WHOSE COLUMBUS? WHOSE COLUMBUS DAY? Part 3: Italian Columbus Day vs. American Columbus Day

(3) ITALIAN COLUMBUS DAY vs. AMERICAN COLUMBUS DAY

And then came COLUMBUS DAY, America's official apology for the 1891 massacre...???

That is now the prevailing claim, but the historical evidence tells a different story.

In the wake of the New Orleans lynchings, the Kingdom of Italy broke off diplomatic relations for over a year—less for the killings themelves than the American government's failure to respond in a meaningful way.

Back in Rome, Baron Fava had his work cut out for him, explaining such arcane principles as "separation of powers" and "states' rights"—struggling to make sense of a great power's inabiity to act.

The stand-off between the two countries was not to anyone's advantage but there were limits to what President Harrison could deliver—for legal reasons and political ones too.

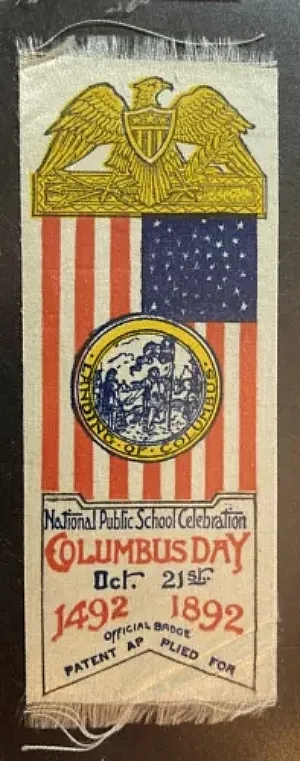

Eventually, Harrison elected to do the least possible. The United States would pay a total indemnity of $25,000 to the families of the eleven victims ($2,211.90 each.) The United States would declare a one-off Columbus Day holiday on 21 October, 1892 (not October 12).

Many like to see this as an empowering gesture to an abused immigrant community, but the evidence says otherwise. In fact, the holiday decree runs to 368 words, not one of which is "Italy" or "Italian" (nor "lynching" either).

From the Proclamation:

I, Benjamin Harrison, President of the United States of America...do hereby appoint Friday, October 21, 1892, the four hundredth anniversary of the discovery of America by Columbus, as a general holiday for the people of the United States...

Columbus stood in his age as the pioneer of progress and enlightenment. The system of universal education is in our age the most prominent and salutary feature of the spirit of enlightenment, and it is peculiarly appropriate that the schools be made by the people the center of the day's demonstration.

Let the national flag float over every schoolhouse in the country and the exercises be such as shall impress upon our youth the patriotic duties of American citizenship...

In the churches and in the other places of assembly of the people let there be expressions of gratitude to Divine Providence for the devout faith of the discoverer and for the divine care and guidance which has directed our history and so abundantly blessed our people.

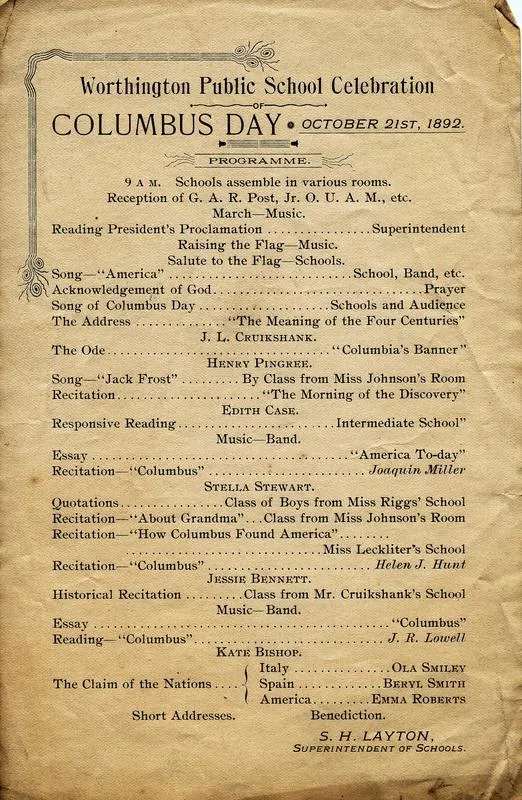

What did this bring into being—for example—in a small Ohio town, on October 21, 1892?

