GOING TO THE INDIAN: Across Florence’s Cascine Park and off the Edge of the Earth (Part 3)

CONTENTS:

(9) THE BEAUTIFUL GAME

(10) MORE SPORTS

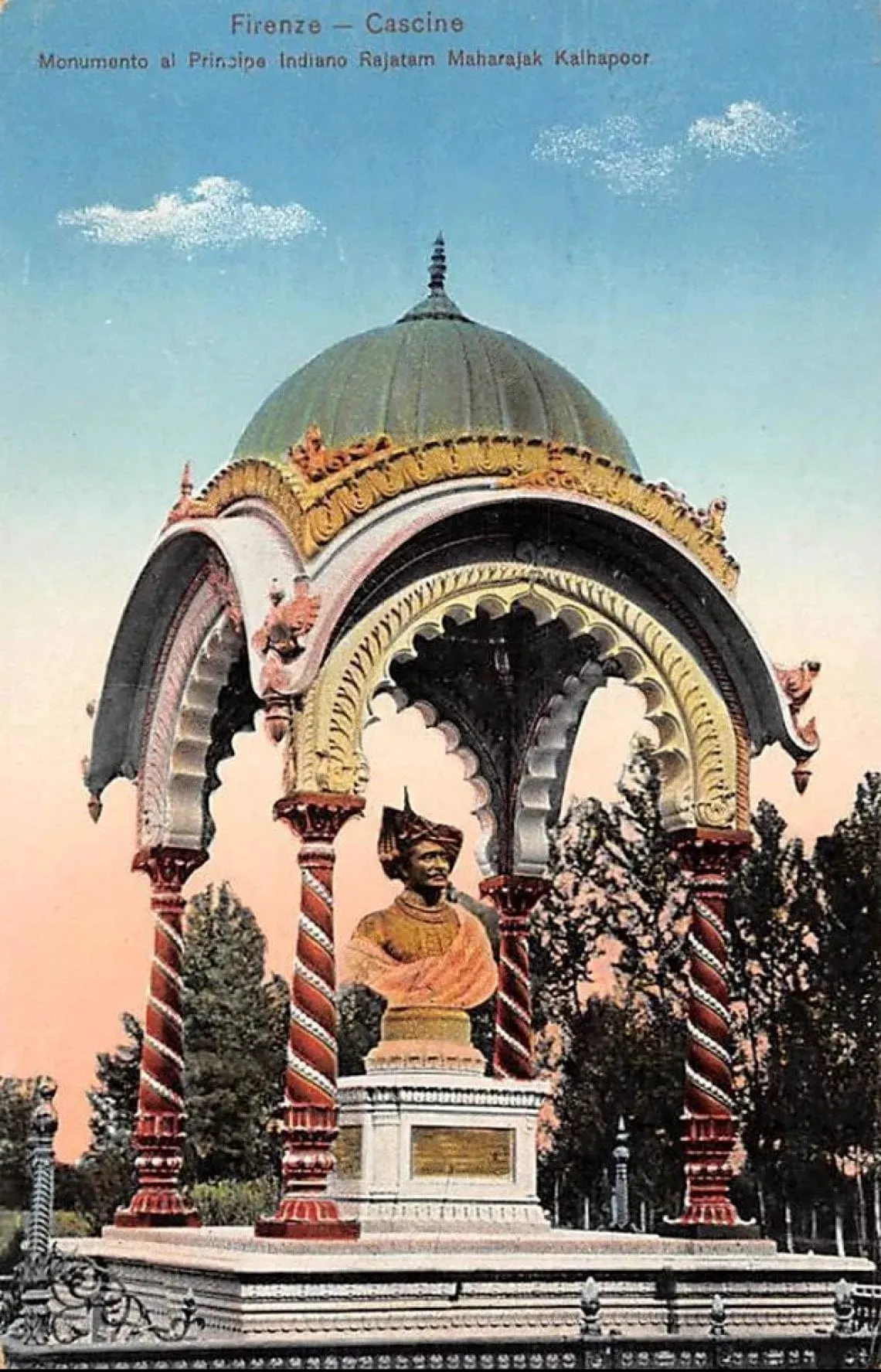

(11) "GO THROW MYSELF OFF THE INDIAN"

(12) THE INDIAN COMES HOME

(9) THE BEAUTIFUL GAME

The past is a world of palimpsests, where nothing is written on a blank page. We read text upon text, with words bleeding through—grabbing at meanings as we go.

What can the letter "U" have to do with Vittorio Emanuele II? (His son was Umberto, but still...) Then there are those red and white scrawls all over the base.

Any Peruvian could give you the answer in a flash.

Lima's Club Universitario de Deportes (University Sports Club) fields a hugely popular soccer team, known as "la U" to its devotees. But why here of all places—in Florence, on the Cascine side of a lingering royal monument?

Context is everything, as usual.

Nearby, on an old wall—large as life and in your face. Alianza, the inveterate rival of Universitario.

Thereby hangs many a tale... Back home in Lima, the century-old Clásico Peruano—Alianza vs Universitario, a cross-town derby—is still the most intense moment of the sports year, punctuated by frequent outbursts of violence.

Alianza (1901) emerged from a rough-and-tumble working-class quarter, while Universitario (1924) was a later association of more-or-less privileged college kids. In fact, the Clásico was once popularly known as Blancos contra Negros (Whites versus Blacks), with racial roots extending back into the colonial past.

Alianza and Unversitario are now fully professional organizations and even national teams. But still, club culture continues to flourish in rich and strange ways.

Firenze and Grone—not just Lima or even Peru. Grone is a smallish but hard-core neighborhood in the metropolitan district of Barranco, with its own spin on Alianza identity.

Back in the Cascine, I am not spotting specialized Grone regalia (which might not have existed back then. The photo is from 2010.) The guy in the middle is wearing a classic (even historic) Alianza jersey, with broad blue and white stripes. His friend to the left has the matching shorts. The yellow and black kit might reveal an aspiring Alianza goalkeeper.

When foreign customs arrive, they attach themselves to local ones with surprisng speed. The Chinese with their zhezhi (origami) crickets come immediately to mind.

