GOING TO THE INDIAN: Across Florence’s Cascine Park and off the Edge of the Earth (Part 1)

CONTENTS:

(1) WHO WAS "THE INDIAN"?

(2) LE CASCINE: FROM MEDICI FARMLAND TO PUBLIC PARK

(3) CRICKETS IN THE CASCINE

(4) CRICKETS vs CAMELS

"Che bella giornata! Perché non facciamo due passi?"

"What a nice day! Why don't we go for a little walk?"

"Bene! Basta non andare all'Indiano!"

"Okay! But not all the way out to the Indian!"

*

"Maria? Non si vede piu! E' andata a vivere all'Indiano."

"Maria? We never see her anymore! She went off to live at the Indian."

*

"Queste nuove scarpe? Dovevo trascinarmi fino all'Indiano a trovarle!"

"These new shoes? I had to drag myself all the way out to the Indian to find them!"

"Trek to the edge of the earth..." "Sail off the outer banks..." Or, more mundanely, "Shlep all the way across town..."

The Indian has embedded himself in the Florentine consciousness as the local Ultima Thule—a mythical island somewhere north of Britain, where nature dissolves into nothingness and there is no way back.

(1) WHO WAS "THE INDIAN"?

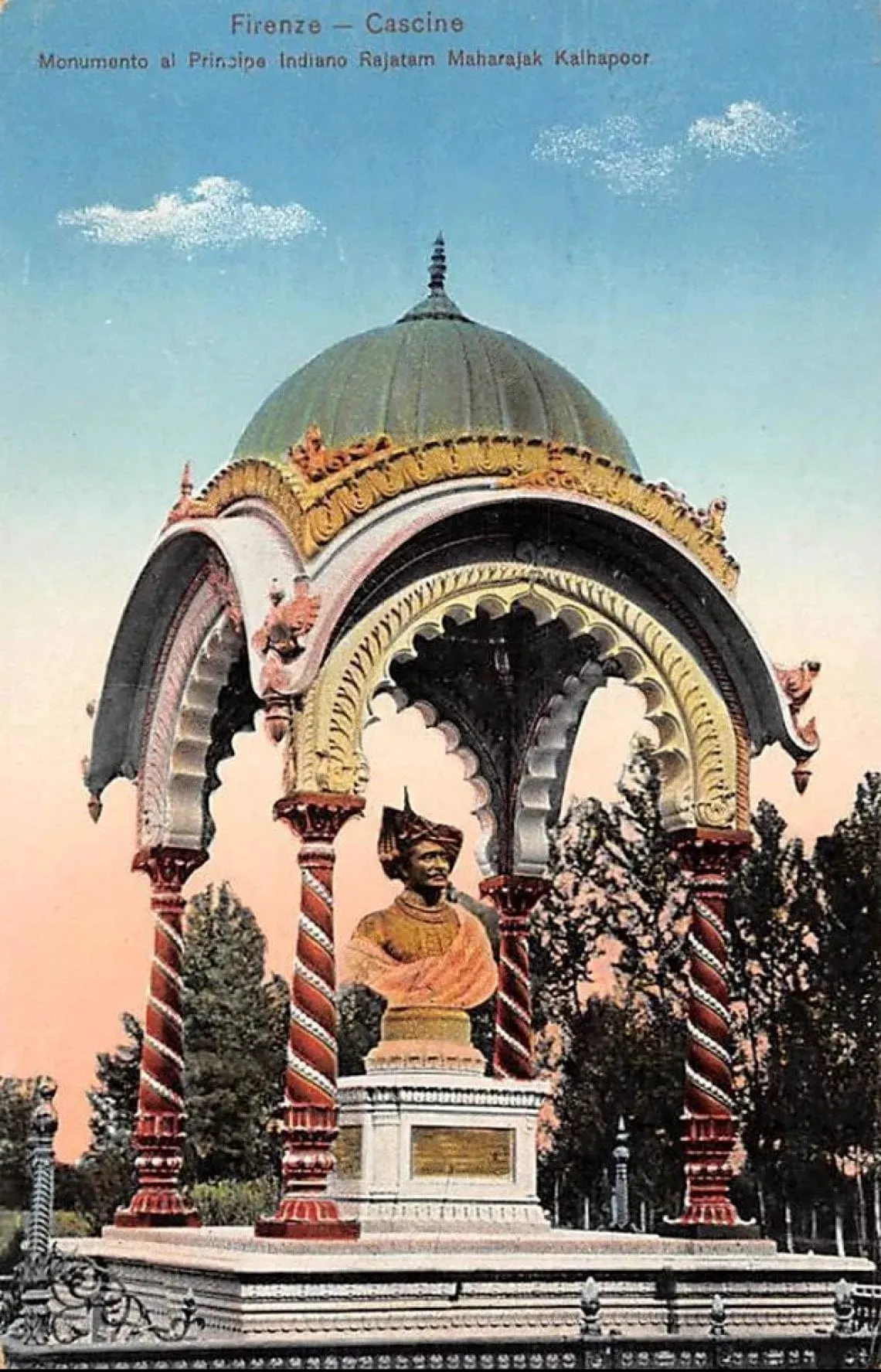

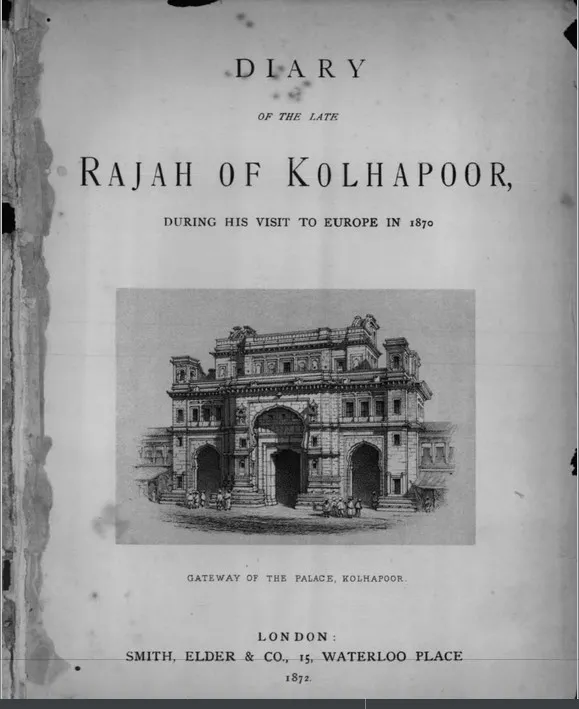

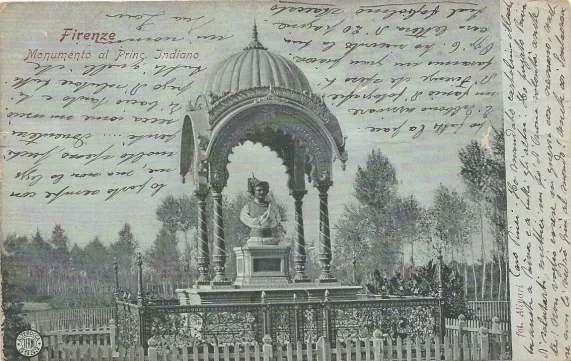

According to his full style, he was Shrimant Rajashri Rajaram I Bhonsle Chhatrapati Maharaj Sahib Bahadoor, Seventh Raja of Kolhapoor (born Kolhapoor 1850-died Florence 1870).

In 1866, the sixteen year-old Rajaram Chuttraputti ascended the throne of Kohlapoor, a mid-sized principality in the northern region of Maharashtra. In 1870, he traveled to England to exchange courtesies with Queen Victoria, then headed south through Germany to Italy, stopping in Florence at the Hotel de la Ville in Piazza Ognissanti. This was the newest and grandest hostlery in what was then the capital of the united Kingdom of Italy.

The story of the Indian Prince's visit to Florence is quickly told. He took sick while traveling and died on November 30, 1870, soon after his arrival, without appearing at the court of Vittorio Emanuele II or even venturing into the city.

