WHOSE COLUMBUS? WHOSE COLUMBUS DAY? Part 2: The New Orleans Massacre (1891) and Italian-American Identity

(2) NEW ORLEANS 1891—AND AFTER

Nunzio Finelli did not live to see the début of an official Columbus Day holiday—which sputtered into existence on October 21, 1892 (not October 12), amidst the most horrendous of circumstances.

America has a long and terrible history of public lynching, usually in the South and most often—but not always—directed against African Americans.

The deadliest incident of this kind was the lynching in New Orleans of eleven ethnic Italians (seven of whom were in fact United States citizens) on March 15, 1891. The chain of events was was long and twisted, to say the least.

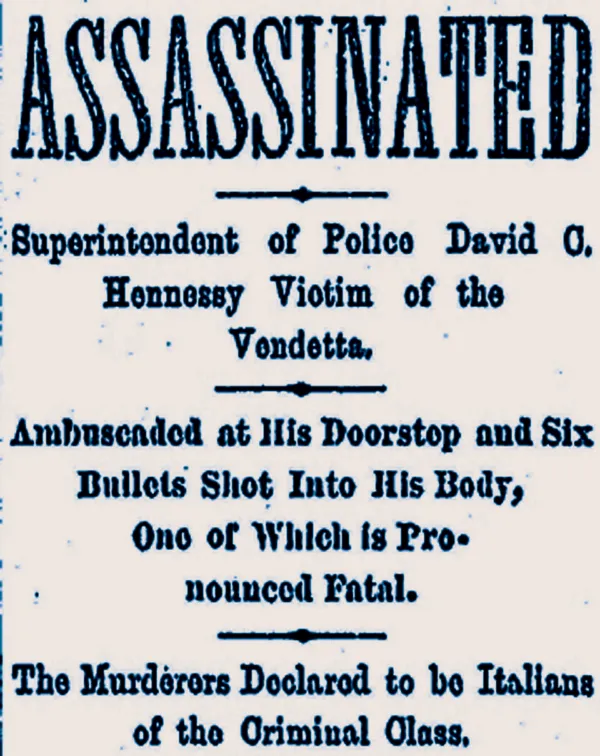

On October 15, 1890, New Orleans Police Chief David Hennessy was shot and killed near his home by unknown assailants. Since there were no reliable witnesses and too many motives, the backstory is as perplexing now as it was then—if you bother with facts, that is to say.

"Declared to be Italians of the Criminal Class." The Daily Picayune claimed omniscence, as did more or less everyone in town. "Victim of the Vendetta" was a particularly nice touch, implying that "the Vendetta" was a diagnosed condition, like " the cholera", "the measles" or "the Black Death".

Still, an Italian connection of some sort was not the worst guess. In New Orleans, the Provenzano and Matranga families were then struggling for control of various criminal enterprises.

As police chief, Hennessy was inevitably involved—whatever that might mean. Needless to say, rumors were flying fast and free that he favored one family over the other, while working an agenda of his own.

Then there were local politics and in late nineteenth-century New Orleans, honest brokers were few and far between. In his way, the current mayor Joseph Shakespeare was every bit as embattled as the Provenzanos and the Matrangas.

He represented a coalition of Republican-aligned factions that were struggling—against growing odds—to sustain their power and influence in a post-Reconstruction world.

The "Italian Population" excoriated in the Mascot's editorial cartoon was a new and startling phenomenon in New Orleans. Peasants, mostly Sicilian, began arriving in great numbers in the early 1880s, amidst the aftershocks of the Unification of Italy.

The new Kingdom had annexed the southern regions only in 1861, but it didn't take long for the regime to devastate their often fragile economies, while favoring the more developed North.