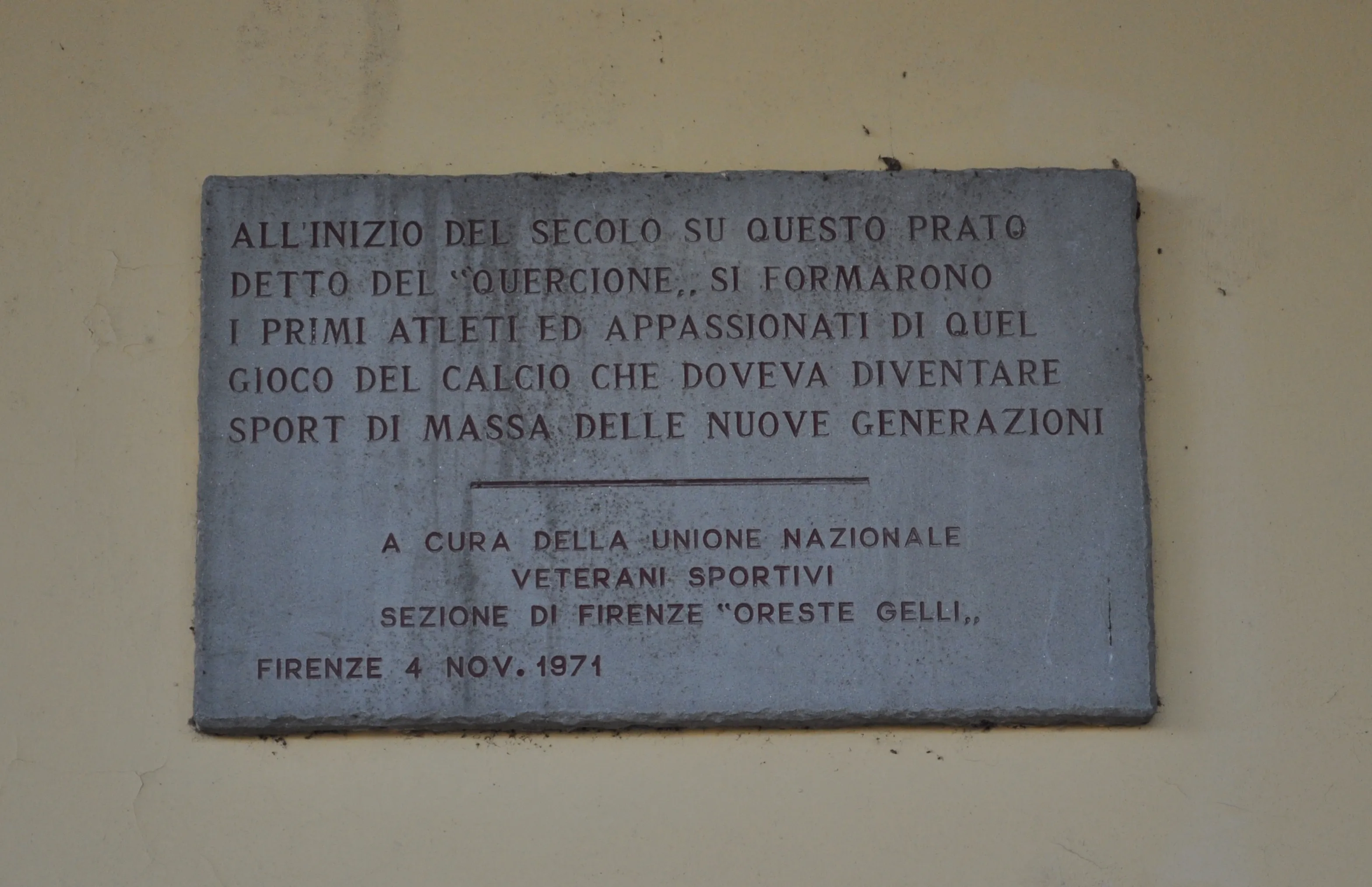

We are still in the Cascine, one field over from the Peruvians' pick-up game. If you are a soccer fan (imported or domestic) there is story after story to tell.

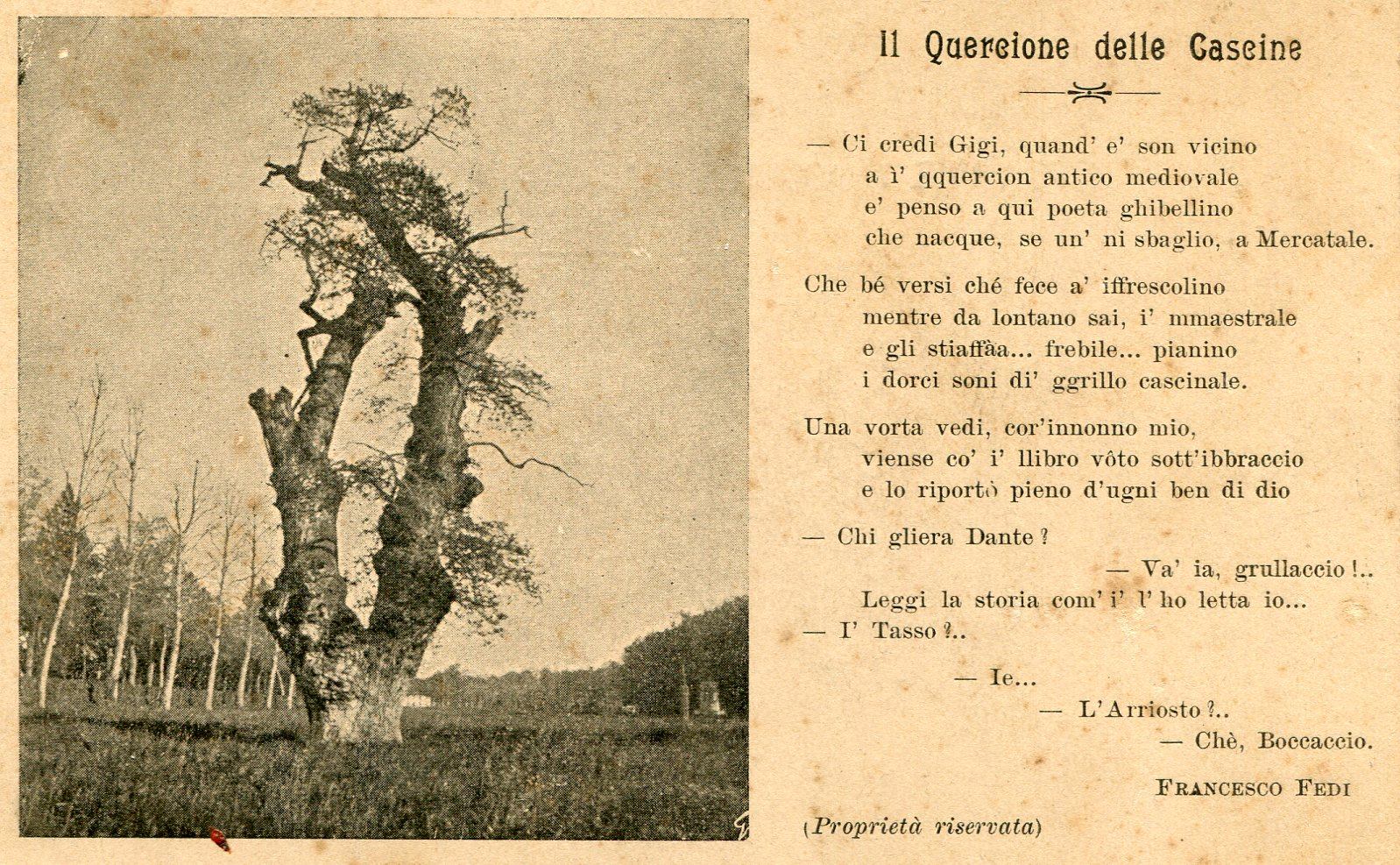

The poet Francesco Fedi had a fine old time playing with local dialect and stringing together literary allusions. How long ago, I wonder, did he generate these verses? (This particular Francesco Fedi seems utterly impervious to web searches.) Maybe Florentine Football had not yet sprung from the sacred soil of the Prato del Quercione?

