Jews and Magic in Medici Florence:

The Secret World of Benedetto Blanis

CHAPTER ONE: THE PIAZZA

You are standing in the middle of downtown Florence in the vast and vacant Piazza della Repubblica, an echoing no-man’s-land bordered by oversized cafès, tourist shops and five-star hotels. There is hustle and bustle of a kind, but not the hustle and bustle of locals doing real things in the course of a real day. Tour groups shuffle from museum to church to museum, with the aimless aggressiveness of their sort. Taxis come and go, horns blaring, plowing through this supposedly pedestrianized zone.

Over the rooftops, just offstage, loom the towers and cupolas of the city of Florence—right there where they are supposed to be, all the familiar postcards from the land of the Renaissance. A few hundred steps in one direction would take you to the red-domed cathedral, a few hundred steps in another to the castellated town hall. But here in Piazza della Repubblica there is another story to tell, as inscribed on the ponderous triumphal arch at the back of the square:

L’ANTICO CENTRO DELLA CITTÀ

DA SECOLARE SQUALLORE

A VITA NUOVA RESTITUITO

MDCCCXCV

THE ANCIENT CENTER OF THE CITY

RESTORED TO NEW LIFE

FROM AGE-OLD SQUALOR.

1895

So, urban renewal struck with a vengeance and the ensuing century scarcely softened the shock of impact. But what ancient center? What former squalor? What alleged new life?

For many generations, in fact, another inscription surmounted another portal near this same site:

COSMUS MED. MAG. ETRURIAE DUX

ET SERENISS. PRINCEPS F. SUMMAE IN OMNES

PIETATIS ERGO HOC IN LOCO HEBRAEOS

A CHRISTIANORUM

COETU SEGREGATOS NON AUTEM EIECTOS VOLVERUNT

BONORUM EXEMPLO DOMANDAS FACIEE

ET IPSI POSSINT

ANNO D. M. DLXXI

AND HIS SON THE MOST SERENE PRINCE FRANCESCO

MOTIVATED IN ALL THINGS BY GREAT PIETY

WILLED THAT THE JEWS BE ENCLOSED IN THIS PLACE

SEGREGATED FROM THE CHRISTIANS BUT NOT EXPELLED

SO THAT THROUGH GOOD EXAMPLE THEY MIGHT COME

TO BOW THEIR STUBBORN NECKS TO CHRIST’S LIGHT YOKE.