The Superintendent of Schools (grades 1 to 12) led off, channeling Benjamin Harrison's authority. To the assembled students and guests, he read the presidential proclamation. Then they raised the American flag, with a musical accompaniment. Then they saluted the flag. Then they sang America—and so on...

This was the first time that they—or anyone—performed the Salute to the Flag (better known as the Pledge of Allegiance). Shortly after 9am on October 21, 1892, some ten million school children, across various time zones, declamed it in unison, according to a strict protocol:

"At a signal from the Principal the pupils, in ordered ranks, hands to the side, face the Flag.

Another signal is given; every pupil gives the flag the military salute—right hand lifted, palm downward, to a line with the forehead and close to it.

Standing thus, all repeat together, slowly, 'I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands; one Nation indivisible, with Liberty and Justice for all.'

At the words, 'to my Flag,' the right hand is extended gracefully, palm upward, toward the Flag, and remains in this gesture till the end of the affirmation; whereupon all hands immediately drop to the side.

Then, still standing, as the instruments strike a chord, all will sing AMERICA—'My Country, 'tis of Thee.' "

"Not one school in America should be left out in this Celebration." Especially when the President of the United States gives it his imprimatur, a ready-to-use plan arrives in the mail and no kid wants to be "left out".

In fact, the Worthington Public Schools adopted the Youth's Companion template with only the slightest of variations, then extended its life with a souvenir program.

The National Celebration of Columbus Day was the brain-child of Reverend Francis Julius Bellamy—an all-Amercan mash-up of religious zeal, patriotic conviction and blatant hucksterism.

A Baptist minister from Upstate New York, he was imbued with the millennial enthusiasm of the Great Awakening. An economic populist, he gravitated to Christian Socialism, while remaining firmly committed to the separation of Church and State.

Bellamy was also a brilliant salesman, steeped in the culture of American boosterism. In 1891, the owner of the Youth's Companion—a Boston-based magazine that blanketed the entire country—hired him to ginger up their program of special offers.

That was a timely proposition, since the Reverend had just been expelled from his Boston pulpit due to his quasi-communistic views.

Bellamy's job was to sell flags, while continually stoking the demand for more.

In 1888, the Youth's Companion launched the Schoolhouse Flag Movement— a wildly successful scheme to solicit subscriptions by offering "free" American flags.

By 1892, some 26,000 of their banners were proudly waving across the country, but they sensed market saturation just around the corner.

So Bellamy cooked up the National Celebration of Columbus Day, which enshrined his new Salute to the Flag in American culture—while perpetuating the need for ever more flags.

What did any of this have to do with Italian prerogatives and Italian pride, in the face of lynching, economic exploitation and ethnic defamation?

Just about nothing, it would seem. If the Italians in America wanted to make their mark, they would have to do it themselves—with their own effort, money and connections.

When Bellamy's flag fest occurred on October 21 1892, it had already been upstaged nine days earlier—in many towns and cities—on the old accustomed date of October 12.

In terms of sheer pomp, the greatest national celebration took place in New York and filled six days, begnning with observances in local synagogues on Saturday October 8 and concluding with a banquet on Thursday October 13.

October 12, 1892 was the high point. That day began with a massive parade that surpassed even the great victory celebrations at the end of the Civil War.

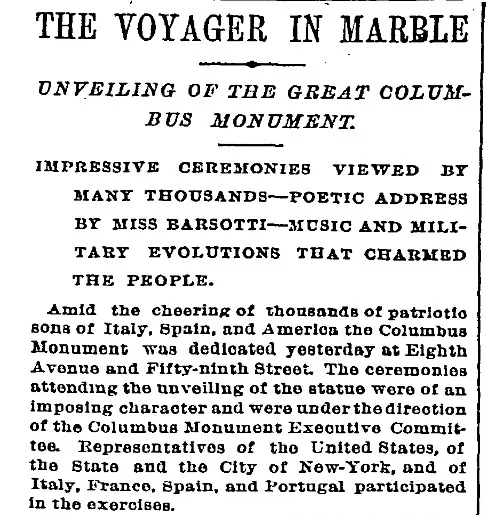

Then came the "Unveiling of the Great Columbus Monument" in a plaza bearing the explorer's name.