Rajaram Chuttraputti's entourage then faced the unprecedented task of organizing a grand Hindu funeral on Tuscan soil—in greatest possible haste.

Two months after the event, Sir Augustus Berkeley Paget (British Ambassador Extraordinary to the new Kingdom of Italy) wrote Marchese Emilio Visconti Venosta (Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs).

He enclosed a copy of the formal report issued by the Director of the Florentine Municipal Police and the Secretary of the local Sanitary Commission.

In the suave diplomatic language for which he was famed, Augustus Paget bore "witness to the very great kindness and consideration evinced by the Syndic (ie. Mayor) on the occasion in question...and his earnest and successful efforts in overcoming the difficulties of various kinds which stood in the way of the performance of a ceremony so entirely novel in this country."

The envoy praises Mayor Ubaldino Peruzzi de'Medici's "high and enlightened sentiments" in allowing "the rites of their religion". In fact, the city official was defending the liberal credentials of the new Italian monarchy, which sought to distance itself from the doctrinal prejudices of the past—especially when Britain (India's colonial overlord) was fronting the Rajah's case.

Cremation was forbidden by law in that Catholic land, so Paget needed—at very least—a secular dispensation from Peruzzi de’ Medici. The mayor granted this promptly but on stringent conditions, as recorded in the official report.

The funeral had to take place under the cover of darkness—beginning at 1am, in order to attract as little attention as possible. "The place chosen for the purpose was the extreme point of the Cascini (park), on the bank of the river Arno, in a deserted and open esplanade."

For Hindus, the confluence of waters is immensely significant for purification rites. Not only was the designated point of land washed by the Arno River, it was at its juncture with the Mugnone.

The site was "deserted" and "open"—as the report repeatedly emphasizes—away from "the crowding of the curious public". While order and decorum were legitimate concerns, there was also the Catholic reaction to "pagan" rites".

Instead of a public procession, the Prince's body was transported—grotesquely enough—in the hotel omnibus, with the mourners balancing the body on their knees. (At that hour, the horse-drawn conveyance was presumably not needed to ferry guests to and from the train station.)

Still, word got out. "Notwithstanding the early hour, and the bad weather, a number of other carriages and a numerous crowd followed the cortège."

Most of the curiousity seekers (both of the carriage-owning and pedestrian classes) lost interest in the long hours between the firing of the pyre at 2am and its extinction at 10am.

At that time, the late prince's entourage returned to the hotel with his ashes, which they took back to India and eventually consigned to the waters of the Ganges.

Back in Kohlapoor, the young Rajah was succeeded by an even younger one (age 8 1/2), in a long series of rulers extending from the Seventeenth Century to the present day. In Florence, however, the ill-fated prince still reigns, amidst the proliferating myths and legends of the Cascine.

(2) LE CASCINE: FROM MEDICI FARMLAND TO PUBLIC PARK

For centuries, the Cascine ("The Farmsteads") had been a vast agricultural estate belonging to the Medici family—extending for three-and-a-half kilometers along the Arno River.

On major holidays (like the Grand Duke's birthday and Ascension Day), the rulers of Tuscany graciously opened their property to the populace for picnics, sports, dances and other rural pastimes.

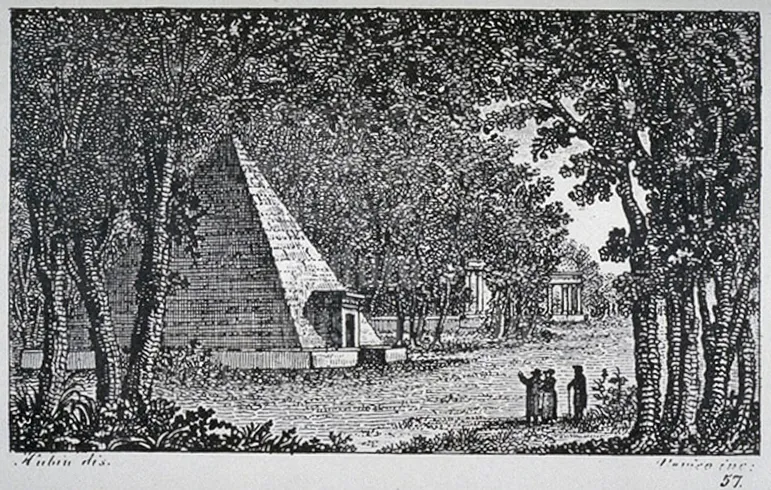

In the nineteenth century, the Cascine became a public park, in the modern European style—with monumental features of the most imposing kind.