This rievocazione was sponsored by Florence's two oldest athletic associations: the Club Sportivo Firenze was founded in 1870 (as a cycling organization) and the Palestra Ginnastica Fiorentina Libertas in 1877. Such historic claims can prove elusive, however, since there was a constant whirl of foundations, amalgamations and disbandments in those early years.

The Florence Football Club arrived on the scene in 1898, the Itala Football Club in 1902, the Club Sportivo Firenze in 1903 (refounded to include football) and the Firenze Football Club in 1908. Then in 1910, a faction split off from the Firenze Football Club and joined the venerable Palestra Ginnastica Fiorentina Libertas, eventually giving rise to the Associazione Calcio Fiorentina (1926)—still the preeminent hometown team after nearly a century.

QUELLI DI SEMPRE = THOSE WHO HAVE ALWAYS BEEN HERE

Quelli di Sempre is more than a masterpiece of mythic self-identification, it is the name of a specific tifoseria (supporters' group) and a newish one at that, founded in 2012.

THOSE WHO HAVE ALWAYS BEEN HERE is a fan club with an agenda, expressed in the (purposely?) faded motto attached to their main banner. Owners, sponsors and administrators come and go (as everyone seems to know, except the owners, sponsors and administrators themselves). Meanwhile, home-grown fans persist generation after generation.

CONTRO IL CALCIO MODERNO = AGAINST MODERN FOOTBALL

Theirs is not a nostalgic appeal for old-timey re-enactments, with guys hugging the edge of a rudimentary field staked out in the Prato del Quercione. Instead, they are making a case (against heavy odds) for a present-day football that really matters—local in spirit and free from the corrupt macchinations of the powers-that-be.

Funny how sports tribalism both divides and unites... While fan culture is esentially local, the vital impulse knows no bounds. In their heart of hearts, the protagonists of Quelli di Sempre Firenze and Alianza Grone Firenze understand each other perfectly, as they struggle to secure what is rightfully theirs in an increasingly corporate world. And Florence being Florence, we can also bet that they buy their spray paint in the same discount megastores—out along the highway, past the Indian, on the edge of town.

(10) MORE SPORTS

In 1563, Cosimo I de'Medici (Duke of Florence and Siena, soon to be Grand Duke of Tuscany) designated a vast tract of land outside the northwestern gate of his capital as a princely preserve. According to his plan, Il Parco delle Cascine—or more simply, Le Cascine—was destined to nurture livestock and host hunts.

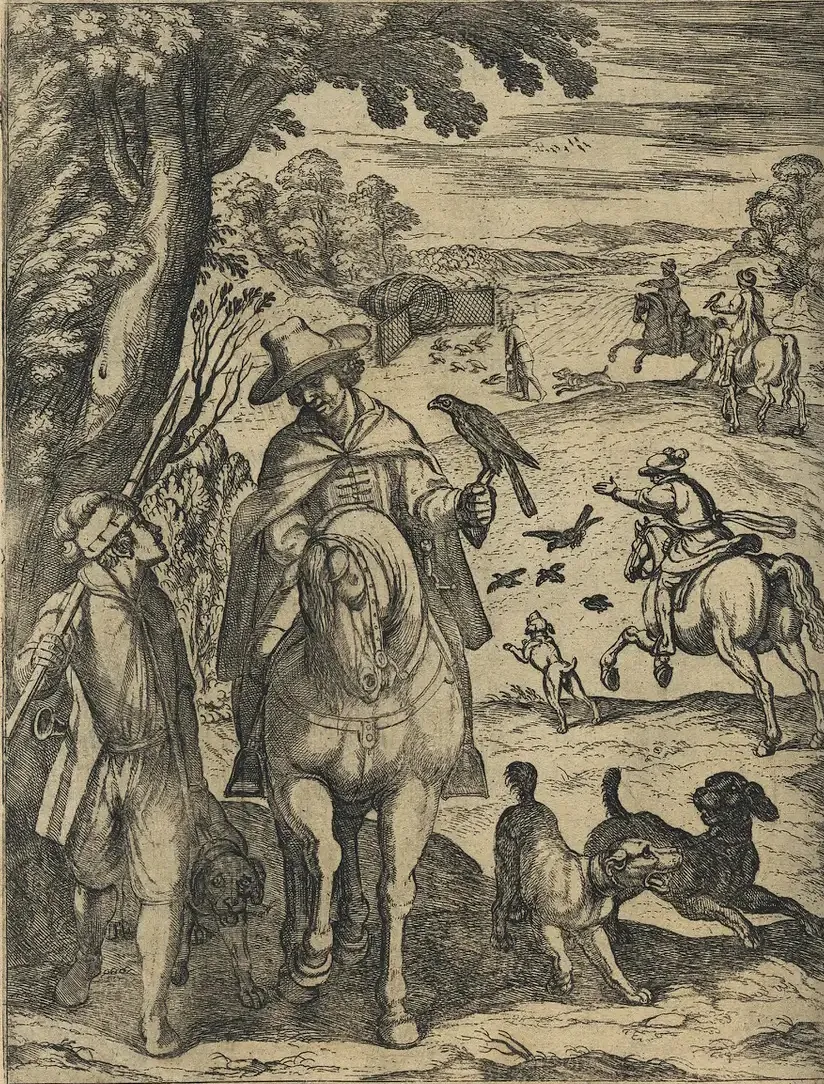

The hunts that the Medici had in mind were mostly staged affairs, with birds, rabbits, deer and boar driven into ingeniously constructed enclosures where they could be picked off at will—after an invigorating ride through luxuriously open countryside. Hunting was the ultimate aristocratic diversion, since it required an abundance of land, horses, dogs and servants, plus guns and other expensive equipment.

On a few special occasions, like the Grand Duke's Birthday and Ascension Day (forty days after Easter and the traditional date of the annual cricket hunt), the park was thrown open to the public for walks, dances, picnics and games. In 1630, Stefano della Bella—a prolific Florentine draftsman and printmaker—captured the range of activity in an encyclopedic rendering.

Della Bella shows an intriguing mix of social types (all male, it would seem), briefly sharing a privileged space. Shoeless vagabonds (to the left) huddle amidst cast-off melon rinds, while aristocratic hunters (to the right) assemble beside handsome horsecarts (the solid, open type favored for country use).

One seated figure (to the left) proffers a long hunting rifle, another (to the right) grasps a fancy halberd (the sort used for the chase, not war).

In the center section, della Bella focuses on the tree-lined grand avenue, chief artery of the Cascine.

To the left, he features an exotically garbed, dark-complected figure with an elaborately feathered head-dress, accompanied by a man with an elegant greyhound. This was a breed prized for both racing and hunting, unlike the lone mongrel curled-up below.

A trio of dashing military types, amply plumed and cloaked, strike bravado poses at the far right.

Even Jews might crash the party in the park but they could not count on a warm welcome. On 13 May 1619, four young Jewish men from eminent Ghetto families were apprehended by the police at the Porta al Prato (on the threshold of the Cascine):

Gratiadio son of Lelio Blanis, Agnolo son of Teseo, Benedetto son of Lione and Danilo son of Elia, all Jews, were arrested by a constable ...outside the Porta al Prato. They were returning from the Cascine, where they walked along the avenue playing a tiorba [a kind of large lute]...allegedly violating the ban against setting foot in that place. The accused all confessed that they were indeed returning by way of the avenue since they had seen many other people walking there and were unaware of the prohibition.