This was a thoroughly Italian occasion, no matter how many others were allowed a stake in the Columbus story. In fact, the monument was financed by private Italian donors across America, mobilized by the Columbus Monument Executive Committee. Carlo Barsotti—founder of the Progresso Italo-Americano newspaper (1879) and the Italian American Bank (1882) —was president of this committee.

The plan had been in the works for several years— long before the New Orleans lynchings. Carlo Barsotti announced it officially on July 6, 1890:

"The scheme of erecting and presenting this monument originated with the Italian merchants of New-York, and its details have been carried out in a manner that insures an artistic success.

'We are not going to give you an eye-sore," said banker Carlo Barsotti yesterday, 'such as those that now too frequently disfigure your streets and parks. About a year ago we began to raise the money, and then we asked the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs to appoint a commission of Italian artists and art authorities to select a design and a sculptor for us, and to oversee his work.'

'The Italian home Government entered heartily into our plan, and a commission was appointed that embodied the highest artistic sense of Italy.' "

The commission chose the Sicilian sculptor Gaetano Russo. His 76-foot tall creation—marble statue, granite column, granite pedestal and bronze fittings—was fabricated in Rome, then conveyed to New York on an Italian naval vessel.

Ambassador Francesco Saverio Fava returned from his diplomatic hiatus to do the chief honors— speaking exclusively in his native language, which was evidently understood by much of the crowd.

"Baron Fava, the Italian Minister, in an address that was frequently interrupted by cheers, formally presented the monument to the United States on behalf of the Italian Government."

A succession of notable personages took part, including General Luigi Palma di Cesnola, veteran of the Union Army and founding director of New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art. Annie Barsotti, Carlo's daughter, unveiled the statue—captivating the press and generally stealing the show.

The Times described Miss Barsotti as a "tall slender brunette":

"She was attired in the Columbus colors. Her dress was of white and orange silk, and over her broad-brimmed white hat drooped a plume of yellow and white ostrich feathers. In her gloved hand, she carried a bunch of yellow roses bound with red, white and blue ribbbons."

"Columbus Colors"? Is there any such thing? Those were actually the Papal Colors (post 1808)—which the Times reporters didn't know or chose to overlook.

Annie Barsotti was immediately preceded on the program by Michael Augustine Corrigan, Archbishop of New York.

On the previous evening, there had been a "parade of the Catholic societies", followed by a "Catholic celebration at Carnegie Music Hall" (which had opened a year earlier in 1891).

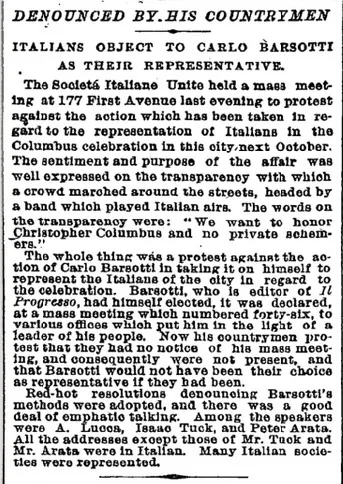

Annie Barsotti had many advantages on that occasion, being young, charming and not her father —who was loathed by a broad swathe of his compatriots in New York. Five months earlier, on May 25 1892, the Società Italiane Unite (United Italian Organizations) staged an evening parade countering Carlo Barsotti's take-over of the Columbus event:

"The sentiment and purpose of the affair was well expresed on the transparency with which a crowd marched around the streets, headed by a band which played Italian airs.

The words on the transparency were: 'We want to honor Christopher Columbus and no private schemers.'

The whole thing was a protest against the action of Carlo Barsotti in taking it on himself to represent the Italians of the city in regard to the Columbus celebration."

Since this was a night-time parade, the "transparency" was presumably a back-lit banner or screen. In regard to "scheming", Barsotti had himself elected at a secret gathering with only forty-six voters in attendence.