YEAR OF THE LORD 1571

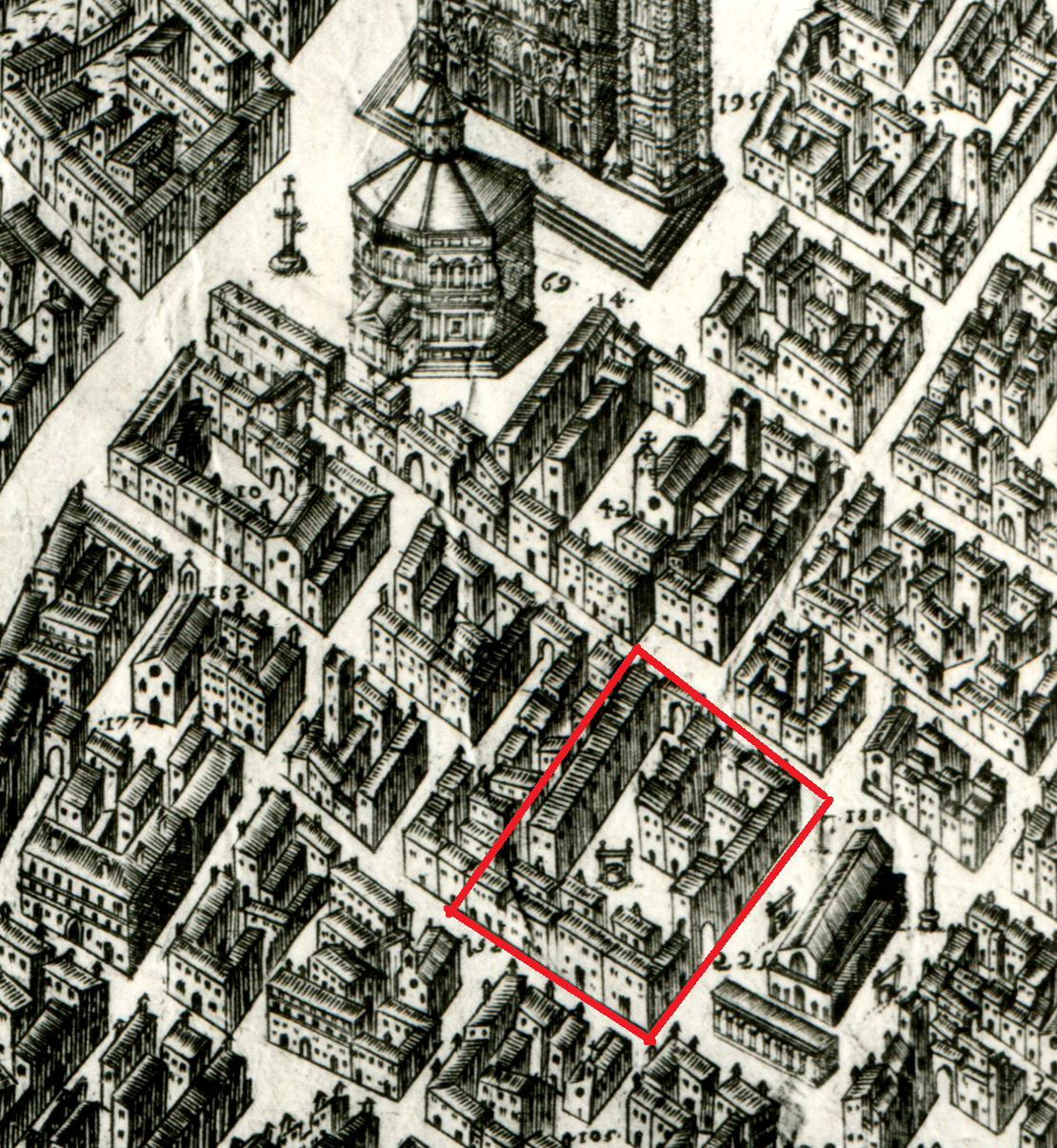

Cities are defined as much by what is missing as by what is present. Two thousand years ago in this very place, there was the forum of the Roman colony of Florentia. Then from the Middle Ages until nearly the present day, the Mercato Vecchio, Florence’s central market. And on the edge of this market, the Jewish Ghetto, as decreed by the Medici Grand Dukes of Tuscany.

Scant traces ofthe Roman forum remain below ground. The central market has since moved twice, first to nearby San Lorenzo and then to distant Novoli. The Jewish Ghetto ceased to exist as a physical place more than a hundred years ago, when its buildings were razed in the late nineteenth century. It survives, however, as an historical fact and perhaps even as a state of mind.

Rather than brick and stone, the primary evidence for the Florentine Ghetto now consists of words on paper, preserved for centuries in local archives—usually Christian archives, not those of the Jews themselves. For years, the leaders of the Jewish community periodically obliterated their own history, clearing out the old documents on their shelves to make space for new ones. If we want to discover the Ghetto as it was and trace the lives of its inhabitants, the place to begin is the vast Medici Granducal Archive with its police files, judicial records, legal contracts, government deliberations and millions of letters.

Sometimes there is an extraordinary trove waiting to be found—words on paper that seem to cancel the intervening centuries and bring us face to face with the past. Between 1615 and 1620, for example, Benedetto Blanis (c.1580-c.1647), a Jewish scholar and businessman in the Florentine Ghetto, wrote 187 letters to Don Giovanni de’ Medici (1567-1621), an influential member of the Tuscan ruling family. Benedetto served Don Giovanni as librarian—managing his palace library, organizing and cataloguing its contents, acquiring books from various sources and sharing his patron’s most recondite interests.Together they ventured into dangerous and often heretical fields of enquiry—astrology, alchemy, Kabbalah and beyond.

In Benedetto’s letters, we see him living life on the edge, cultivating risks for their own sake in a strange no-man’s-land between the Ghetto and the Medici Court. He was a scholar by choice but a businessman by necessity and his commercial ventures, especially loan-sharking and debt-collection, made him many enemies. Benedetto’s worst foes were other Jews and the very worst his own in-laws and cousins—recent converts to Catholicism.

.webp)

Benedetto played his most daring games of brinksmanship in the realm of the occult, trusting blindly in his patron’s power and influence. He traded in esoteric writings, especially works on the Inquisition’s Index of Prohibited Books and he was incarcerated twice, first for two weeks and then for several years. After one particularly stormy encounter with Monsignor Cornelio Priatoni, the Father Inquisitor in Florence, Benedetto Blanis reported to Don Giovanni de’Medici, “I was a bad Jew, he said, because I went from one condition to another and did not stay Jewish. That, he said, was his definition of a bad Jew.”

Benedetto may have been a good Jew or he may have been a bad one, but he was undeniably a gifted and provocative individual. Thanks to his personal letters and a host of otherdocuments in the Medici Granducal Archive, we can follow him closely, day by day, as he struggled to make a life for himself against daunting odds.

%20-%202.webp)