THE SORDEVOLO PASSION: Jewish Infamy Takes Center Stage in the Foothills of the Alps

CONTENTS:

(1) CHRIST-KILLERS, THEN AND NOW

(2) BEFORE YOUR VERY EYES

(3) CURTAIN CALLS

(4) UPDATES

(1) CHRIST-KILLERS, THEN AND NOW

When did it stop being alright to hate Jews—and more specifically, despise them as the accursed murderers of Christ?

For Catholics, at least, the answer should be easy:

28 OCTOBER 1965

On that date, nearly fifty years ago, Pope John XXIII issued the edict Nostra aetate (In Our Time)—rejecting the ancient assumption that the Jewish people tortured and crucified Jesus Christ.

In the years that followed, the Church took further steps—slowly and hesitantly but generally moving in the right direction—managing their own collective guilt for many centuries of Jewish suffering.

No one will forget Pope John Paul II's visit to the Great Synagogue of Rome on 13 April 1986, when he embraced Chief Rabbi Elio Toaff. No one will forget the Pope's moving statement at that time:

“With Judaism, we have a relationship which we do not have with any other religion. You are our dearly beloved brothers, and in a certain way, it could be said that you are our elder brothers.”

But Church teaching is one thing. Custom and culture is another.

Case in point:

LA PASSIONE DI SORDEVOLO

Every five years since 1815, the inhabitants of the tiny Piedmontese town of Sordevolo (current population 1,300) have staged an imposing recreation of the last days of Christ— as it was long imagined by Catholic believers.

