike Tabori’s father).

The Creation, the Fall of Man, Isaac’s barely averted sacrifice, the Worship of the Golden Calf, the Crucifixion of…

Dreadful jokes come thick and fast. Trauma as a one-liner... A shtick-fest for the ages!

Antonio / Anton / Antal Goldberg’s peregrination through the lower reaches of the Habsburg military might not seem a "traditional" Jewish career track —if he was, in fact, ultimately Jewish (see Part 1 of this series).

Still, soldiering was probably an easy default for anyone of any persuasion who was at loose ends. For a young man in his early 20s, heading off to the Mediterranean port of Trieste in more or less Italian-speaking territory might have had a Foreign Legion appeal.

.webp)

There are endless jokes about misspellings on tombstones, but I like to think that this one would have delighted George Tabori as much as it delights me. (Antonio Goldberg, after all, was a fellow native of Budapest.)

In Italy —as I learned in countless banks, hotels, post offices and airports —the name "Goldberg" might as well be Turco (Turkish, as they say). The collision of three consonants ...LDB ...with nary a vowel in sight, is not for the faint of heart.

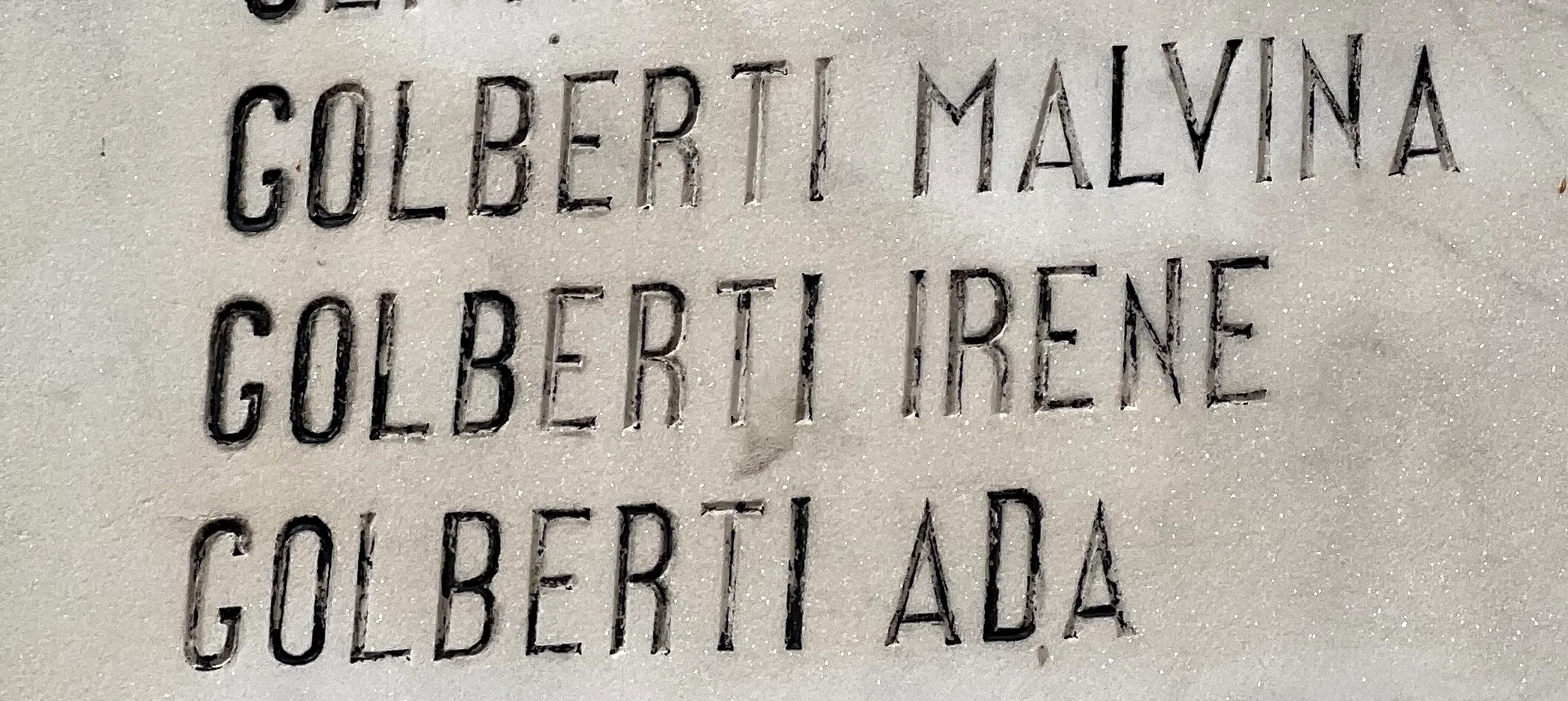

In the case of the Goldberts of Gorizia, it was the "d" that dropped out when they shifted to an Italianized "Golberti". ("Goldbert" means "glitter of gold", paralleling the more frequent "Goldschein".)

"Edward" was never a problem for me, coming up close on "Eduardo". But as for GOLDBERG... one of the first things I learned on Italian soil was the old city-based spelling device:

Genova Otranto Livorno Domodossola Bergamo Empoli Roma Genova.

Thereby hangs a tale...

Once upon a time, back in my grad student days in Florence, I often visited friends In Spoleto for Italian holidays— Christmas, Easter and the like. (I always thought of them as “Italian”, not “Catholic”. Actually, I still do.)