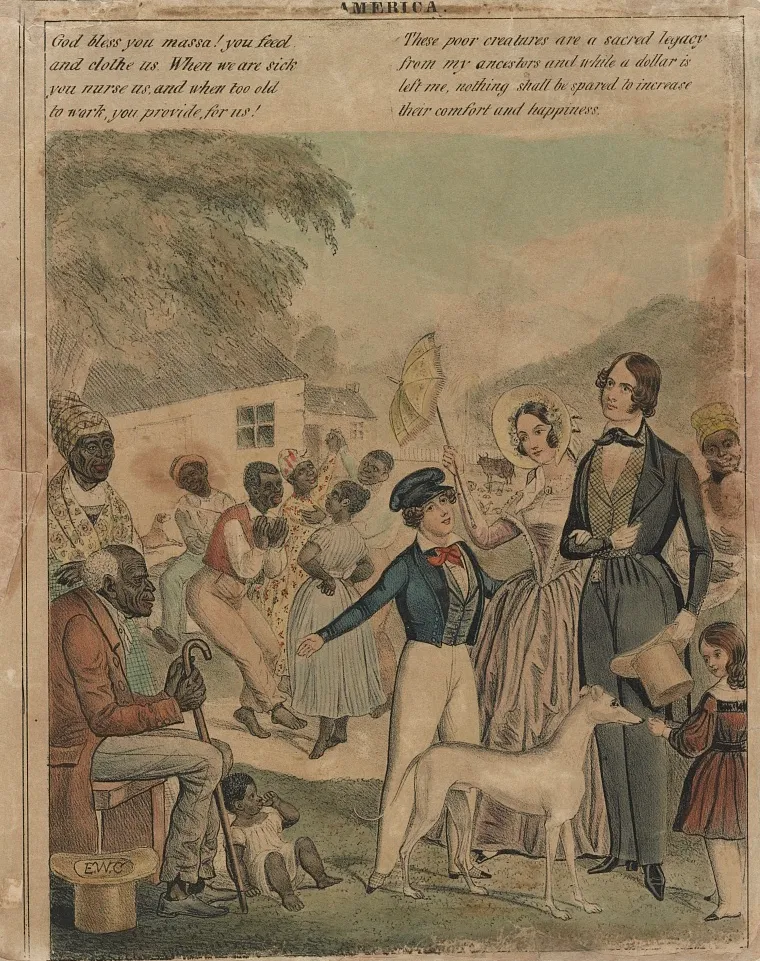

In Louisiana, meanwhile, freed slaves were abandoning their old jobs and heading elsewhere—creating a grave shortage of unskilled labor, especially on the docks and in the cane fields.

Enter the Italians. They were often scorned as "White Niggers", doing previously black work for much lower wages than native whites, while gravitating toward negro neighborhoods and negro society.

In broad economic terms, this seemed like a perfectly matched set of problems and solutions—substituting one mass of displaced workers with another. Economic principles, however, seldom have free reign—especially in the Deep South, where entrenched racial assumptions prevailed.

All Italians were of the Criminal Class—in the popular consciousness, at least—dictated by nature, with no questions asked. Meanwhile, politicians needed to rally support from an easily threatened white electorate, for whom loss of control was the ultimate evil.

Then there were local financial interests. Some of the more ambitious immigrants were moving into legitimate or semi-legitimate enterprises, servicing the port and managing food distribution.

Indiscriminate mass arrests of Italians followed the murder of David Hennessy and nineteen suspects were eventually indicted (a very mixed bag of good apples and bad, in so far as we can tell at this remove).