This was a blatant case of police entrapment, far fom rare in the Florence of that day.

The Magistrates considered affidavits attesting that the accused were all under fifteen years of age. They also considered the testimony of a witness who swore that these Jews were incited to go to the Cascine in the first place by the constables themselves, who encountered them in the tavern at Ponte alle Mosse [on the inland edge of the Cascine] and told them that there was a big dance going on. The Magistrates therefore decided to absolve the Jews since they were just boys and they had no intention of breaking the law—and in fact, they were not engaged in anything illegal.

[For a fuller discussion including the archival sources, see Edward Goldberg, Jews and Magic in Medici Florence (University of Toronto Press, 2011), pp.140-41.]

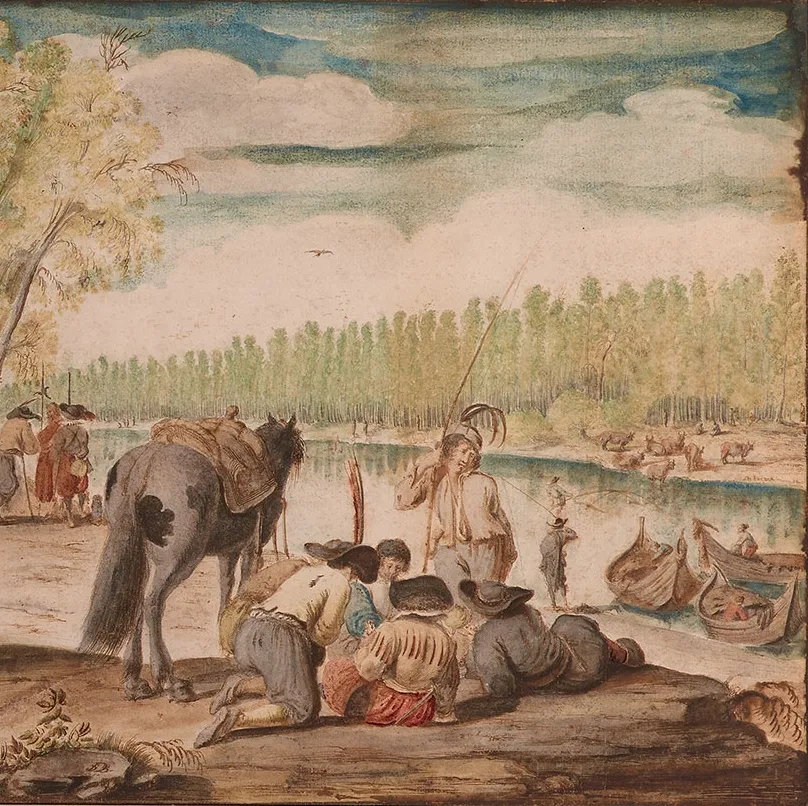

Here in the Grand Avenue—where Gratiadio, Agnolo, Benedetto and Danilo strolled and strummed—a knot of spectators watch a game of pallamaglio (from palla = ball and maglio = hammer).

This ancestor of croquet was a highy exclusive pastime since long, straight, level alleys existed only in aristocratic pleasure grounds. To the left, a man with a wooden mallet drives a wooden ball toward a distant target, while on the right a child develops these skills.

.webp)

A watercolor by Adriaen van de Venne (c.1620-26) shows a game of pallamaglio (pall mall in English) in a similar alley, perhaps in the Hague (British Museum). The featured players are Frederick V (Elector of the Palatinate) and Frederick Henry (Prince of Orange and steward of of the Northern Netherlands).

In the center, a party of youthful gamblers play cards. Toward the right, one fisherman casts his line from the riverbank while another wades into the middle. Across the way, cows and cowherds—or maybe just cows and picnickers—form a pastoral group.

In the Cascine today, we still encounter cows and dairy production at every turn—at one or two removes, when we look into the past. We can begin with the place name. "Le Cascine" means "The Cheeseworks" (plural), from "cascio", an archaic word for "cheese".

Even the mythic Prato del Quercione began its sporting history as a pasture. The Fontana delle Boccacce del Quercione (Fountain of the Funny Mouths at the Great Oak), with its five whimsical spouts, provided water for the Grand Duke's cows grazing picuresquely on that lush terrain.

In the Cascine, it is not always easy to tell where infrastructure ends and fantastic embellishment begins.

In 1796, after constructing his bovine watering station, architect Giuseppe Manetti realized the nearby Ghiacciaia delle Cascine—ice house and Egyptian Pyramid. The Ghiacciaia did indeed supply ghiaccio (ice) during the hot summer months, chilling wine and freezing sorbets for dallying courtiers—while channeling the eternal allure of the Ancient East, with a nod to fashionable Freemasonry.

As the Eighteenth Century shifted to the Nineteenth, the character of the Cascine evolved slowly but decisively—taking the form of a modern public park. Enlightened principles played a role, but so did evolving tastes. Hunting ceased to define aristocratic identity in the old way while other sports emerged.

Meanwhile at the Tuscan Court, the emphasis in dairy production shifted from cheese to butter. The House of Lorraine, which succeeded the Medici, was essentially Austrian—with a northern predilection for butter-based cooking and baking.

It wasn't difficult for the Lorenesi to free up the broad pastures of the Cascine. Butter-making has a quicker turn-around time than cheese-making, which encouraged decentralized small-scale production. Burraie (butterworks, from burro=butter) proliferated in the hills around Florence. Small herds lived and grazed on site and their milk was processed on a daily basis, in cool below-ground facilities.

The Age of Enlightenment loved model farms that espoused the latest scientific techniques, also agricultural academies, colleges and the like. Various institutes of this sort cycled through the Cascine over the years, splitting and amalgamating, moving away elsewhere and sometimes moving back.

The Palazzina only became part of the University of Florence in 1936, under the auspices of the Mussolini regime. Along the way, it hosted a private agricultural school for young ladies of the land-owning class, a forestry institute and a fashionable caffè-restaurant.

We make our way through the Cascine in its post-dairy phase, tracking back and forth between architectural relics scattered across the landscape—sporting curiosities for the most part.

Aerial view of the Cascine in 1931, showing the proliferation of sports facilities. The vast track in the center is the Ippodromo (Hippodrome, for horse racing). This view is from the archive of Enrico Pezzi, a Florentine pioneer of aerial photography.

At the upper left corner of the Ippodromo, we see a cluster of buildings including the Palazzina Reale and the Tiro a Segno (Target Shooting Club).