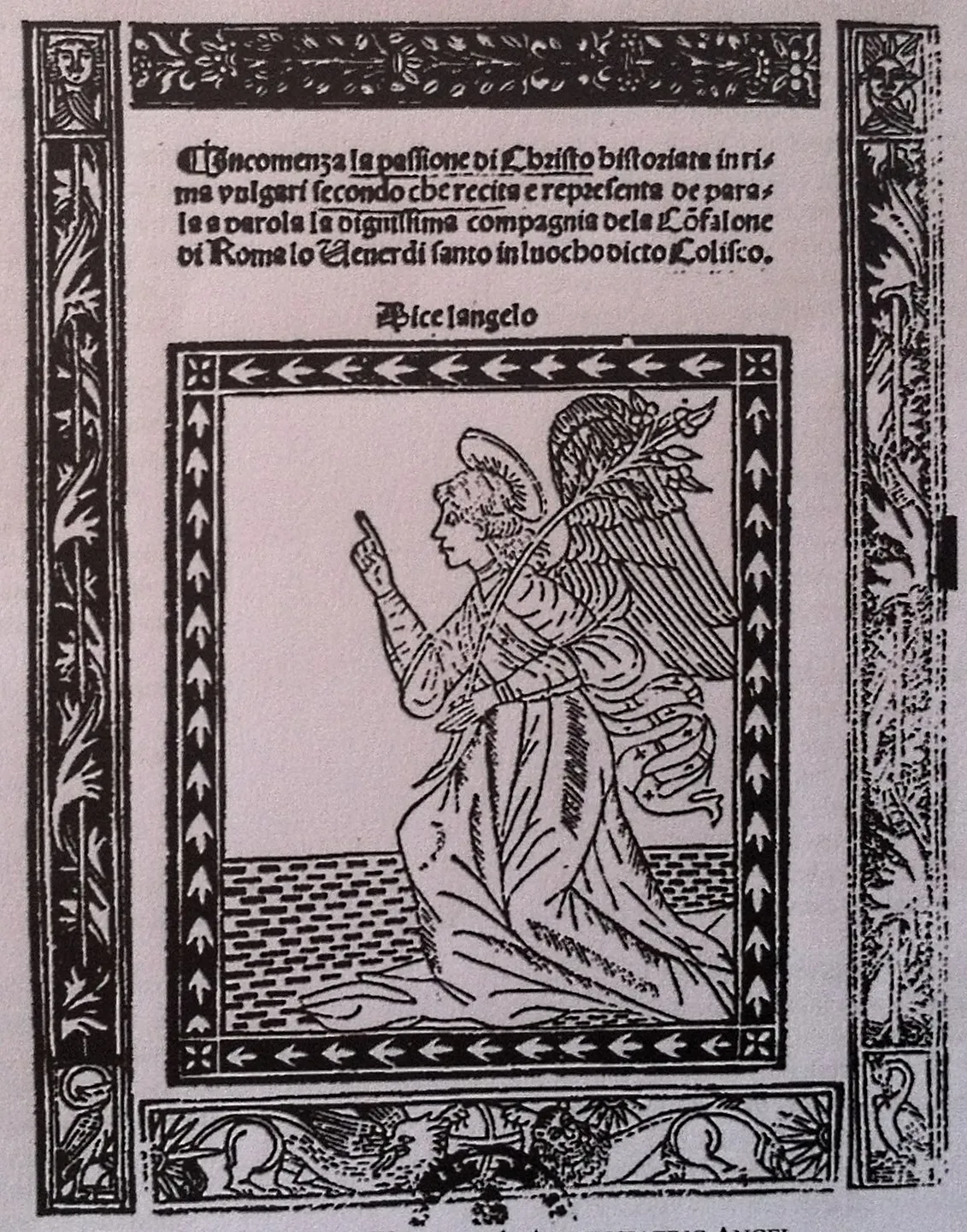

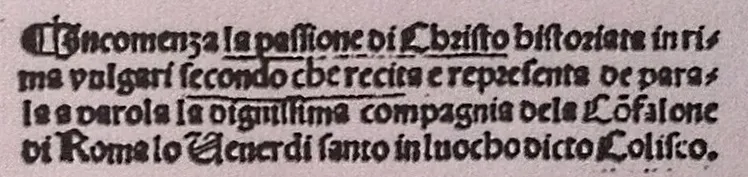

The historical roots of this particular Passion play go deep. The Sordevolesi are reciting a five-hundred year-old text that was staged in the Colosseum in Rome on Good Friday from circa 1490 until 1539—giving epic expression to the Jew-hatred of a seemingly remote time.

Giuliano Dati, a Florentine cleric, wrote this play and first published it in Rome around 1496.

That was then...

It is also now.

(2) BEFORE YOUR VERY EYES

How do we describe the cumulative effect of hour after hour of rhyming verse in colloquial quattrocento Tuscan—now overlaid with upland Piedmontese? Still, we are witnessing an amazing show...

No one can doubt the dedication of the participants and their pride in sharing something meaningful with the world.

The Sordevolo Passion is not only an extraordinary historical survival. It is a defining feature of local life and a labor of love—representing a massive investment of time, energy and resources.

But 1490 was then and this is now...

The literary and theatrical forms are antique, but so is the content—taking us back to a time when despising Jews was an essential element of both public and private life.

What if the spectator today is both a Jew and a historian? You find yourself watching the play with two sets of eyes.

While admiring the intricacies of a rare and valuable historical artifact, you feel your mind seizing up and shutting down —like an overheated computer.

Is THAT actually happening HERE and NOW?

Are those comic-book yids really grimacing and waving their arms —right in your face?

And those other fancifully-dressed oddities —are they actually screaming the anti-Jewish imprecations you seem to hear?

According to Catholic theology, God willed His Son's death and resurrection.

So the relentless mechanism of the Passion— compellingly expressed by Giuliano Dati —was all part of a Divine Plan.

But none of the horrors inflicted on Christ —betrayal, torture and crucifixion —could have occurred without Jewish scheming at every turn.

Nor would the story have made theatrical sense —in the Colosseum in Rome five-hundred years ago or in the amphitheater in Sordevolo today.

The relationship between Judas and Christ —betrayer and betrayed —defines the drama. But the betrayal itself is an Israelite conspiracy and Judas himself an archetypal Jew.

A Priest of the Temple counts out the infamous thirty pieces of silver.

Judas then earns his blood-money, taking the Jews to apprehend Jesus. They loathe Him as a rabble-rouser seeking to subvert Jewish Law.