Spoleto was an old-fashioned Umbrian town, very down-home but gaining international attention through its annual arts festival.

In those days, Italian rail travel was more of an adventure than now (pre-Eurostar, pre-online booking) —with antiquated trains and erratic connections.

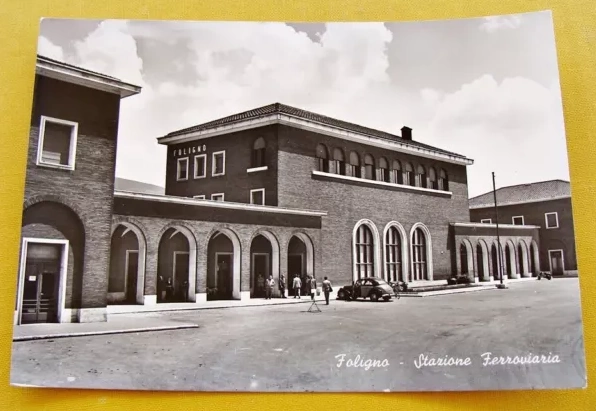

Traveling from Florence, I could usually make it as far as Foligno (about 20 miles from Spoleto) with little difficulty. But then I had to wait for a sporadic local that stopped constantly when it moved at all.

Friends would pick me up at Foligno Station whenever possible —saving time and frayed nerves. "Right between the turtles” was the designated spot.

One sunny afternoon, the day before Easter, I was killing time, waiting for my friend Giuseppina Silvani to appear.

But a half hour passed and there was no Giuseppina (those were pre-cell phone, pre-SMS days). Sitting on the edge of the fountain, I could just hear announcements from inside the station.

One of these caught my attention: "Il signor passeggero tedesco, il signor Montagna d'Oro, è pregato di rivolgersi alla direzione della stazione."

To wit: “The German gentleman passenger, Mr. Mountain of Gold, is kindly requested to apply to the administration of the station”.

Montagna d’Oro? What a funny name for a German! Then after several increasingly insistent repetitions, the penny dropped.

Montagna d’Oro? In German? Sounds like “Goldberg” to me!

What to do? Was I really going to accost the station master (a friendly middle-aged woman, as it happened, in a visored Ferrovie dello Stato / National Railways cap) and launch a topsy-turvy story?

“Well, I’m a passenger but I’m not German and my name isn’t Montagna d’Oro… except sort of…”

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.