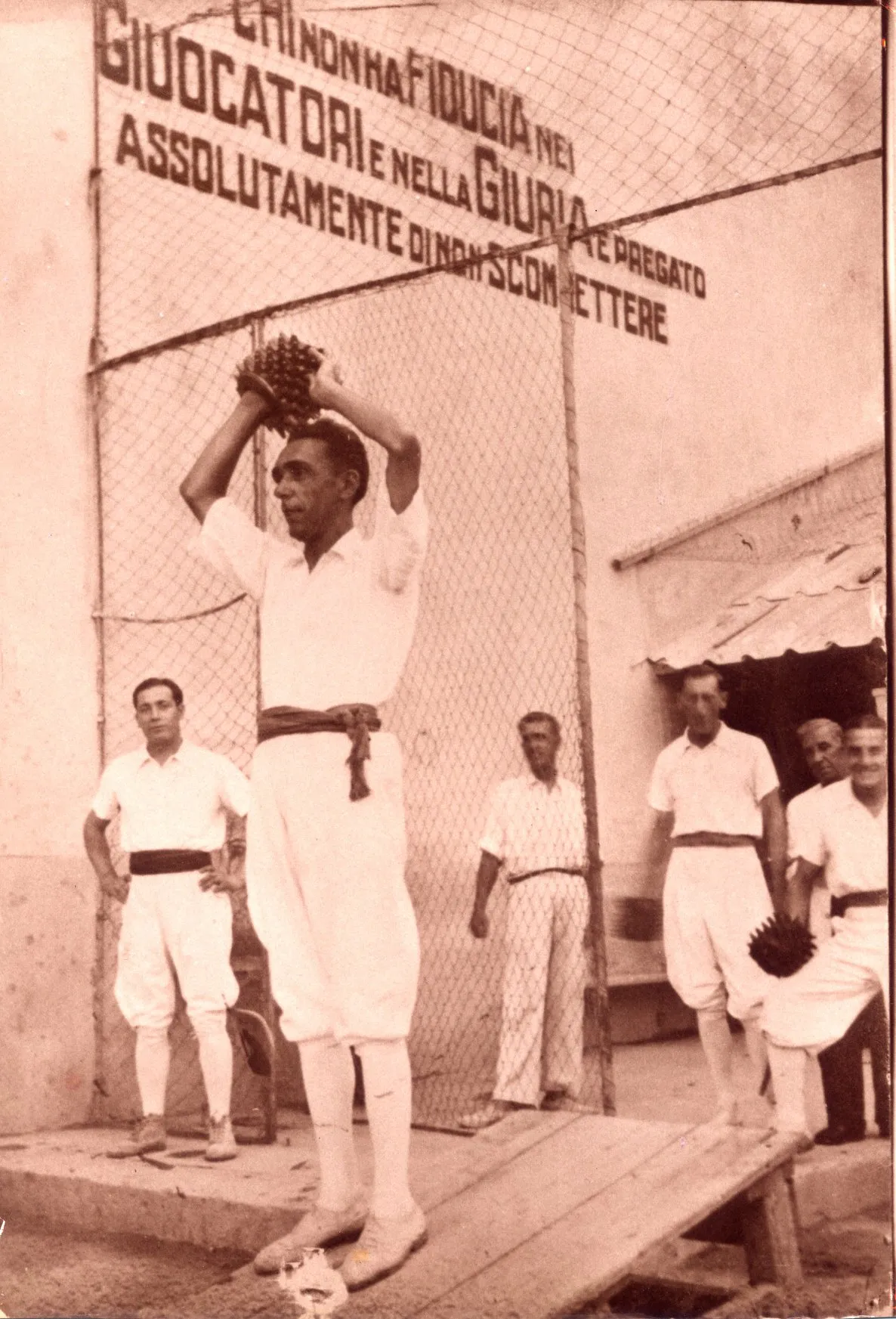

SFERISTERIO COMUNALE FIRENZE

The Florentine Municipal... what?

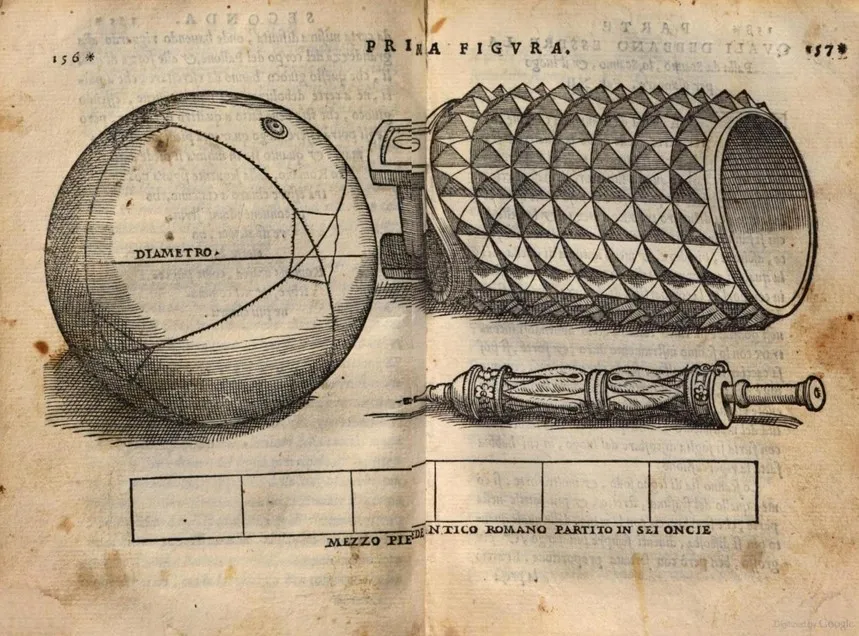

The Italian word sferisterio comes from the Latin sphaeristerium which in turn derives from the Greek sphairistérion. A sphairistésis a ball-player, from sphâira (ball)—the obvious English cognate being “sphere”.

So, a sferisterio/ sphaeristerium/ sphairistérion is a place where ball-games are played—but not just any ball-games, to be sure.

Suddenly we arrive at the gateway to a parallel universe—for the fanciful among us—or at least, a quirky constellation of ball-games from way-back-when, with their own equipment, their own rules and their own cadres of passionate followers.

By the Sixteenth Century, pallone al bracciale (ball with the armpiece) was already established as an elite sport. Still, it was only one of various popular ball games, then and even now. To this day, the Sferisterio Comunale in the Cascine hosts—few but enthusiastic—practitioners of pallone al tamburello (drumhead ball), tamburello a muro (drumhead ball against the wall) and pallapugno (fistball), as well as the familiar pallone al bracciale (ball with the armpiece).