The Jews cannot kill Jesus themselves, according to the letter of that very Law. So, they send Him off to their proxy—Pontius Pilate, Roman Governor of Judea.

Pontius Pilate defends Jesus' innocence —making a failed pitch for human compassion —but the Jews demand bloody retribution.

Pontius Pilate then seeks a compromise. According to custom, a condemned prisoner is liberated every year at Passover—but the Jews clamor for Barabbas' release and Jesus' death.

After the flagellation, Pontius Pilate makes a final plea for Jesus' life—vainly hoping that Jewish blood-lust has been sated.

Jesus is dragged to his death, under the watchful eye of the Jewish leaders.

Judas suffers remorse and seeks to return the thirty pieces of silver —but the Jews spurn him, now that he has done their will.

Then comes the familiar tableau on Golgotha.

Christ dies in agony, while His Jewish foes escalate their derision and abuse.

Three of them cast lots for His discarded garment. A gloating Pharisee wins.

Deposition...

Pietà...

Entombment...

Resurrection...

A relentless succession.

SPOILER ALERT: God triumphs and Jews lose.

(3) CURTAIN CALLS

But the show is far from over... For many, the essential part has only begun.

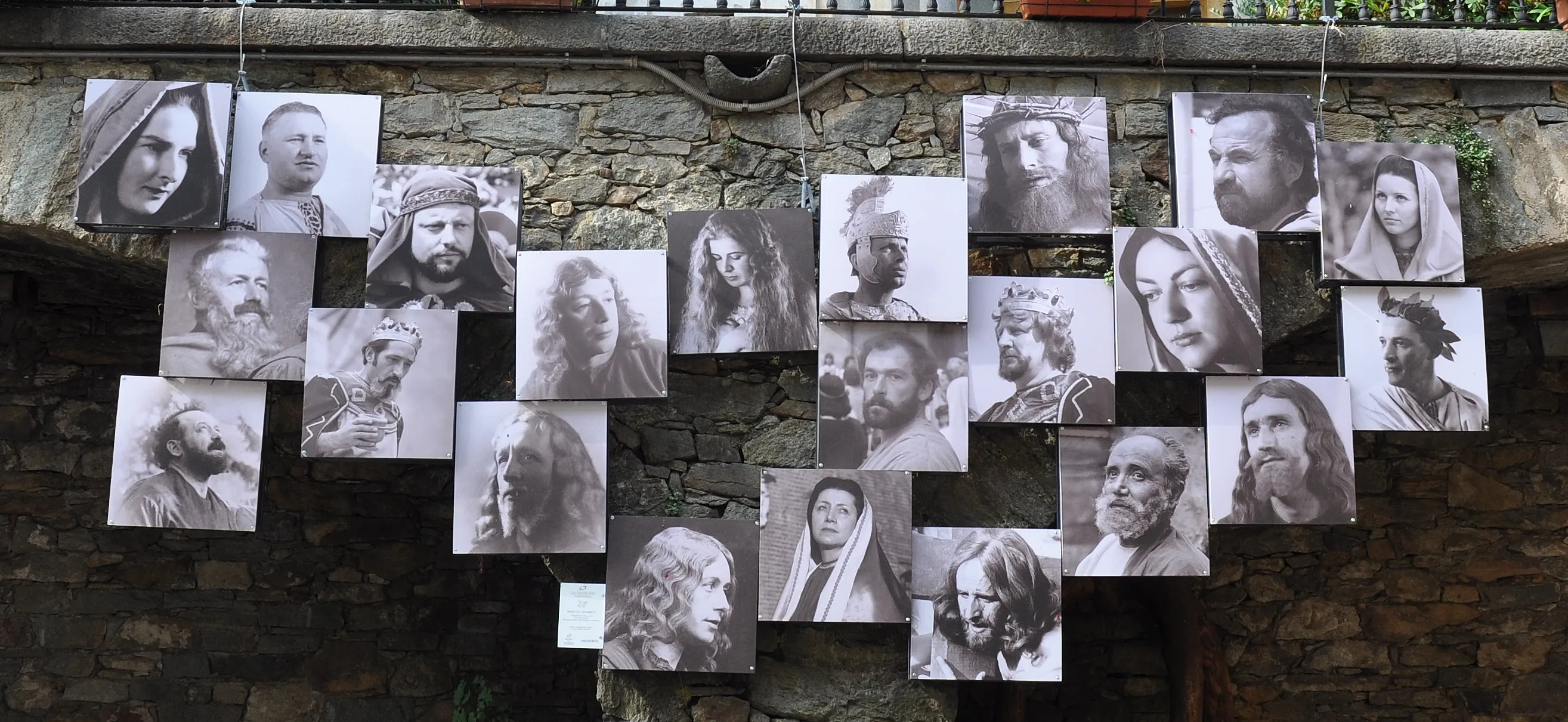

All four hundred cast members stream out to take their bows—to rapturous applause.

In full stage make-up. Including a battered but resilient Christ.

Jewish soldiers —also the kids next door —in vaguely Assyrian helmets and trousers.

And the wicked Pharisees—on a first-name basis with everyone in town.

Candle-carrying Jewish matrons —maybe lady Pharisees?— with men's prayer shawls too. Last seen in the supermarket or laundromat.

Then the audience floods the staging area. In an instant, ancient Jerusalem morphs into the local piazza.

In Italy, manifestazioni storiche —historic reenactments and the like —are things of their own. Especially in small towns. Whether they be battles on ancient bridges, medieval markets at local castles or football games in renaissance garb.

Almost always, we leave with the same impression: The locals are doing it for themselves and each other. The audience is certainly welcome but they are scarcely the main point.

In the world of Italian manifestazioni storiche, the Sordevolo Passion boasts an exceptional pedigree— produced more or less regularly over the course of two centuries.