The protest march was followed by a mass meeting. "Red-hot resolutions regarding Barsotti's methods were adopted and there was a good deal of emphatic talking" almost exclusively in Italian. "Many Italian societies were represented."

Who were the hand-picked forty-six that voted Barsotti into office? Major contributors to the monument fund, we can imagine, men with money and influence.

Who were they not? Presumably any of the hundreds of thousands of impoverished Southerners who had poured into New York in recent years.

In regard to the high-profile Italians who spoke from the base of the Columbus Monument on October 12:

Carlo Barsotti, banker and publisher, was a Tuscan from Pisa.

General Luigi Palma di Cesnola, archeologist and diplomat, hailed from Rivarolo Canavese (near Turin) and was the second son of a count.

Ambassador Francesco Saverio Fava came from an old feudal family in Salerno (near Naples) and was a Baron himself.

The vast majority barely registered in the mainstream press, except when they stood up and protested. (Since Barsotti owned Il Progresso Italo-Americano, the largest-circulation foreign-language newspaper in New York, it would be interesting to see his own coverage.)

The Times acknowledged in passing the many società —mostly popular neighborhood associations, often closely tied to their places of origin in the Old Country:

"The Italian organizations whch had been drawn up in front of the stand marched and countermarched around the base of the statue and for a few minutes, a great hubbub of enthusiasm filled the air."

Then there were the musical groups, one of which led the anti-Barsotti demonstration while playing "Italian airs". At the climax of the unveiling:

"The moment the crowd caught sight of the figure of Columbus, it set up a mighty shout, and the bands poured forth the national hymn of Italy in unison."

How many bands were there at the Columbus Monument and who was playing? For generations in Italy, the banda civica, società musicale or associazione filarmonica has been a defining feature of local life. For immigrants in America, it took on an extra meaning—representing cultural continuity and ethnic pride, but also an essential right to make themselves heard.

The first-known Columbus Day observance took place in New York on the Third Centennial of the landing, October 12, 1792. It was organized by the Columbian Order, also known as the Society (or Sons) of St. Tammany and Tammany Hall—back when it was a nativist organization, not an Irish political machine.

The oldest public monument to the Navigator is the Columbus Obelisk in Baltimore, gift of the French Consul, presented also on October 12, 1792.

As Italian immigration picked up speed, more distinctly ethnic celebrations emerged. A crucial benchmark was the dedication of the Columbus Monument in Philadelphia on October 12, 1876 (at the time of the American Centennial).

Christopher Columbus then exploded on the national scene in 1892, marking the four-hundredth anniversary of his landing. The dedication of New York's Columbus Monument on October 12 was the most dramatic homage to Italy that the United States had ever seen.

Nine days later, on October 21, 1892, there was another massive parade—in Chicago. This converged on the site of the forthcoming World's Columbian Exposition, although the venue did not open until May 1, 1893.

Chicago had won this fair after an intense bidding war wtih New York City and the kick-off event was barely Italian at all.

The October 21 parade included "Italian Societies of 2,500 men" and the "Italian Democratic Club of 500 men, accompanied by a float of 'Columbus Discovering America.' ”

However, they were vastly outnumbered by Irish organizations, as well as Croatians, Germans, Greeks, Mexicans, Poles, Scots and Ulstermen.

The celebration—in fact—was Red, White and Blue American, coinciding with Francis Bellamy's National Celebration of Columbus Day on that same October 21. No one could miss the School House Flag Movement tie-in.

The reviewing stand, packed with dignitaries (including 31 state governors), was flanked by two sets of bleachers occupied by 2,500 children. They were dressed in the expected patriotic colors (one color for each child) and arranged to form a pair of enormous American flags.

The second of the two Columbus Days—October 21, 1892—came and went, amidst much to-do. Then the date ceased to matter, for all time.

Now, more than a century later, the October 12 holiday is still honored (and impugned) across the United States and in other "discovered" countries.