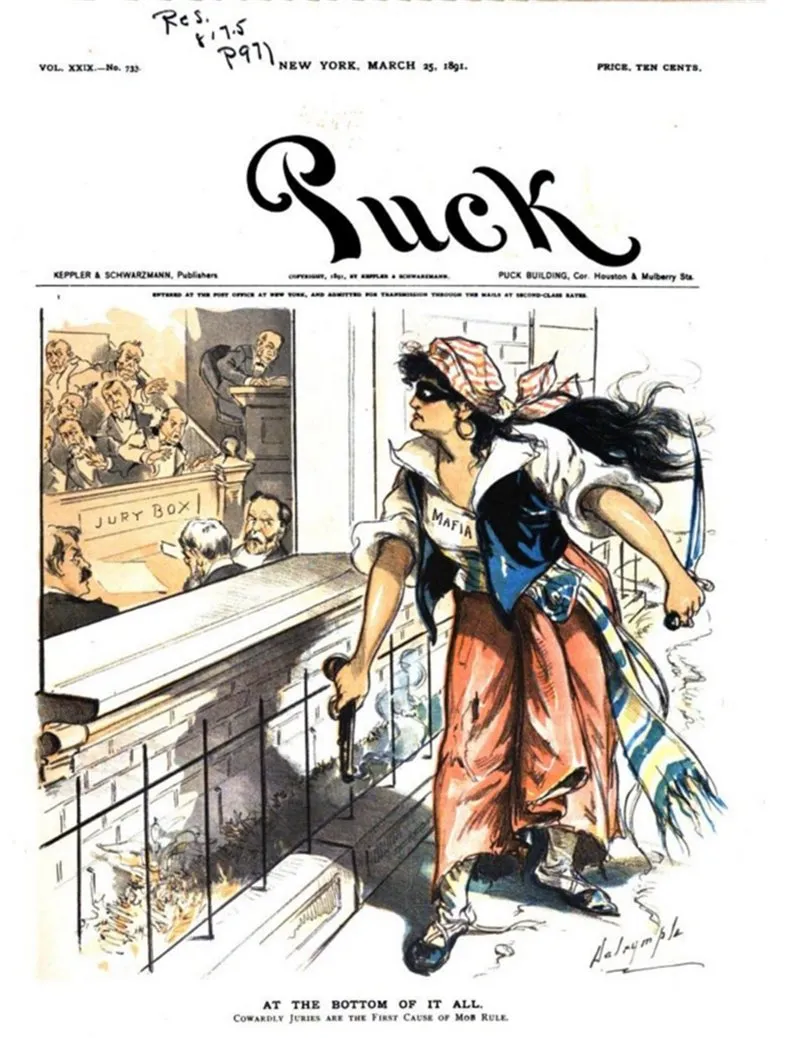

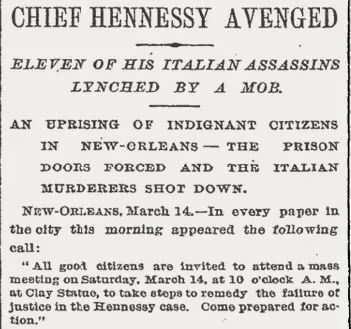

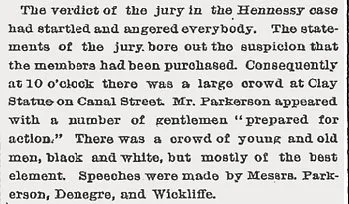

On March 13, 1891, the first trial of nine defendants took place. The jury exonerated six of them and dismissed charges against the other three. A wave of outrage swept across the United States—not just Louisiana and the South.

New Orleans had been gearing up for an anti-Italian convulsion and when it came, it was not by accident.

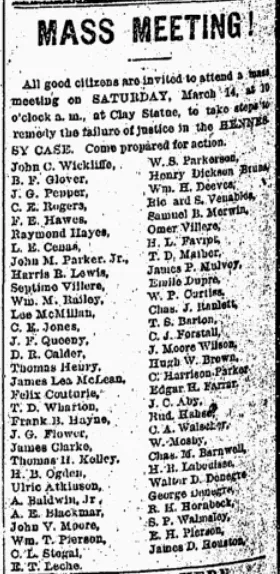

Puck Magazine blamed "Cowardly Juries", but the actual prime movers were the social, political and business leaders of New Orleans. They had a terrible program and did not hide in the shadows—proudly signing off on their call to violence in all the local papers.

This news echoed around the country, eliciting almost unanimous approval. The New York Times reprinted the "invitation to a lynching" in full, with all the signatories.

That is the short version anyway. In fact, nine reputed murderers were shot and two hanged. Meanwhile, seven others escaped in the confusion. None of them had been convicted of anything and some actually exonerated—thereby demonstrating the need for "action".

For the Times, "lynched by a mob" was no bad thing. "Mostly of the best element" might seem a nice flourish, but it was also accurate reporting, since the mob included many of the finest people in town.

Mayor Joseph Shakespeare hid from sight while his city exploded but that was all according to plan. When eventually tracked down at his club, he refused to acknowledge the bloody riot just outside.