In concrete terms, it represents a breathtaking achievement —demonstrating a level of local cohesion that is difficult to imagine in most parts of the world today.

But today being today, what about the Jewish aspect of the play— especially approaching the fiftieth anniversary of Nostra aetate and the two-hundredth anniversary of the Sordevolo Passion?

"It's in our DNA", the director of the Passion recently observed. And that is certainly true, since local families have been handing down dramatic roles and organizational tasks from generation to generation.

"Most Sordevolo residents know the text by heart", a featured actor noted. That is probably true as well— although memorizing verse after verse of quattrocento Florentine is no small task, even for a literary specialist.

For a long line of Sordevolesi, Giuliano Dati's vehemently anti-Jewish play has simply been "the play"— however alarming, objectionable and even bizarre it might appear to some, five centuries after its début in the Colosseum.

Historical texts, like Dati's Passion, are first and foremost historical texts. And works of art, like the Sordevolo reenactment, are first and foremost works of art. But meanwhile, as cultural historians are quick to note, "Context is everything".

The Sordevolo Passion is now entering its third century and rapidly developing an international following —with thousands of foreign visitors, especially from the United States. Questions are being asked that were never asked before, regarding the play’s meaning and intention.

In a few weeks, the 2015 season will come to an end, then— almost immediately —the people of Sordevolo will begin preparing the 2020 edition. Along the way, they can address these emerging issues —helping all of us see their Passion as they want it to be seen.

For the two quotes in the last section of this piece, see Elisabetta Povoledo, "Staging Passion Play for 200 Years, Italians Become More Than Merely Players", New York Times, 08/05/2015

(4) UPDATES

FIRST UPDATE (2015)

I first published the above post (on a different website) in the summer of 2015, while the 200th Anniversary Season of the Sordevolo Passion was still under way. I concluded in a somewhat breathless tone, suspending judgement and hoping for... I am not quite sure what.