Behind all this, we find a historic clash of proclamations:

On June 19 1892, the United States Congress filed a joint resolution declaring a one-off October 21 holiday, which President Benjamin Harrison signed into law on July 21. They foresaw a distinctly American ritual in the public schools—nativist or assimilationist in tone—with a dose of generic Christianity thrown in:

"In the churches and in the other places of assembly of the people let there be expressions of gratitude to Divine Providence for the devout faith of the discoverer and for the divine care and guidance which has directed our history and so abundantly blessed our people."

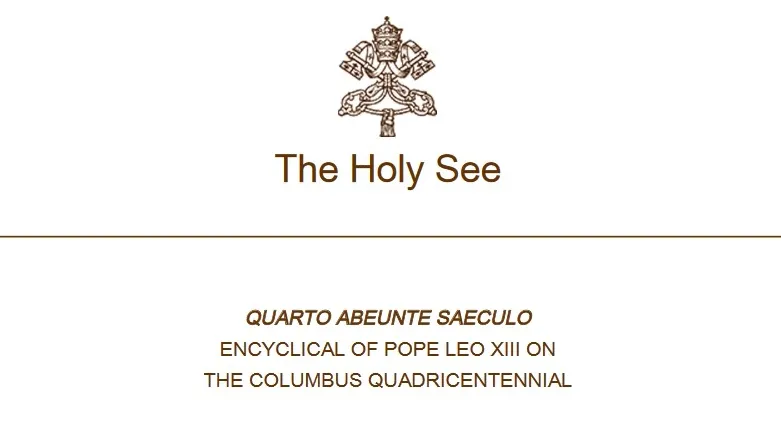

A few weeks later, "On the 16th day of July, 1892, in the fifteenth year of Our Pontificate", Pope Leo XIII issued the encyclical Quarto abeunte saeculo (The Fourth Century Having Passed), mandating an observance on October 12.

Unapologetically Catholic, the decree was addressed "To Our Venerable Brethren, the Archbishops and Bishops of Spain, Italy, and the two Americas". The crucial elements were Pontifical High Masses in the various cathedrals.

Rome, of course, had a prior claim to the “Devout Faith of the Discoverer”, which it was quick to assert —while pledging its gracious "assistance to the secular ceremonies" (which often had a Protestant cast in America).

Meanwhile, Leo XIII seemed to be hedging his bets on whether the holiday was intended only for October 12, 1892 —or annually, from then on, as desired by many faithful.

In fact, the Pontiff had good reason to avoid saying more then he meant regarding the homage due to the Great Navigator. Throughout the Nineteenth Century and up to the present day, petitions have been filed in the Vatican soliciting the canonization of Columbus as a Saint. Over the years, these were either tabled or rejected outright.

On October 12, 1892 celebrations occurred across America, in large towns and small, mostly of a Catholic character.

In Philadelphia, there were festivities in various Italian neighborhoods, but also city-wide events, including a torchlight procession of Catholic organizations on Broad Street, a Solemn Pontifical Mass in the Cathedral on Logan Square and a program by students from Catholic Schools at the Academy of Music.

October 12 had figured on the Philadelphia calendar since 1869, when the Societá di Unione e Fratellanza Italiana —a newly founded mutual aid society —held their first annual Columbus Day ball.

Celebrating the explorer was one of their defining activities and they played an essential role in commissioning the Columbus Monument, dedicated on October 12, 1876 at the Centennial Exposition.

Annually, until around 1920, Columbus Day processions made the long trek from South Philadelphia to the Monument in Fairmount Park (a total of six miles)—according to popular tradition, at least. Then more modern and less strenuous customs emerged.

In 1892, many could have told the Pope that October 12 observances were there to stay, in the United States at least.

Ten years earlier, the Knights of Columbus constituted their first chapter in New Haven. When the Fourth Centennial came around, they were ready to stage a parade in that Connecticut city with no less than 5,000 marching Knights.

At that time, Catholics were widely suspected of inherent disloyalty by native Protestants, so the organization forged a public bond with American patriotism, while enhancing the prestige of their own faith.

The Knights also had a more immediate goal— offering a Catholic alternative to the forbidden secret societies that were proliferating throughout America.