The American press generally lauded the bold clean-up operation in New Orleans, but things looked distinctly different from the Italian side. No less an insider than Theodore Roosevelt, then serving on the United States Civil Service Commission, commented on a recent Washington dinner party in a letter to his sister:

"Monday we dined at the Camerons; various dago diplomats were present, all much wrought up by the lynchings of the Italians in New Orleans. Personally, I think it rather a good thing, and said so." (Theodore Roosevelt to Anna Roosevelt Cowles; March 21, 1891.)

The dinner took place on March 16, two days after the lynching, presumably in the home of James Donald Cameron (Senator from Pennsylvania and former Secretary of War during the Grant administration).

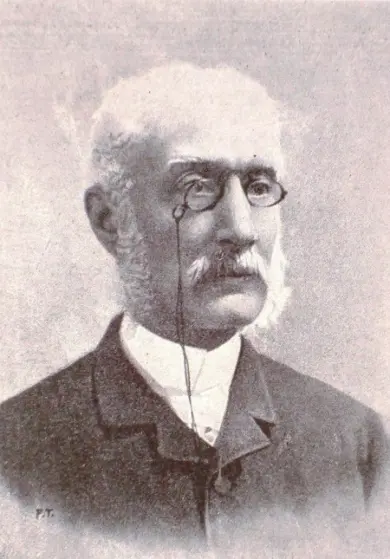

We would like to know the names of the wrought up dago diplomats and whether that included Italy's very grand Ambassador, Baron Francesco Saverio Fava. A Southerner himself (from Salerno), he and his family had long been fixtures at the former royal court in Naples.

The New Orleans lynching began as an Americn nativist uprising, but it soon morphed into a grave international incident. Four of the lynched men were Italian citizens, triggering a decisive test of will for the diplomatic corps of a relatively new country.

Fava knew the score better than anyone, having been sent by his government to establish their first permanent mission in Washington in 1881. He understood America well enough to realize that the New Orleans Massacre was not a one-off occurence.

In fact, at least 38 ethnic Italians were lynched in the United States between 1873 and 1916. Fava would have to cope wth a body-count of five in Tallulah, Louisiana, in 1899.

Telegrams were flying between New Orleans, Washington and Rome. At least some of the American newspapers lost their jingoist swagger, when they saw the story shift into another gear. They also found a compelling local protagonist in Pasquale Corte, the Italian Consul in that southern city.

In the wake of the Hennessy murder on October 15, 1890 and the mass lynching on March 14, 1891, Corte was an assiduous presence in and around the legal proceedings. On April 1, 1891, he testified at the ongoing Grand Jury investigation into the March 14 riot—which was cruising along as inconclusively as one might expect.

The eminent instigators of the mob were known to all—operating in the full light of day, with the press following close behind. But so what? In the words of the presiding magistrate, "Even if the Grand Jury were to indict the leaders of the lynchers, no jury could ever be secured to try them. Such publicity has been given to the affair that everyone is conversant with the facts of the case, and no one is without a fixed opinion."

While Consul Corte testified before the New Orleans Grand Jury, Ambassador Fava in Washington was already packing for his return to Rome—"recalled for consultation", as the saying goes. Corte would soon follow in his footsteps, lobbing a bomb on his way out the door.

Pasquale Corte was "level-headed and energetic", but also a keen strategist with a well-honed instinct for self-protection. In a twist worthy of a crime thriller, he prepared a searing exposé of political corruption and judicial malfeasance in New Orleans, revealing a cynical massacre and its cover up.

He left this account "in the hands of a friend, for use if necessary." When the Mayor banned him from the city, it was published in full in the New York Times on May 24, 1891. In their preliminary summary, the Times notes:

"Where the Consul speaks of politics in the letter he refers to the fact that all the leaders of the lynching party, as well as the Grand Jurymen, are members of the Young Men's Democratic Association, which, through an alliance with the Republicans, carried the last election, defeating the regular Democratic ticket and making Shakespeare Mayor, Villare Sheriff, and Luzenberg District Attorney."

If Corte waited a bit longer, he could also have cited the expropriation of Italian businesses by various signatories of the March 14, 1891 "Come prepared for action" appeal.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.