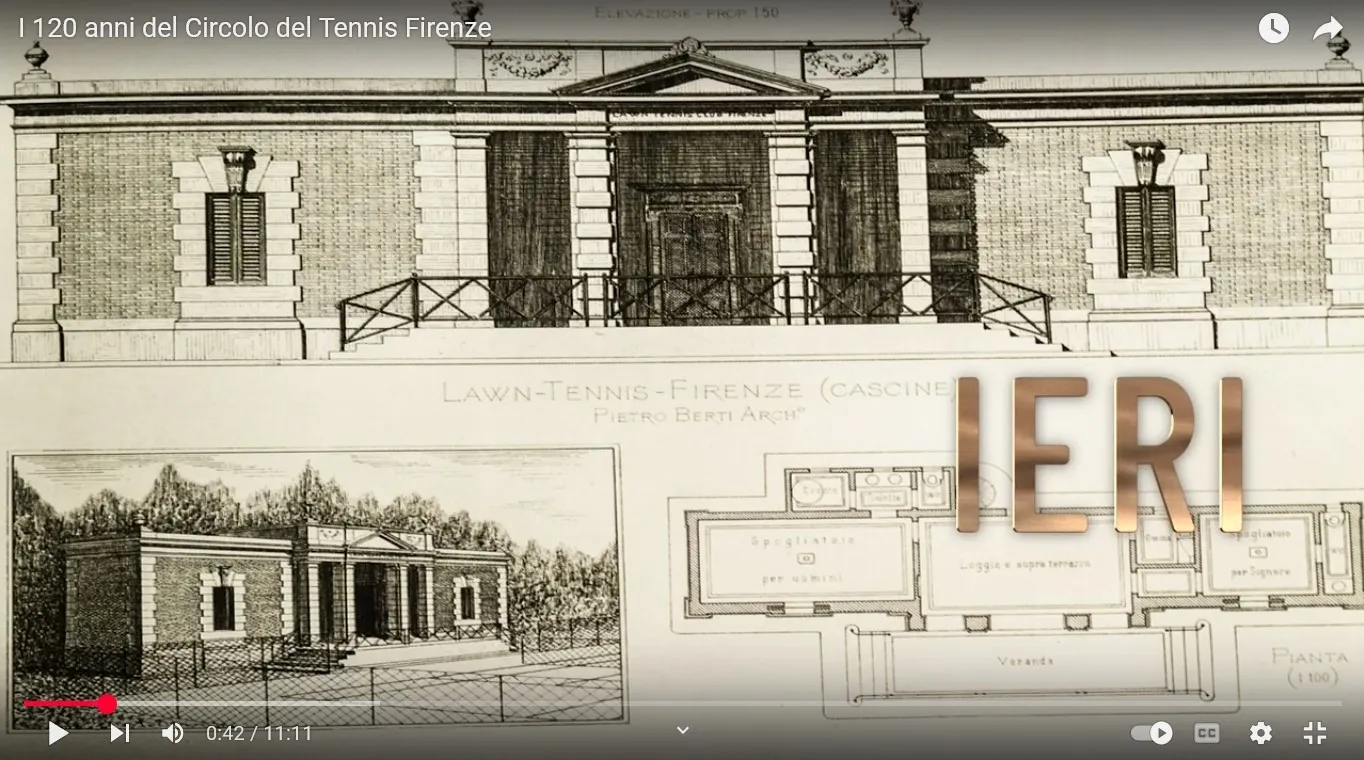

The Cascine also hosts ball-games of a less esoteric kind, especially at the Circolo del Tennis di Firenze, one of the top-ranked clubs in Italy. Tennis—like bracciale, tamburello and the rest—began as an exclusive pastime but gradually made its way into the mainstream of popular sport.

The Circolo del Tennis Firenze was founded in 1898 to promote lawn tennis in the English style (which was already played at a few private villas). The organization soon shifted to clay courts after Vittorio Cosimo Cini—a sensationally wealthy Tuscan industrialist and the club's first president—built an elegant facility, at his own expense, in 1900.

The Circolo del Tennis soon emerged as a pioneering institution, while maintaining its air of aristocratic calm.

In 1902, the Circolo del Tennis Firenze became the first Italian club to schedule regular competitions for women. Then in 1910, the twelve preeminent national associations met there to found the Federazione Italiana Tennis (Italian Tennis Federation).

Horse races were first documented in Florence in 1827 at the all-purpose Prato del Quercione, organized more or less spontaneously by English gentlemen of a sporting persuasion. In 1847, racing was shifted to its current location—the Ippodromo del Visarno, as it came to be known—with a varying program of flat racing, harness racing and steeplechase.

Until 1871, Florence hosted a royal court (with the Lorraine Grand Dukes of Tuscany, then the Savoy Kings of Italy). Meanwhile, there was the local aristocracy and gentry, plus a shifting array of more or less well-heeled foreigners. Still, it was never clear that Florence could support a full horse-racing calendar and the Ippodromo hovered on the edge of bankruptcy for much of its history, until it finally closed in 1931 (the year of the aerial photograph).

The Ippodomo was relaunched in 1939 with sleek new structures in the latest style and a capacity of 8,000. But then the Second World War intervened, with the social upheavals that folllowed—leaving old-style horse-racing out in the cold.

There were desultory attempts at repurposing the Ippodromo del Visarno—as a generic event space with a few occasional horses on the side.

.jpeg)

The Ippodromo's extensive stabling, training and residential facilities were then besides the point—except for those few who valued such traditions.

Still, the old dream of equestrian glamor dies hard, especially in the Never-Never-Land of present-day Florence. This is a medium-sized town with a mythic past and a sporadically glitzy present, battered by wave after wave of inscrutable VIP events.

Stuff happens...but why? It is easy to suspend disbelief when you have Brunelleschi's Dome and Giotto's Bell Tower off on the horizon, shimmering in the summer heat.

Case in point:

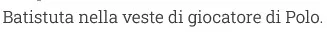

"Cavalleria Toscana Polo Challenge, a charity event...On 18 June 2009, starting at 6pm, at the Ippodromo del Visarno in the Cascine..." (Cavalleria Toscana is a sportswear brand that features equestrian and equestrian-themed fashion.)

In fact, they buried the lead: "for an exclusive appearance of Gabriel Batistuta as a Polo Player".

There would have been a collective gasp from one side of the Tuscan Capital to the other, if anyone saw the announcement. (Fortunately, my brother happened upon it in a sports blog.)

This...I mean to say...was Gabriel Batistuta...!!! The loved then despised then grudgingly loved again (speaking in 2025) icon of the Florentine football team.

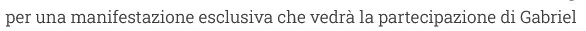

GABRIEL OMAR BATISTUTA doing his "mitraglia" (machine gun) thing, as was his wont, when he scored...often. From 1991 to 2000, this Argentine striker was the most dynamic and charismatic figure on the Fiorentina football team, making 269 appearances and racking up 168 goals.

a.k.a. BATIGOL ("hit the goal")

a.k.a. EL ÁNGEL GABRIEL ("the Angel Gabriel", referencing his name)

a.ka. EL RÈ LEONE ("the Lion King", for his flowing blond hair)

So what...anyway...was the deal on June 18, 2009?

Were we simply going to turn up at the Ippodromo del Visarno and wander in—without even a hint of a ticket or invitation?

Then... lo and behold!... the FIORENTINA LEGEND would materialize ...before our dazzled eyes?

So we did, then he did and here are the photos to prove it. But what on earth was really going on?

The Ippodromo holds 8,000 spectators and at least 7,950 seats were left staring into space.

The organizers had rigged a notional public event—entirely for "image", it would seem.

No actual "public" was required, which was a damned good thing.

This Argentine magazine was promoting "the Polo Lifestyle” with BATIGOL as BATIPOLO leading the charge. The retired football star must have been heading to the airport on his way to Florence when the rebranding campaign broke.

Back in his home-town of Reconquista (Province of Santa Fé), Gabriel Batistuta recently launched a new polo team: LA GLORIA—fulfilling a boyhood dream while reshuffling the cards, since his career on the football field had reached its natural end. (In 2009, he was 40 years-old and he had stopped playing in 2004.)

The June 18 event in the Ippodromo del Visarno was only one of many such—all "fabulous", of course—in and around that summer’s edition of Pitti Uomo (June 16-19), Florence’s biannual men’s fashion week.