Their concern was very real. Nunzio Fanelli, the Philadelphian who who brought that city's Columbus statue into being, was buried with a Masonic rite in 1886.

At first, the Knights were mostly Irish but they soon reached out to a wider membership. In 1897, the San Salvador Council #283 began operation in the heart of Italian South Philly and is still active today.

In 1909, the national organization held its annual convention in Philadelphia. In a massive show of support, an estimated 5,000 turned out at the train station to welcome their next Sovereign Knight, the Philadelphia lawyer James Augustine Flaherty.

He held that position for 18 years (September 1, 1909-August 31, 1927.) It is said that Pope Pius XI referred to this influential layman as “the Bishop of the Knights of Columbus.”

In 1909, the Knights of Columbus filed a formal petition in Rome with the Sacred Congregation of Rites, leadng —they hoped —to the sainthood of their namesake.

This was spearheaded by Patrick John Ryan, Archibishop of Philadelphia and Senior American Archbishop. They were allowed to make their case but "too many weaknesses marred the life of Columbus for canonization to be possible".

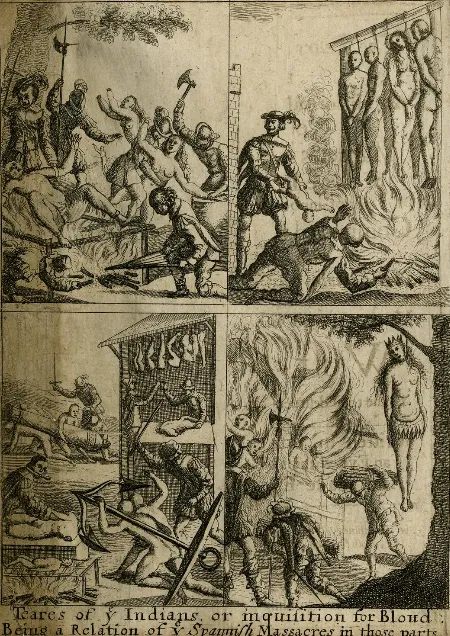

For a purported saint, Christopher Columbus' life was indeed problematic (leaving aside the extermination of indigenous peoples, which elicited little concern at that time).

First, there were his irregular marriages and illegitimate children. Then the lack of documented miracles (an essential quaification). Then unresolved questions regarding his place of birth (which impeded a full reconstruction of his earthly progress).

According to the Times:

"One thing only seems sure and that is that Columbus was an Italian. This is Italy's claim.

Spain argues that, as a saint, he should be callled Spanish, as had it not been for her he would have died in obscurity. This is Spain's claim.

America points out that he owes his lasting celebrity to the fact that America existed and that one only finds his cult there."

The Times edges into what the Congregation might call an argumentum ex nihilo (argument from nothing), proposing that Columbus was a de facto American and letting the rest go.

"That Monsignor Ryan, Dean of the American Archbishops, should have expressed the hope that the national hero would be made a saint has given a great fillip to the movement here."

In the wake of 1892, the Knights of Columbus lobbied governors and state legislatures across America to recognize the October 12 holiday, scoring their first win in Colorado in 1906, their second in New York in 1909 and then others in rapid succession. Meanwhile, there was intense politicking on the national level.

On April 30, 1934 Congress passed a joint resolution, which Franklin Delano Roosevelt enacted as law on September 23 1936, after a long delay. They reprised the general language of Benjamin Harrison's 1892 decree (but did not cite it as a precedent). They made Columbus Day a recurring annual event, while perpetuating the better-known —and implicitly Catholic—date of October 12.

Roosevelt let the Congressional Resolution sit for 29 months, then suddenly enacted it only 19 days before the first scheduled event. As a result, few knew that the festivity was on the books until the following year.

FDR then served as president until the spring of 1945, so he saw nine Columbus Days come and go. Year after year, he issued blandly patriotic holiday proclamations, leaving Italy and Italianness out of the mix—until 1942, when everyhing changed.