The Icehouse (1796) in the Park of the Cascine, in the guise of an Egyptian Pyramid (F. Fontani, "Viaggio pittorico della Toscana", 1827)

Especially during the brief period (1865-71) when Florence figured as the first capital of the united Kingdom of Italy, the Cascine emerged as a fashionable promenade and carriage drive.

After the court moved on to Rome, the Cascine took on a somewhat more popular character, notwithstanding the contruction of a fashionable race course and exclusive sports clubs.

(3) CRICKETS IN THE CASCINE

In 1941, the song Mattinata Fiorentina/ Morningtime in Florence (popularly known as Primavera nelle Cascine/Springtime in the Cascine) was a smash hit within a forty mile radius of Brunelleschi's Cupola but also enjoyed some popularity abroad.

È primavera!

Svegliatevi bambine!

Alle Cascine,

messere Aprile fa il rubacuor!

It's springtime!

Wake up little girls!

In the Cascine,

Mister April is stealing away your heart.

The Feast of the Ascension of Christ (forty days after Easter) was the Cascine's annual star turn.

Children with their parents, grandparents, neighbors and friends flocked to the park for the caccia al grillo (cricket hunt), an ancient local observance lost in the mists of time—supporting a cottage industry of gabbiai (cricket cage makers).

The ultra-Florentine Carlo Collodi pushed local Cricket Culture onto the stage of World Literature in 1883 with Le avventure di Pinocchio. Storia di un burattino (Adventures of Pinocchio. Story of a Puppet).

.webp)

Believe me when I say that no character created by Carlo Collodi (Collodi is the small town near Pistoia that his mother came from; his real name was Carlo Lorenzini) would ever sing When You Wish Upon A Star or Give A Little Whistle. Nor would they be caught dead in a Tyrolean hat or Alpine shorts.

If you meet an Italian who loves the bright and bouncy 1940 Disney film Pinocchio, you can be sure that they are not Florentine—unless they grew up without parents or grandparents reading them the original (an inevitable rite of passage, way back when). Collodi's book is a masterpiece of both Tuscan dialect and Tuscan irony, replete with social satire and moral conventions turned on their heads.

.webp)

At some point, a child colored this alarming illustration from Enrico Mazzanti's 1883 first edition, instinctively highlighting the threats in the fragile puppet's hostile world (which has more in common with Hieronymus Bosch or Franz Kafka than Sesame Street). The Fata Turchina (Turquoise Fairy, Pinocchio's ethereal guardian angel on the left), has her work cut out for her—and then some.

%252520detail%252520enlarged.webp)

(4) CRICKETS vs CAMELS

%252520xx.webp)

No one knows where the annual Ascension Day Cricket Hunt in the Cascine comes from or what it's all about...really.

A children's holiday at first glance, we can also discern ancient courtship rituals and pagan observances of the rites of spring.

And like folk customs everywhere, new elements come and go over the years.

