Live on Stage!

FLORENCE. CARNIVAL. 1614.

Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger conceived L’Ebreo/The Jew for the Carnival of 1614 at the Medici Court. We know that from the evidence of the script . But what did this conjunction of time and place mean in concrete terms?

According to custom, celebrations ramped up to a frenetic conclusion in the last days of the holiday cycle—between February 6, 1614 (Berlingaccio or Fat Thursday) and February 11, 1614 (Martedì Grasso or Fat Tuesday). Then on February 12, 1614 came Ash Wednesday and the prot racted gloom of Lent, followed by Holy Week and eventually Easter (March 30, 1614).

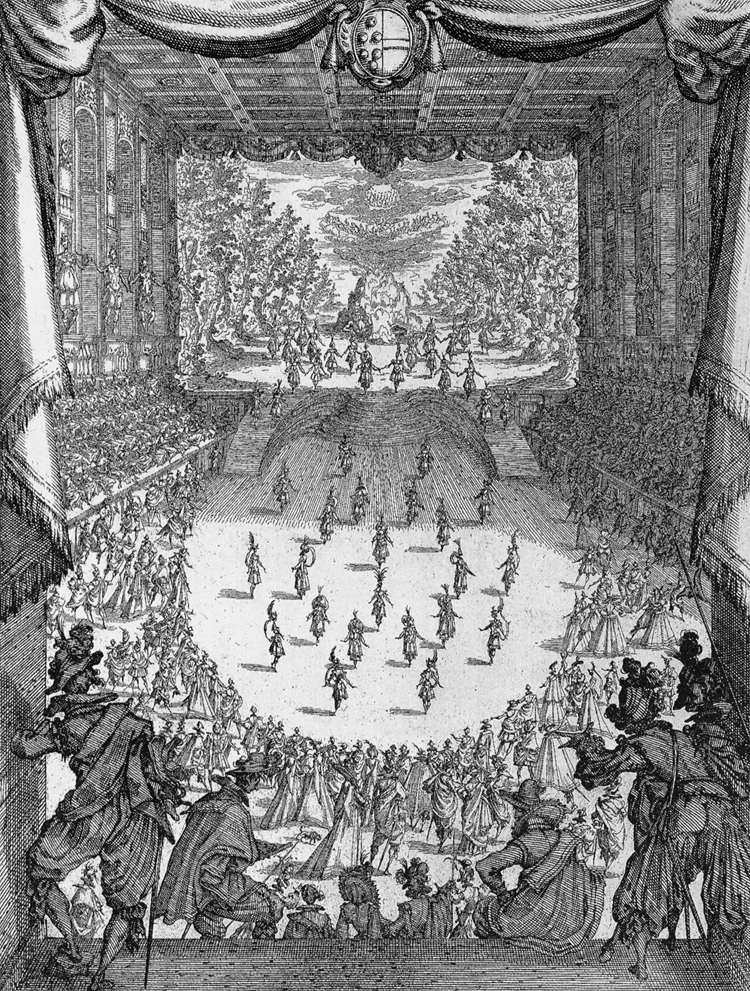

In Florence, Carnival was the annual theater season, with a rush of public and private performances of every kind. At the Medici Court, there was at least one spectacular production—with lavish costumes, fantastic sets, dazzling special effects, massed singers and musicians, plus elaborate dance routines. Usually, this took place at the great theater in the Uffizi Palace or else ingenious temporary structures in nearby piazzas or gardens.

Then there were private entertainments—less stately but often more amusing—hosted by various members of the Medici family, their courtiers and other patrons in palaces across the city. These ranged from literary dramas to light-hearted comedies to masked balls to musical reviews. Meanwhile, free-wheeling performances popped up more or less everywhere—in taverns, clubs and on street-corner stages, presented by traveling troupes of professional actors or local amateurs.

Where did Michelangelo the Younger’s L’Ebreo/The Jew fit into this picture? With its Jewish theme, frequent descent into lowbrow comedy and prevailing lack of “spectacle”, we cannot imagine it as a full-dress production at the Uffizi Theater. The Medici Court, however, was notaby expansive, encompassing the full hierarchy of the Grand Ducal regime and the upper echelons of their capital city. We can easily see L’Ebreo/The Jew in a great salone in the residence of a younger son or nephew of the ruling family, or else a rich and privileged courtier.

Grand marriages were often celebrated during Carnival, since the festive license of the season facilitated the presence of Medici princes at such events. Comedies of the time normally end with a marriage or at least a formal engagement. L’Ebreo/TheJew concludes with a double betrothal, followed by a pseudo-stately procession of the play’s characters—evidently leading real guests to a celebratory feast. This, in any case, is the setting that I most easily envision

LIVE. ONSTAGE. TODAY.

Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger abandoned L’Ebreo/The Jew—his most original and intriguing Carnival comedy—as a chaotic-work-in-progress. I describe the very rough draft that he left us and the challenges it presents, in the introduction to my transcription here on this website.

At this time, I am offering an original performance script, based on Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger’s own draft of L’Ebreo/The Jew. My adaptation—in English—represents only one of the directions in which I could have taken Michelangelo the Younger’s rough-quarry of dialogue, stage instructions, to-do-lists and notes-to-self, not to mention second thoughts and frantic rewrites.

My present adaptation was shaped by a specific set of circumstances. Friends in Washington, DC heard about my discovery of L’Ebreo and expressed their interest in performing it as a staged reading. My initial reaction was, “Nice idea, but...” How on earth was I going to take it from a fragmentary and often barely legible draft in quirky seventeenth-century Florentine to a viable performance piece in present-day English?

Then came a sudden realization, which turned me from doubter to enthusiast. I saw a unique opportunity to follow in Michelangelo the Younger’s footsteps as a dramatist, discovering—in practical stage terms—what was really going on in those much-belabored pages. It also occurred to me—somewhere along the way—that this could be fun!

I might have gotten lost if I did not have strict guidelines to keep me on track. I needed to limit myself to eleven characters—the exact size of the company—down from Buonarroti’s seventeen. Since I was developing a staged reading, I had to imply or describe—not show—most of the physical action. The same, as well, with stage sets and scene changes.

Oddly enough, this revamping would have been easier to achieve with one of Buonarroti’s more static and literary plays, with long speeches and elegant word play. L’Ebreo, however, was an odd and somewhat uncharacteristic excursion into the Commedia dell’arte mode, with sight gags and a good deal of physical comedy. How was I going to manage that with everyone just sitting down and standing up, while holding scripts?!

So, I combined a few characters (a notable improvement, since the many I had were getting in each other’s way). I empowered an underused character—the neighborhood busybody—and made her into an onstage narrator. With great regret, I cut the three comic policemen—Keystone Kops in slapstick style. I would, however, love to bring them back!

Tell me what you think! As I said, there is much that I could have done differently while remaining true to the spirit of Michelangelo the Younger’s L’Ebreo / The Jew. You are welcome to use my performance script—for free—however you wish. Indeed, I would be glad to send you a more user-friendly version of the text, which you can print out and mark up as needed. And if you would like to develop the production in other ways—let’s talk!