On a background of Fiorentina purple ("viola"), we see (upper left) the Florentine lily ("giglio") with a polo mallet poking out, (below) LA GLORIA, the name of his new team. The logo and slogan, "LA DOLFINA Polo Lifestyle" (in English) appears at the upper right. LA DOLFINA was already a top Argentine polo franchise and a marketing juggernaut. (Were they promoting LA GLORIA as a LA DOLFINA farm team?)

BATIPOLO was playing the Fiorentina card for everything it was worth and a good deal more, appropriating both the team's color and its chief symbol. At that very moment—while the signature event in the Ippodromo del Visarno played out—he was floating various and sundry polo-related ventures, all with an essential Florentine component.

Not least was a massive project in the Mugello district northeast of Florence, the ancestral homeland of the Medici. In 2009, Alfredo Lowenstein—an Argentine hotel magnate and real estate developer—completed the acquisition of Cafaggiolo, their chief dynastic property. (Genealogists still know them as the Medici di Cafaggiolo.) Lowenstein's plan was "to turn the Renaissance palace into a high quality super resort" (to quote a brochure). This included several polo fields and a solid slam of "The Polo Lifestyle".

There was a problem, however. In 2009, Florence's love affair with Gabriel Batistuta was going through a notably rough patch. After he bailed on Fiorentina in 2000, he made the round of richer clubs—going from Roma to Inter Milan to Al-Arabi (Qatar)—scooping up fat paychecks along the way. His finest moment, most would agree, was not shilling for Qatar's outrageous, unconscionable and ultimately successful World Cup bid.

Leaving BATIPOLO aside, he had a new nickname in Florence to add to the already long list: IL MERCENARIO (The Mercenary). Thousands of local fans had watched in shock and dismay while EL ÁNGEL GABRIEL morphed into poster boy for the corporate greed of Il Calcio Moderno.

But still—for a magic moment—the Ippodromo del Visarno came back to life, if you didn't look too closely. Even gate-crashers like us might pretend that it wasn't a gloriously bogus occasion, this equestrian photo op with a free-range cocktail party thrown in.

The years pass—from 2009 until more or less today.

Work on the Cafaggiolo project progresses at a glacial pace, but it progresses—which is saying a lot in Italy, when there is a major historic property and several municipal jurisdictions in the mix.

The Lowensteins turned a breathtaking trick, rerouting a public road—thereby amassing three contiguous polo fields.

But where is BATIPOLO? We don't see him in that historic photo, nor is there any trace of the LA GLORIA club back in Argentina after 2017.

But in the parallel universe of Florentine Football, time and selective memory kicked in—proving that even the most prodigal golden boys can go home again.

In 2014, Gabriel Batistuta joined the Viola Hall of Fame, welcomed by the almost equally mythic Giancarlo Antognoni. That was 14 years after he left the team—scarcely lightening speed—and 9 years after he stopped playing (although he continued to coach the Argentine National Team).

The same years passed at the Ippodromo del Visarno, which sunk into ever deepening decay —managed by a contractor who was either an incompetent rogue or a much-maligned victim of the Florentine administration. In any case, they generated more recrimination than solutions and no few lawsuits.

But still, a persistent few devoted themselves to saving the Ippodromo for horses and a quiet majority—in the city and in City Hall—seemingly liked the idea. First, there was an equiphile renaming in the spring of 2023, then a political slug-fest during the autumn and winter of 2024-25.

“An indecent and unacceptable situation!” emphasized Dario Danti, Assessor of Public Property.

“The situation is beyond alarming!” stated Caterina Biti, Assessor for the Quality of Urban Life. "This period structure, of notable beauty, is falling to pieces.”

Supported by a team of technical experts, The two Assessors then ordered the contractor to file a detailed plan for bringing the Ippodromo up to standard (deadline December 13, 2024).

And now time will tell…

(11) "GO THROW MYSELF OFF THE INDIAN"

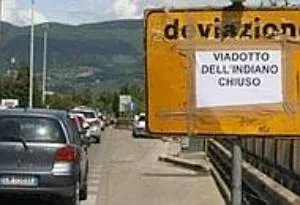

Say “L'INDIANO” to everyday Florentines and nine out of ten assume that you are talking about an infamous highway overpass—known for soul-destroying traffic jams and bizarre outbursts of road rage.

This sign cues an old Florentine joke, "The Indiano is closed to traffic today!" "Oh good, nothing has changed!"

Inaugurated in 1978 and briefly hailed as a triumph of modern design and technology, the Bridge of the Indian was soon reimagined by locals as Florence’s nearest approximation to the Gates of Hell, inextricably associated with the worst moments of daily life—if you are a commuter, at least.

"Mi butto dall'Indiano" (or "mi butterò dall'Indiano", "vado a buttarmi dall'Indiano"...or a host of variants) all mean the same thing, "I am going to throw myself off the Indian". Usually this is accompanied by a laugh and a gesture of comic desperation—but joking aside, there has been a notable body-count over the years.

As for the remaining 10% of Florentines—mostly non-drivers, we can guess—"L'Indiano" conjures either the orientalizing cenotaph on the left or the Italianate pavillion on the right (in the photo, we see it in the final stages of its latest restoration).

In 1871—a year after the cremation of the Maharajah and three years before the unveiling of his funerary monument—the Florentine administration built a customs station on the edge of what was then the new municipal tax boundaries. In 1878, a room in the Palazzina was ceded for use as a caffé, since this was a scenic spot and a natural destination for excursionists. Eventually, the entire building was made over to social and recreational activities, hosting a succession of tea-rooms, bars, art clubs, art galleries and (on occasion) dens of counter-cultural reaction.

In fact, the best-known cultural franchise of this name was in the center of town, not the farthest reaches of the Cascine. By the early post-war period, THE INDIAN had been established as an instantly recognizable brand embodying edginess of every sort.

The chief oddity of this little corner of Florence is its nowhere-and-everywhere quality.

It can look like just about anything, depending on your vantage point, your camera angle and your editing skill.

Rustic paradise? Exotic sanctuary? Exurban hellscape? Take your pick!

The Indian is one of those places where stuff accumulates, at the juncture of two rivers and various roads—beginning with the kharma of a young prince, prematurely deceased far from home.

The Indian and its environs exert a unique attraction—which most Florentines acknowledge with a nervous grin.

According to local lore, this is a place where unquiet souls go to merge with the ambient strangeness.

This is also a place where people go to end their lives, as even the most casual newspaper reader knows well.

"While on the Viaduct, he announces his intended suicide; the police dissuade him."

"The man telephoned law enforcement agencies saying that he wanted to throw himself off the Ponte all'Indiano in Florence. He was tracked down and then hospitalized at Careggi."

So, the police managed to "dissuade him". Can we pass this off as a good-news story? Not if we read past the headline and the lead.

"He telephoned law enforcement agencies and the press rooms of various newspapers, announcing his intended suicide, 'I'll throw myself off the Bridge at the Indian' (mi butto dal Ponte all'Indiano)."

"The man—a 50 year-old unemployed Italian paraplegic—was tracked down by police patrols and stopped before committing that extreme act. They intervened at around 3pm on the pedestrian walkway under the bridge."

"He was transported to the Hospital at Careggi, where he was admitted under medical observation."

Then the backstory...