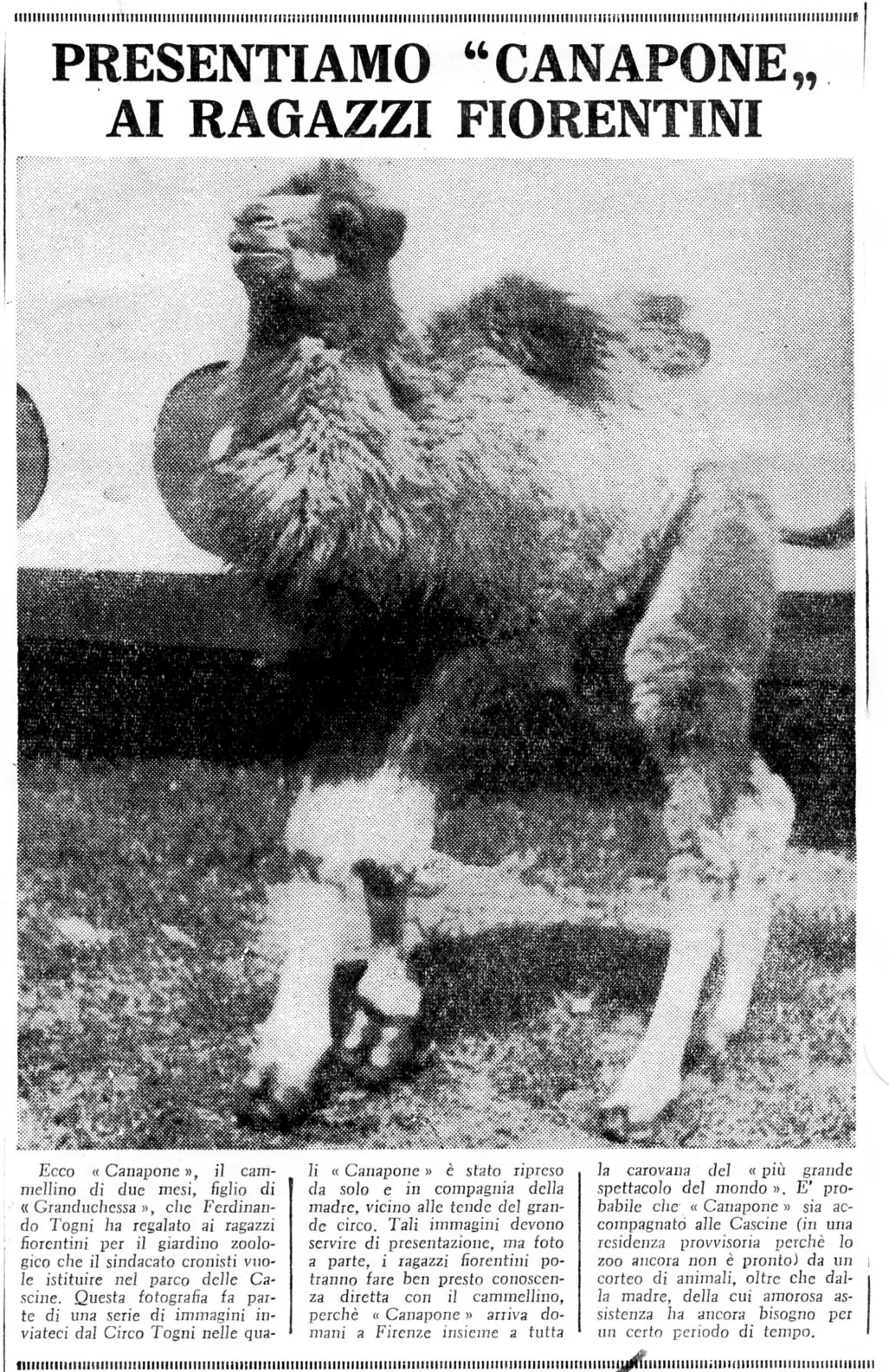

Take the short-lived camel connection. In 1959, circus owner Ferdinando Togni presented a two-month old camel to the city of Florence for their new zoo in the Cascine.

He was named Canapone ("hank of hemp", a local term for a grizzled old man) and immediately became the unrivaled star of the Festa del Grillo.

La Nazione, May 8 1959, "Florentines Yesterday at the Park of the Cascine: Canapone the Camel leads the Historic Cortège at the Festa del Grillo".

In the arch, highly literary idiom of Florentine journalists of that time:

By popular reckoning, at least 150,000 Florentines, with the expected admixture of guests of every lanaguage, brought the park of the Cascine back to life yesterday morning.