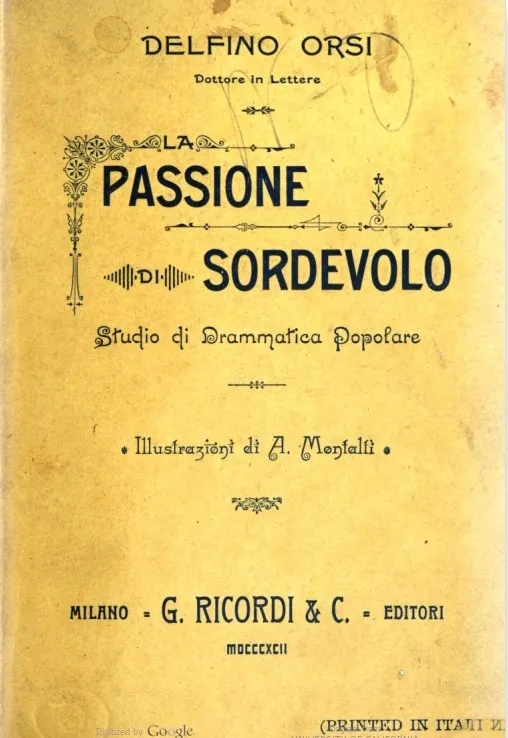

Between then and now, I completed the manuscript of my (unpublished) book, Carnival Blood, which I describe more fully elsewhere on this website. Along the way, I did a deeper dive into Giuliano Dati's Passione di Cristo over the centuries, which came to fill two chapters:

Chapter Five: The Passion of Christ (Rome)

Chapter Six: The Passion of Christ (Sordevolo)

I am an unabashed sentimentalist when it comes to local customs, especially in Italy and especially in small towns. That helped me get much wrong on the evening of August 28, 2015 —as I later learned.

"The Play" — I discovered —had not always been "The Play", a traditional artifact handed down from generation to generation, subject only to folkloric embellishment.

In fact, many defining local elements (including wild animals, uncanny spirits and scurrilous clowns) were suppressed during the early years of the Fascist regime.

The production then lapsed entirely from 1934 to 1950.

After the war, the Sordevolo Passion was reintroduced with a startlingly new profile:

The previously amorphous performance script was replaced by a relatively orthodox version of Giuliano's Dati's text, with far less room for improvisation.

The theme of Jewish malfeasance was pushed to the fore, no longer cushioned by an effusion of rustic whimsy.

"Modernizaton" and "mainstreaming" do not always represent moral progress—and the Passion of Christ is a case in point. In Carnival Blood, I save my personal opinions for the Sources section at the back of the book. In my comments on Chapter Six, I observe:

"I would be less concerned about historical expressions of Jew-hatred rising to the surface if it were not for the uncritical response in Italy and abroad, by representatives of the church, the media and the public."

Elisabetta Povoledo’s article in the New York Times on August 5, 2015 probably brought the Sordevolo Passion more publicity than it has enjoyed since its inception. Curiously enough, the word “Jew” does not appear even once in Povoledo’s treatment —revealing that she and I had experienced two essentially different plays.

I consider myself a somewhat conflicted fan of the Sordevolo Passion (and “manifestazioni storiche” —historical reenactments—in general). However, a number of developments need to be tracked.

The Sordevolo production is now being pitched to American pilgrims who often appear in organized groups, sometimes accompanied by their own priests —fully expecting to see (and feel) the Passion of Christ “as it really was”. I will never forget the wide-eyed assurance of a local we met, “You can reach out and touch Him. You’ll think you’re right there!”

Meanwhile, various Italian bishops have promoted the production (implying its doctrinal correctness) and ecclesiastical personages from Rome (with ideological and political axes to grind) have made well-publicized visits.

Jewish wickedness is an unmistakable element of the play’s message —a historical element that needs to be “contextualized” on the spot.

SECOND UPDATE (2022)

A lot has happened in the world snce 2015—not least the COVID pandemic. In Sordevolo, the 2020 edition of the Passion was postponed until 2022.

Meanwhile —largely due to COVID as well —I moved from Florence (where I had lived for several decades) to Washington DC (my nearly forgotten home town).

Since I have so many questions regarding the past and future of the Passion of Christ, I was sorry to miss this latest production. I will certainly do my best to check out the next one in 2027!

In the meantime, here are a few photos of the 2022 Passion, downloaded from the web. Has much or anything changed? There are many familiar costumes, sets and faces. But otherwise...who knows?

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.