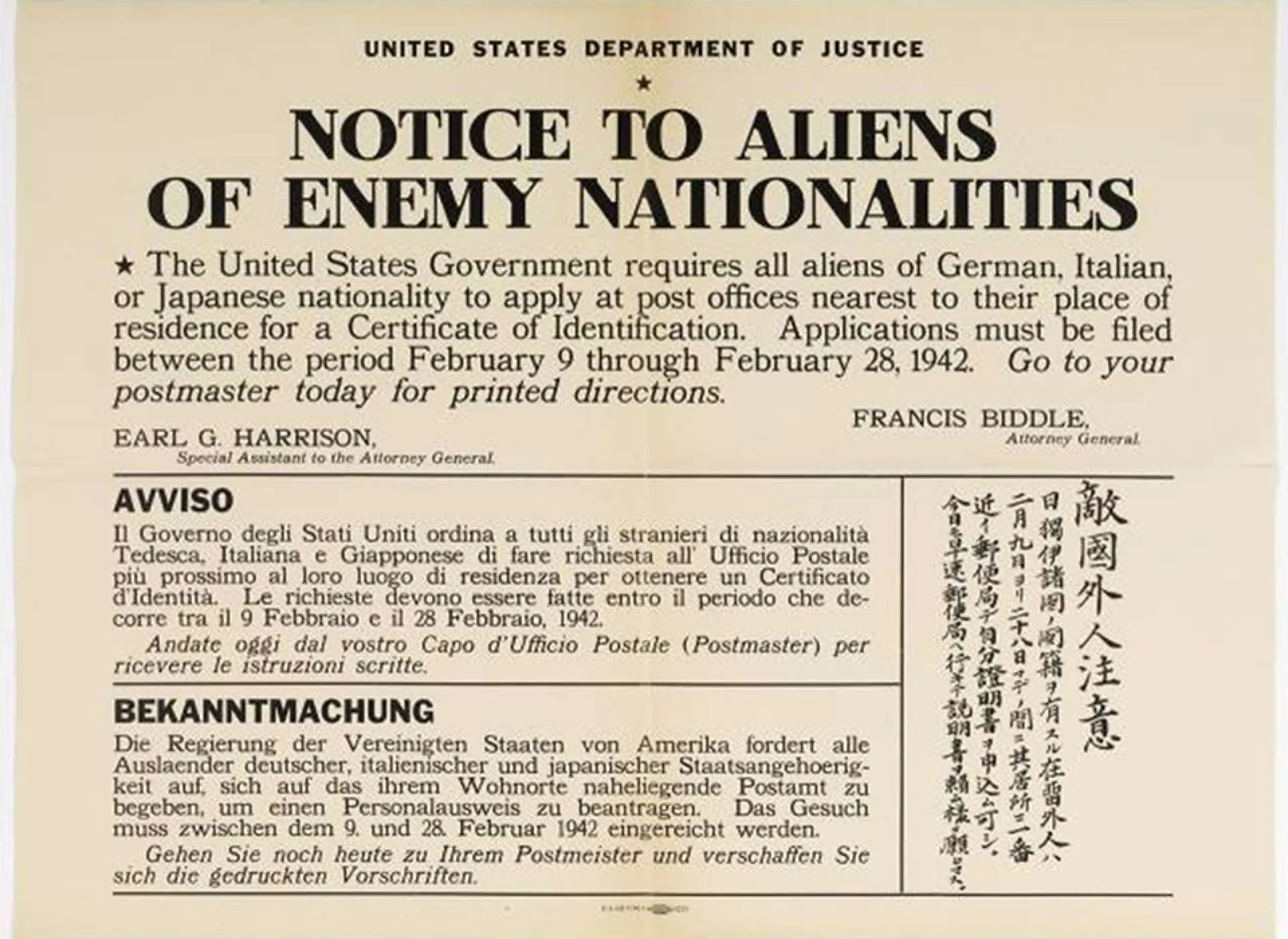

On December 11 1941— four days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor— Italy declared war on the United States, in solidarity with her Japanese allies.The American Government followed suit, declaring war on Italy that same day.

For Italian nationals living in America, there was an immediate price to pay. On December 8 1941 —one day after Pearl Harbor and three days before the declaration of war—President Roosevelt issued an executive order, designating as enemy aliens "all natives, citizens, denizens or subjects of Italy being of the age of fourteen years and upwards who shall be within the United States...and not actually naturalized".