For centuries, the poor dear singing cricket played the leading role in this our most most picturesque and romantic folkloric manifestation.

But—who knows how this happens and not only to crickets?—the familiar insect is now forced to lower its wings (not just a little), overtaken by the arrogant ascendancy of other tastes and customs.

Canapone, alas, did not have a long or tranquil run as protagonist of the Festa del Grillo. Only a few months after his début, it was discovered that "he" was a actually a "she"—cammella not cammello, as previously announced. Then on November 4, 1966, she drowned at age 7 1/2 in the tragic flood that inundated much of Florence, including the Cascine and its Zoo.

The poor dear crickets did not themselves emerge as a point of public contention in their own right for another three decdes. In 1999, the Florentine City Council voted to end countless centuries of unspeakable cruelty to Gryllidae—running as fast as they could to stay ahead of a vocal clique of animal rights activists.

The legislation was utterly unworkable and a real treat for the many Florentines who loved seeing their leaders trip over their own politically-correct feet.

While selling crickets might be illegal, what about catching your own? How about "cricket possession" and "cricket paraphernalia"? What do you do with juvenile offenders?

Then there was the "tradition" problem, with revered ancient customs running into new-fangled raised consciousness. Both were sacrosanct for left-wing politicans, including Florence's entrenched Social Democratic city council.

Their ultimate bright idea was that gabbiai (cage makers and sellers) should continue to ply their venerable trade, but they would substitute fake crickets for real ones. Mechanical singing gadgets were promoted as an exciting upgrade from real insects.

Amidst the inevitable surge of public derision came a brief moment of multicultural harmony. Metro-Florence has a substantial Chinese population, mostly on the Cascine side of town. Back in their homeland, they had been celebrating crickets and cricket cages for as long as anyone could remember.

.webp)

The art of zhezhi (Chinese origami or paper folding) can be adapted to grasses and flat leaves. So, the residents of Buozzi, Brozzi and San Donnino quickly flooded the local market with their own hand-crafted surrogates (usually made on the spot, with a significant component of performance art).

These whimsical creatures—100% biodegradable and requiring no batteries—were soon dangling from houseplants more or less everywhere (my own home included). However, the vendors (all conspicuously unlicensed) had no lasting impact on he Ascension Day event and their zhezhi crickets vanished as quickly as they appeared.

The Cricket Festival Without Crickets quickly devolved into a generic pop-up market in the Cascine, with earnest biodiversity exhibits on the side.

Meanwhile, civic officials were hammered by everyday Florentines who had fond memories of bygone cricket hunts. In fact, they far outnumbered the animalisti (animal rights advocates).

"PARK OF THE CASCINE: THE CRICKET FESTIVAL IS BACK BUT CONTROVERSY ERUPTS WITH ANIMAL ADVOCATES. Although abolished in 1999, the event was reinstituted by way of a special waiver to the new law for the protection of animals. However, the crickets have to be released within three days of the festival. Now, the animal advocates are up in arms."

To the astonishment of everyone—probably themselves included—the Florentine City Council took a deep dive into legislative dementia. Council President Eugenio Giani clarified the situation (or not):

" 'This inclusion was symbolic in nature' —Giani explained—'in order to safeguard a traditional civic festivity.' However, a small provision was then devised in defense of insects: thanks to a sub-amendment linked to the special waiver, the insects must be liberated within three days of the celebration."

«È stato un inserimento di natura simbolica—ha spiegato poi Giani—a tutela di una festa tradizionale cittadina». È stato tuttavia escogitato un piccolo accorgimento a tutela degli insetti: grazie ad un sottoemendamento connesso alla deroga, gli animali dovranno essere liberati entro tre giorni dalla festa. (Corriere della Sera, 8 Aprile 2014).

Giani's simultaneous appeal to tradition and symbolism is intriguing, but what enforcement mechanism did he have in mind? Would every cricket collector be followed home from the Cascine, then staked-out for (up to and including) 72 hours—with immediate arrest for eventual non-compliance?

"Horror! The Festival of the Cricket has been re-exhumed with Real Crickets!"

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.