"As reconstructed by the agents, the man presented himself in Palazzo Vecchio—CIty Hall—in order to discuss his employment problems with a member of the town council whom he had previously contacted by e-mail. However, the meeting failed to resolve his difficulties in finding work. At that stage, he proposed taking his own life. 'I'm not able to work, the institutions don't help me, and the subsidy allocated to me is insufficient', the 50 year-old informed the agents who saved him."

So, the tale ended right there—with a "rescued" paraplegic tucked up in a hospital bed? Not hardly, but we don't have the man's name and are unlikely to learn more (although he was dispatching e-mails and maybe texts).

Meanwhile, many skip the cry for help and cut straight to the extreme act.

"A Woman Commits Suicide By Throwing Herself Off The Viaduct of The Indian. A woman is dead after throwing herself from Viaduct of the Indian. The 46 year-old died on board the ambulance while being transported to the hospital."

"Elderly Man Falls From The Viaduct Of The Indian." "A man, ninety years of age, is dead late this afternoon after falling from the Viaduct of the Indian. The National Police and the Emergency Services intervened on the spot. This was ascertained to be a suicide. The man was suffering from a serious illness."

Many long sad stories end at the Indiano and are then filed away as brief (usually anonymous) newspaper reports—protecting "privacy" but making the tragedy strangely unreal and leaving a host of unanswered questions.

How...for example...did the paraplegic 50 year-old and the seriously ill 90 year-old make their way unnoticed and evidently unaided to the aerial footpath, then (in one case) past the railing?

The bodies that collect at the Bridge at the Indian are not all suicides—at least, not quite. This is one of those fatal places where people without options go, less for a sudden release then to let nature take its course.

The nameless woman who expired on a trash-strewn river bank on a cold winter night remains a cipher in the pages of La Nazione. Florence, however, is a reasonably efficient city in a modern country with effective (if not perfect) public healthcare.

The 40 year-old (no longer young but certainly not aged) was firmly embedded in the system and she was receiving advanced medical treatment (dialysis no less). At the Hospitals of Careggi and Santa Maria Nuova, she was popping up on someone's screen. Meanwhile, she had a "compagno" (male companion) who sounded the alarm—when and how, we wonder?

"This afternoon, the cadaver of an Asiatic man came to light in the area of Cavallaccio, in the isolated terrain between the Bridge at the Indian and the Florence-Pisa-Livorno highway. In the course of their duties, local sanitation workers noticed the corpse and immediately called for assistance."

"The identity of the individual and the cause of death are still unknown: there are no indications of violence, but the position of the shoeless body—lying on its back with arms extended, does not exclude the possibility that it was brought there from some other place."

"The police investigating the case arrived immediately along with the public official Ester Nocera. The area was closed off, with repercussions for traffic on the Viaduct."

Who was the deceased and where did he come from? "Asiatic" covers no small swathe of the globe. In any case, we can assume that a grand cremation and a marble monument were not in the offing. In fact, Florence being Florence and human nature being human nature, the rush-hour traffic obstruction was probably noticed most.

Let's imagine (idly or not) that the young Maharajah never died in Florence, with the ensuing pomp. The bridge would still have been built, since highway development has an uncanny logic of its own. Then the usual unfortunates would have found their way—through the the social safety net and over its side.

Or at least some—since only The Indian is The Indian, when the time comes. "I am throwing myself off the Isolotto-Peretola Viaduct" simply doesn't do the job. Where is the mythic power, the cosmic fatality, the gravitational pull?

(12) THE INDIAN COMES HOME

Or rather, home comes for the Indian?

Not a package of cut-rate incense, notwithstanding the evident influence of that sort of art. Rather, this is "Florence's Indian: The Story of Rajaram Chuttraputti and his Temple in the Park of the Cascine".

Over the years, the Indiano amassed a fervent coterie, among Florentines in search of an easy dose of exotic culture in a resolutely unexotic city. (You still have your work cut out for you, finding an even just-okay Indian—or Chinese, Thai or Vietnamese meal. My local subcontinental life-saver was the surprisingly good Al Noor in Borgo La Croce.)

Richi Shah from Mumbai, a designated "Cultural Brand Ambassador of India", shares unique insights from her brief but totally mellow visit to Florence. ("Kinda one of our best days in Italy!...best vibe ever!...cute little wine windows!...eat as much gelato as you can!...interesting, right?")

India is a very big country which—suddenly, in recent years—emerged as a massive international tourist presence. There is seemingly no place in the world where you don't encounter numbers of them, usually pleasant and well-mannered, often in distinctive multi-generational family groups. Now they even have their own gang of roving influencers.

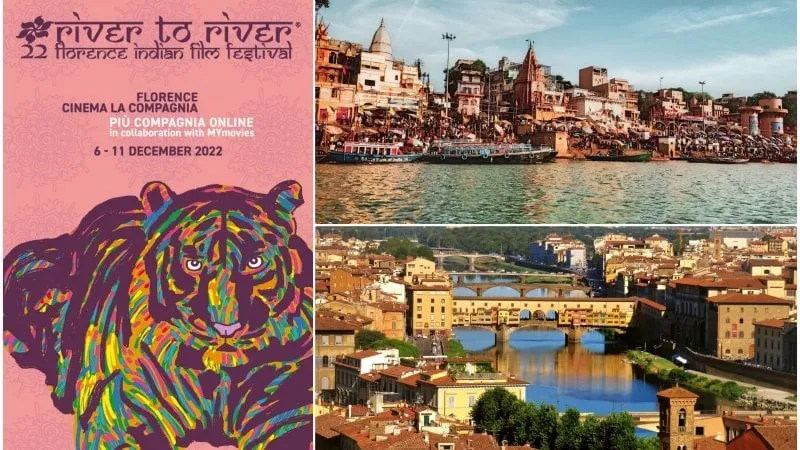

For several decades now, there has been an annual Florence Indian Film Festival.

Also a thriving sector of event planners for the burgeoning Indian market.

Where does Florence's formerly lone Indian fit into this expansive new picture?

A century-and-a-half flowed by at the juncture of the two rivers, at the outermost edge of the Park of the Cascine.

Back in Kohlapoor, the Seventh Maharajah was never quite forgotten—especially now that Florence has become a recognized brand in India too.

It is not easy for non-specialists to sort out Chhatrapati genealogy. Then there are the endlessly complicated relations between family members today. Judging from the English-language Indian newspapers that I could access online, virtually everyone is involved in politics and the trio in the above photo are not always allies.

"Member of Parliament ...Brand Ambassador, Maharashtra State Tourism and Heritage Development Corporation ...Trustee of 14 different trusts run by the Kolhapur Chhatrapati Family... He has a deep and abiding interest in the restoration of forts and historical monuments with an aim to promote Indian heritage and tourism ...Chief Guest of Honour at the Royal Heritage Luxury Show in Dubai."

This ceremony at the Monument to the Indian—in the shadow of the notorious bridge of that name—was both an ancient and a modern occurrence, whatever was going on and why.

A century-and-a-half has passed since the mysterious late-night cremation, when Florentines piled into their carriages to see a barely imaginable sight.

And now we've accompanied the once-young maharajah's descendants all the way to the Indian. When you reach the edge of the earth, where do you go next?

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.