On February 9, 1942, Italian (also German and Japanese) foreign nationals were called to register at their local post office. In the months that followed, the Department of Justice arrested and then released 1,881 Italians but interned 418 others. (The figures vary in different sources.)

These were only a few of the six million Americans of Italian origin, while Japanese on the West Coast were facing far worse. Still, the Italian sanction was a legal, moral and political nightmare for the Roosevelt administration —which they sought to undo as quickly and as publicly as possible.

Attorney General Francis Biddle —whose name was all over the registration and internment débacle —secured a prime slot for himself in the middle of a gala Columbus Day event at Carnegie Hall:

"The meeting at which Mr. Biddle spoke was a concert celebration arranged by Mayor [Fiorello] La Guardia with the cooperation of Local 802 of the American Federation of Musicians and the Philharmonic Symphony Society of New York."

Not for nothing was the Mayor of New York Italian-American and many of the musicians too.

Biddle's address was momentous, to say the least. He rolled back his own discriminatory orders, then lauded Italian history, character and culture.

The Times covered this event exhaustively and published his very long speech, inserting these succinct headings:

"Italy's History Recalled / Recalls Garibaldi's Stand / Leopardi is Quoted / Mussolini is Assailed / Revolt Against Fascism On / Would Lift Literacy Test / Hints Aid for Others".

While Italian Americans were Americans in full, the Mussolini regime had alienated them from their spiritual homeland:

"No people knows as well the meaning of a liberated land. None feels the longing as terribly, as the nation which has had it and lost it. There are among you many men and women who have loved what once was Italy. There are those who call that older Italy their own."

Biddle waxed poetic— quoting Dante on the subject of exile— while offering concrete updates on relevant administrative matters.

"His address was carried over a nationwide radio hook-up of the Mutual Broadcasting System."

President Roosevelt was burning up the radio waves as well. That evening, he concluded his Fireside Chat (number 23, usually titled On the Home Front), with a brief note:

"We are celebrating today the exploit of a bold and adventurous Italian—Christopher Columbus—who with the aid of Spain opened up a new world where freedom and tolerance and respect for human rights and dignity provided an asylum for the oppressed of the old world."

At long last, Christopher Columbus was explicitly "Italian" but there was more. FDR prefaced this same Fireside Chat with an eloquent reflection on the 450th Anniversary of the Discovery of America.

This presidential addresss rolls on for another five paragraphs. Roosevelt assures his listeners that Columbus exemplifies the essential American goals of "liberty, democracy, religious tolerance, the fuller life", which was then threatened by a cataclysmic war.

Between July 1942 and May 1945, Mayor La Guardia beemed some 150 weekly radio broadcasts into Italy—in Italian—by way of shortwave radio. He offered a counter-narrative to Fascist propaganda during a challenging time, from the landing of American troops in Sicily, through the fall of Mussolini, Italy's surrender to the Allies and the German occupation.

By Columbus Day 1944, Italy was an occupied and embattled country, not an adversarial one. In a show of support and reconciliation, Mayor La Guardia led that day's parade down Fifth Avenue.

During the war, an estimated one million Italian-Americans served in the armed forces, roughly ten percent of the total enlistment. Now, the flags of the two countries were flying side-by -side.

As they emerged from the brief but traumatic 1942 crackdown, Italian-Americans relearned an old lesson: Christopher Columbus was the key to their essential Americanism, guaranteeing their place in the life of the nation.

Year after year, his celebration grew by leaps and bounds. On June 28 1968, Lyndon Johnson signed a national law enshrining it as a Federal Holiday. Beginning in 1971, all government offices would be closed on the second Monday in October— October 12, more or less.

Then 1992 came around —barely thirty years later —the five-hundredth anniversary of an increasingly contested "discovery". With breathtaking suddenness, Cristoforo Colombo / Cristóbal Colón / Christopher Columbus developed a split personality—as both an Italian cultural hero and the archvillain of a burgeoning anti-colonialist movement.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.